by Brooks Riley

I didn’t plan to write about Caspar David Friedrich for his 250th birthday. He belongs to a different time in my life and a different aesthetic pathology. But as the date edged closer, I found myself missing that impossible reach for the sublime that his work had once provoked in me.

I cannot not write about him.

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

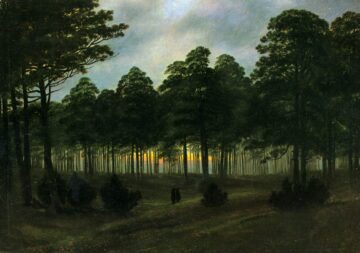

Later, it was the darkness that would keep me going back to his work.

Caspar David Friedrich loved the dark. He loved it so much that he got married at 6 am on a cold January morning, long before a Dresden sunrise. He often went out for walks along the Elbe at dawn or at dusk and lurked in the twilights or the moonlights, bringing home threads of illuminated thinking one can only have at night in the dark. I understand him. Darkness, with its tendency to distort as well as to obscure, is conducive to thinking in unlikely ways, offering a different kind of clarity that is difficult to achieve in daylight, when the light interferes demanding attention.

He loved the outer edges of the day when the light was at its most unpredictable—but not the noonday sun with its steady blast of klieg-light overexposure. (His series on times of day includes an overcast midday—confirming my suspicion he would do anything to avoid painting high noon on a clear day.)

For a painter who came to embody German Romanticism, Friedrich was surprisingly sober and unromantic—a biedermeier Pomeranian Lutheran who married late and raised three children without letting them change his set and solitary ways. With the possible exception of Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, there was nothing vain or Byronic in his character. No impulsive behavior or wild excesses. No trips to Italy. He didn’t belong to that lively rebel group of Jena poets and thinkers who were busy fomenting the movement called Romanticism. He did have friends, most of them fellow painters, and is said to have had a good sense of humor, in spite of periodic bouts of depression.

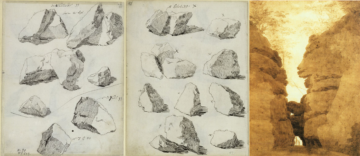

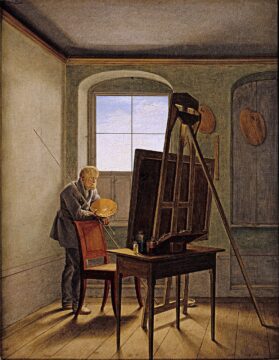

Even after finishing his studies in Copenhagen, he didn’t paint in oil until he was nearly thirty. Instead, he wandered and sketched for years, honing his craft to build a collection of vistas, trees, and boulders the way a location scout for a movie might do. Back in his atelier, (a spare room with an easel by the window) he would eventually delve into this reserve—to forge the landscapes of his imagination in oil.

Even after finishing his studies in Copenhagen, he didn’t paint in oil until he was nearly thirty. Instead, he wandered and sketched for years, honing his craft to build a collection of vistas, trees, and boulders the way a location scout for a movie might do. Back in his atelier, (a spare room with an easel by the window) he would eventually delve into this reserve—to forge the landscapes of his imagination in oil.

That window says it all: The lower half is shuttered to block the view. All Friedrich needed was the light by which to paint. The rest came from within. “A picture must not be invented but felt.”

He wasn’t after verisimilitude, even when he approximated existing landscapes. He was after the empowering essence of nature and the mercurial atmosphere that went with it—akin to bottling a magical time of day or preserving a ghostly moment between the pages of an album. He could make a landscape breathe in and out. You didn’t just see the damp rising from the earth, you could smell it, or feel the cool evergreen mist settling down between the trees at dusk.

Many of his paintings are the expressions of a secular sublime, that very expansive dimension of feeling and belonging that is the promise of Romanticism—especially now, if only as a distant echo, in an era when nature in its purest form is endangered or irrevocably altered.

Some early Friedrich paintings are cringeworthy by today’s standards, with religious emblems superimposed on his wild and pagan natural world—as tasteless as a billboard for god in Yosemite. Crucifixes like stickers atop rocky precipices are the kind of kitsch that reminds me of Dürer’s praying hands. It wasn’t Dürer’s fault that those hands went viral, he was simply sketching them for use in a painting where they would have gone unnoticed. But for a time, Friedrich was definitely guilty of desecrating the very essence of that natural universe he so meticulously crafted. Fortunately, he abandoned the habit early on, but for an occasional church ruin or abandoned cemetery.

Dropping those crosses made way for the staffage and Rückenfiguren (figures viewed from the back) that humanize his work. The scale is often off the charts—the tiny shepherd and his flock against the vastness of the extending mountains in Morning in the Mountains. But it doesn’t matter. That shepherd is our connection to this wilderness, just as those two men watching the sunset are our guides to Friedrich’s umbrous shoreline.

