by Brooks Riley

I didn’t plan to write about Caspar David Friedrich for his 250th birthday. He belongs to a different time in my life and a different aesthetic pathology. But as the date edged closer, I found myself missing that impossible reach for the sublime that his work had once provoked in me.

I cannot not write about him.

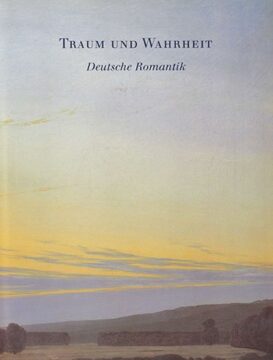

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

Later, it was the darkness that would keep me going back to his work.

Caspar David Friedrich loved the dark. He loved it so much that he got married at 6 am on a cold January morning, long before a Dresden sunrise. He often went out for walks along the Elbe at dawn or at dusk and lurked in the twilights or the moonlights, bringing home threads of illuminated thinking one can only have at night in the dark. I understand him. Darkness, with its tendency to distort as well as to obscure, is conducive to thinking in unlikely ways, offering a different kind of clarity that is difficult to achieve in daylight, when the light interferes demanding attention. Read more »