by Malcolm Murray

Aella, a well-known rationalist blogger, famously claimed she no longer saves for retirement since she believes Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) will change everything long before retirement would become relevant. I’ve been thinking lately about how one should invest for AGI, and I think it begs a bigger question of how much one should, and actually can, act in accordance with one’s beliefs.

Tyler Cowen wrote a while back about how he doesn’t believe the AGI doomsters actually believe their own story since they’re not shorting the market. When he pushes them on it, it seems to be that their mental model is that the arguments for AGI doom will never get better than they already are. Which, as he points out, is quite unlikely. Yes, the market is not perfect, but for there to be no prior information that could convince anyone more than they currently are seems to suggest a very strong combination of arguments. We need “foom” – the argument, discussed by Yudkowsky and Hanson, that once AGI is reached, there will be so much hardware overhang and things will happen on timescales so beyond human comprehension that we go from AGI to ASI (Artificial Super Intelligence) in a matter of days or even hours. We also need extreme levels of deception on the part of the AGI who would hide its intent perfectly. And we would need a very strong insider/outside divide on knowledge, where the outside world has very little comprehension of what is happening inside AI companies.

Rohit Krishnan recently picked up on Cowen’s line of thinking and wrote a great piece expanding this argument. He argues that perhaps it is not a lack of conviction, but rather an inability to express this conviction in the financial markets. Other than rolling over out-of-the-money puts on the whole market until the day you are finally correct, perhaps there is no clean way to position oneself according to an AGI doom argument.

I think there is also an interesting problem of knowing how to act on varying degrees of belief. Outside of doomsday cults where people do sell all their belongings before the promised ascension and actually go all in, very few people have such certainty in their beliefs (or face such social pressure) that they go all in on a bet. Outside of the most extreme voices in the AI safety community, like Eliezer Yudkowsky whose forthcoming book literally has in the title that we will all die, most do not have an >90% probability of AI doom. What makes someone an AI doomer is rather that they considered AI doom at all and given it a non-zero probability. Read more »

CW: As the title suggests, there will be discussion of death and dying and some mention of suicide in this post.

CW: As the title suggests, there will be discussion of death and dying and some mention of suicide in this post.

Remember how Dave interacted with HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey? Equanimity and calm politeness, echoing HAL’s own measured tone. It’s tempting to wonder whether Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick were implying that prolonged interaction with an AI system influenced Dave’s communication style and even, perhaps, his overall demeanor. Even when Dave is pulling HAL’s circuits, after the entire crew has been murdered by HAL, he does so with relative aplomb.

Remember how Dave interacted with HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey? Equanimity and calm politeness, echoing HAL’s own measured tone. It’s tempting to wonder whether Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick were implying that prolonged interaction with an AI system influenced Dave’s communication style and even, perhaps, his overall demeanor. Even when Dave is pulling HAL’s circuits, after the entire crew has been murdered by HAL, he does so with relative aplomb.

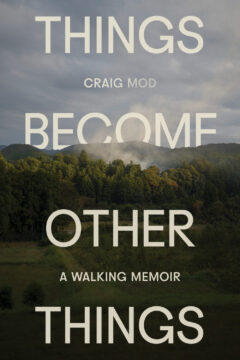

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

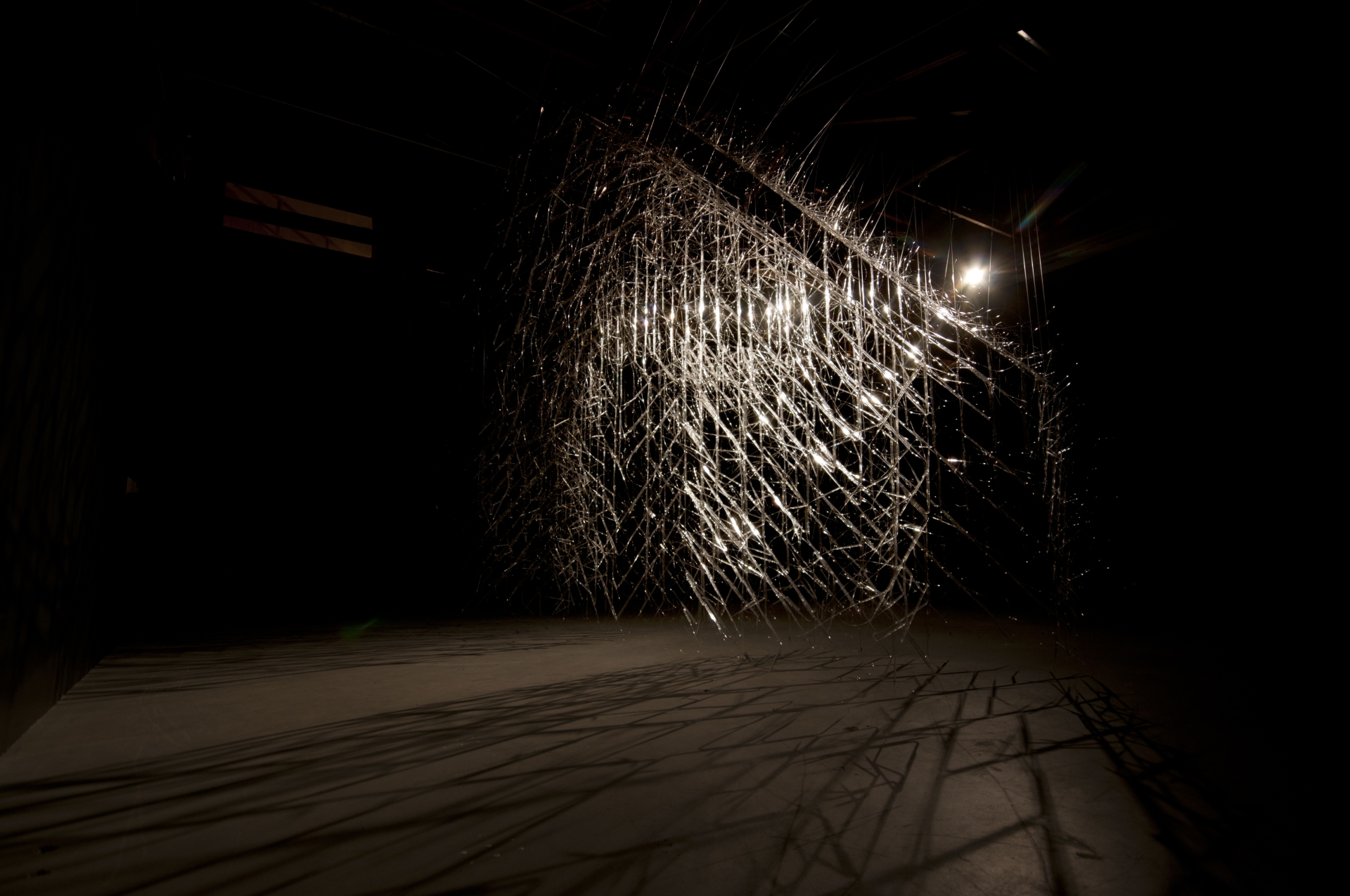

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing. Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions.

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions. In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.

In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.