We are all one and the same, whether dwarfed by the surroundings or prominent in the foreground; we take up these roles as observers—all facing in the same direction as the Rückenfiguren. This may explain the explosive popularity of Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, which allows us to become that figure looking out over the foggy terrain—in a metaphor of our own choosing.

Friedrich changed the course of art history with his Rückenfiguren. In Florian Illies’s lovely book, Zauber der Stille (The Magic of Silence), he somewhat overstates the case that Friedrich used figures seen from the back because he was bad at painting faces. I prefer to think that he wasn’t interested in faces—which puts him at odds with the long history of art, which has nearly always included faces where human figures are featured.

His lack of interest in faces was not misanthropic. He often anchored those hybrid landscapes to the people gazing at them. He understood that the ambiguity of the Rückenfigur was more potent than the depiction of awe and wonder on a face. He kept our eyes on the ball by having us pay attention to what his Rückenfiguren were looking at.*

Some of his work borders on the abstract—views of the sky that completely ignore the ground below.

Or The Monk by the Sea—not a monk at all but Friedrich himself facing the roiling fogbank headed his way across the water—a darkly prophetic painting that broke the rules and laid bare his existential angst. It’s also a personal declaration: “I have to surrender myself to what encircles me, I have to merge with my clouds and rocks in order to be what I am. Solitude is indispensable for my dialogue with nature.”

Goethe, an early fan, didn’t get this painting, and even made fun of it. The one who bought it, the 14-year-old Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, fell in love with it.

Goethe, an early fan, didn’t get this painting, and even made fun of it. The one who bought it, the 14-year-old Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, fell in love with it.

My personal favorites change from year to year—or from hour to hour, depending on my mood:

—The Sea of Ice

I once wrote: “I am certain that he saw the end coming—recognizing the awful beauty in destruction. . . All that’s left of us is a shipwreck, dwarfed by massive colliding slabs of ice. How prophetic he was.”

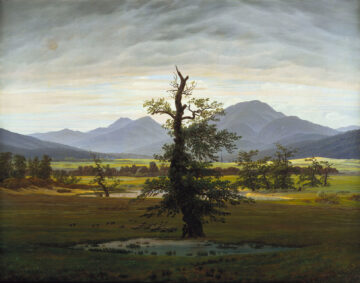

—The Lonely Tree

The perfect ratio of man to nature in this gorgeous landscape.

—Evening on the Baltic Sea

A rare example of figures seen from the front—two men warming themselves in front of a fire, one of them smoking. Friedrich’s mastery of light is on full display here.

—View of Arkona with Moon Rising

This pencil and sepia ink drawing from 1803 makes me want to put on sunglasses even though it’s just a paper moon.

Friedrich became a star during his lifetime but fell into obscurity and poverty long before his life was over. A stroke ended his career five years before his death in 1840. More than sixty years would go by before he was rediscovered by the Norwegian art historian Andreas Aubert at the turn of the 20th century. Later, the Nazis would misappropriate Friedrich for their cultural agenda. It was only in the seventies that he began to be resurrected from a complicated legacy. The current exhibitions around his big birthday will finally confirm his rightful role as a paragon of German Romanticism.

Friedrich seemed to flirt with that possibility: “I am not so weak as to submit to the demands of the age when they go against my convictions. I spin a cocoon around myself; let others do the same. I shall leave it to time to show what will come of it: a brilliant butterfly or maggot.”

Welcome, butterfly.

*****

* I could always guess what my two cats were thinking when I saw them from behind. It was their body language. Unlike Friedrich, I do have trouble drawing. But I was lucky enough to capture their mismatched personalities on first try. These Rückenkatzen became the template for my weekly cartoon Catspeak at 3 Quarks Daily: Two cats with two very different outlooks on life—the clueless optimist who’s shocked at every piece of bad news and the world-weary cynic who expected it all along. The cats thank you, Caspar, and have made you a birthday card.

* I could always guess what my two cats were thinking when I saw them from behind. It was their body language. Unlike Friedrich, I do have trouble drawing. But I was lucky enough to capture their mismatched personalities on first try. These Rückenkatzen became the template for my weekly cartoon Catspeak at 3 Quarks Daily: Two cats with two very different outlooks on life—the clueless optimist who’s shocked at every piece of bad news and the world-weary cynic who expected it all along. The cats thank you, Caspar, and have made you a birthday card.

-Anyone in or near Manhattan between February 8 and May 11, 2025 should not miss the first major US exhibition of Friedrich’s works, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-I recommend Florian Illies’ Zauber der Stille as a fascinating and accessible collection of vignettes about Friedrich and the troubled destinies of many of his greatest works. A bestseller in Germany, the book will be out in English in November under the title: The Magic of Silence.

-For those who want to read more about the Rückenfigur, check out my Substack post on the subject.

the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.