by Michael Liss

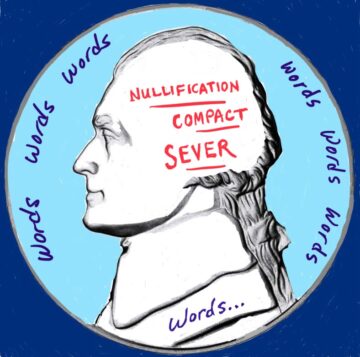

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

Words, so many words. Words that inspire “Ask Not,” and those that call upon our resolve “[A] date that will live in infamy.” Words that warn about the future “[W]e must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” and those that express optimism about it “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” Words that deny their own importance “[T]he world will little note nor long remember what we say here,” while elevating themselves and the dead they honor to immortality.

These words, these good words. They are the building blocks of our civic culture. In a democracy like ours, where we do not demand conformity, but rather abide by rules that are essentially an exchange of promises, words are paramount. What do they mean, how binding are they, do they express an unbreakable eternal truth, or do they grow sclerotic, even obsolete? If so, how do we change them? Is there an essence, a central truth that is and must be immutable?

To get any of those answers, we should begin with Jefferson, the central designer and primary wordsmith in the architecture of independence.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Wonderful, isn’t it? Thrilling. It is our intellectual origin story. It should fill us with pride—that, for these principles, we took on the most powerful nation on Earth and, after years of reversals, won. Soon we will celebrate the 249th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. We can trot out some nerdy historian to point out that maybe it’s not really the 4th of July—maybe it’s the 2nd or 3rd. We can indulge ourselves in cautionary reminders how perhaps we haven’t lived up to the promises that are in the Declaration. We can certainly bewail the state of contemporary politics. Or we can just enjoy it, maybe go to a small town if we don’t live in one, see the old cars and the pride of the older soldiers, the flags and bunting, the picnics, the fireworks, the tradition of a 4th of July speech by some local worthy.

Blather—of course it is. Like everything else, we commoditize it, commercialize it, invariably bury the lead: At its best, Independence Day should be a reaffirmation of the Declaration’s central promise. Read more »

January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well.

January 1, 2024. Happy New Year! Just eleven months and five shopping days before Election 2024. Whether you find it comforting that 2024 also happens to contain an extra day might be the best marker of how Political Seasonal Affective Disorder has impacted you. Personally, I haven’t been sleeping particularly well.

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people