by Chris Horner

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness, assuming it makes a showing at all. This can lead people to reject the idea of engaging with them before they’ve even had time to discover the ideas or experiences they might have learned from or enjoyed. Clearly, not everything will be to everyone’s taste, but you can’t know until you give it, or them, a try.

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness, assuming it makes a showing at all. This can lead people to reject the idea of engaging with them before they’ve even had time to discover the ideas or experiences they might have learned from or enjoyed. Clearly, not everything will be to everyone’s taste, but you can’t know until you give it, or them, a try.

What makes this problematic is that it is the least credible – and creditable – things that they have supposedly said or did that hang round them like a bad smell: Nietzsche the proto facist, Freud the sex mad coke addict, Marx the totalitarian etc. Popular beliefs about many of the key figures of modernity are often seriously askew, and sometimes at 180′ from the truth: Nietzsche was neither anti Semitic, nor a nationalist; Freud didn’t say it was ‘all about sex’; Marx wasn’t a proponent of a one party state, etc. It is almost as if whatever the popular view is of these figures, the truth lies in the opposite direction. So my instinct is to try to put the record straight. But what to do when the popular idea of an artist or thinker actually does correspond to something real – something true and bad?

Take Richard Wagner as a classic example. Read more »

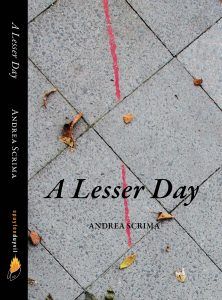

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.