by Mark Harvey

Most people don’t want to hear your sob stories, even if they pretend to be caring listeners. Even a good friend listening to your personal version of Orpheus and Eurydice—and making all the right noises—is probably focused on whether to put snow tires on their car Thursday or Friday.

Some of us turn to music to ease our mortal wounds and it’s a bit of a mystery as to why sad music is actually helpful. I turn to either classical or country music when I need to feel better about a loss or when things just won’t go my way. There is a vast distance between the ultra-cultured notes of, say, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and the decidedly baseborn lyrics of the country songsters I like. But lo and behold, each can have its healing powers, and a little of each might be the key to a good diet.

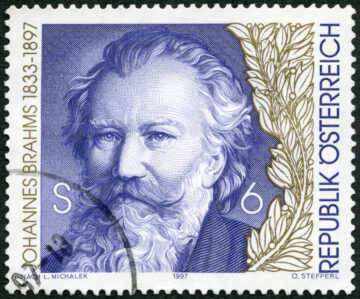

You can hear the grand wounds and the bending of the Weltgeist in classical music and it often involves losing a village or watching Napoleon fail at taking Russia. The great composers endeavor to capture tidal movements and tidal emotions. They have a whole orchestra with bizarre instruments such as glockenspiels and contrabassoons, to accompany the more common violins and pianos. To play in a great orchestra takes merely 15 years of daily practice from the age of four along with some otherworldly talent. So if you wake up feeling sad about the fall of democracy in Europe, by all means, reach for your Schubert or your Brahms. That’s what it takes to handle the bigger themes.

Country music is less ambitious and more concerned with things like, “Whose bed have your boots been under? And whose heart did you steal I wonder?”. But when you’re in the throes of a tawdry breakup, the clever, brassy lyrics of a Shania Twain or a Jamie Richards might offer the fast, powerful relief you need and can’t get from the refined classical music.

Good country music has the boomy-bassy-twangy sound made by simple instruments such as slide guitars, fiddles, and banjos. It can be plaintive and crooning but part of what makes it successful are clever, ironic lyrics. Read more »

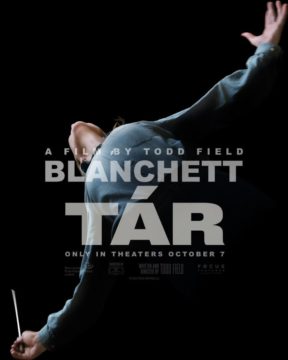

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).  This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.

This is the kind of novel which when read makes you wonder why it isn’t better known and more widely celebrated. The late 19th century saw a wave of plays and novels dealing with ‘the New Woman’ – the educated, worryingly independent, vote-seeking, bicycling women of the late Victorian/Edwardian age. Examples include Victoria Cross’s Anna Lombard (1901), Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) Many of these were predictable rubbish: marriage or death solves everything. Exceptions among plays are Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession, and among novels HG Wells’ Ann Veronica (1909), but it’s the Gissing that is really the winner among novels. Gissing avoids most of the cliches and stereotypes and produces a narrative that is genuinely absorbing and a set of themes and characters one remembers long after the book is put down. Gissing is an odd fish: he has real empathy for the plight of the poor and the rejected (both here and in The Nether World and his more famous New Grub Street), but has an ‘official’ conservative ideology which, when he lets it, blocks him from being able to imagine how the agency of working class or (as here) mainly lower middle class women might work for their liberation. In this he isn’t alone: many great novelists have said more through their literature than their ‘official’ beliefs ought to allow them to do (think of Dostoyevsky) In The Odd Women, he largely lets his imagination take him places his philosophy could never encompass. The book emerges as a fascinating account of the situation of the ‘superfluous’ women of the 1890s – and shows how they either succumbed to or overcame the world that seemed to have no place for them.