by David Winner

When Taylor Swift was living in New York about a decade ago, she misused one of our classic expressions. Bodega means more than just corner store.

Tooling around Santo Domingo about the same time Taylor was living in New York, I stopped periodically at its ur-bodegas. Generally lacking what Americans call “amenities,” proprietors in the back dispensed individual cigarettes, candy, beer, rum. In the afternoons and evenings, the bodegas sometimes transformed into makeshift bars, cranked music, customers drinking booze, sometimes dancing.

Seven years ago, Angela, my wife, and I moved to the outer reaches of a Brooklyn neighborhood called Kensington that lies in between two crucial arteries – the car part stores, mosques and Bengali sweet shops of Coney Island Avenue and the grand fifties condos in not very picturesque decline on Ocean Parkway. Our neighborhood, reminiscent of Queens, is home to mélange of ethnic and cultural groups: recent middle-aged white additions like us; old school Irish/Italian/Jewish whites; Uzbeks, Tajiks and other Central Asians; Bangladeshis and Pakistanis; Mexicans; Afro and Indo Caribbeans, and lots of ultra-Orthodox Jews. These ethnic identities are not exactly reflected by our three closest bodegas: spaces that have become part of my landscape, geopolitical bell-weathers, and unfortunate victims of my big mouth.

Up our street past the Nigerian church, whose food pantry feeds thousands, you’ll find yourself at Mian’s corner store, which we refer to as “Donald’s bodega,” in honor of Donald, who spends most of his days hanging out there.

Donald, according to neighborhood lore, had fried his brain on drugs as a young man and somehow landed some lucrative disability. In his early sixties now with a paunch and sparkling white hair, we have never seen him in the company of friends or family. The bodega is his only social outlet. On the very rare days, Eid perhaps, that Donald’s is closed, poor Donald can be found in different less familiar bodegas on Cortelyou Road, looking uncomfortable outside of his native habitat.

Donald’s bodega is a ramshackle space with a random displays of snacks, household goods, an ATM, and a sandwich counter. On pleasant days, Donald sits or stands on the stoop. Bad ones find him inside the store occasionally talking to fellow customers or one of the three proprietors. Who each in his own way seems world-weary, tired, existentially disenfranchised. Two happen to be South Asian, but their perfectly idiomatic English and western clothes set them apart from the Bangla and Pakistani communities of very recent immigrants surrounding their store. The third proprietor, from Bulgaria, has an expansive grey beard and keeps his long grey hair tied up in a ponytail. Once, I came into the store to see him lecturing Donald about politics. Donald’s eyes were fogging over, not engaging or grasping the screed being explained to him. This was the one moment that I’ve observed politics entering Donald’s hallowed door. If the store were said to have a political point of view, it would be defeated, disengaged, adrift in long-lost battles in distant lands

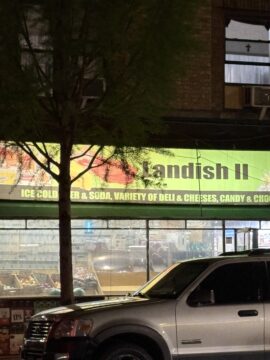

Across the street from Donald’s lies Landish Two. Lenny and Anna, the two owners from Ukraine, are of the generation of former Soviet Jews who were allowed to leave in the eighties sponsored by Jewish charities. Many went to Italy or Austria, then eventually Israel and the United States. Landish Two appears to be a far-off satellite of the stores in Little Odessa about four miles away. They sell pastries, breads, pickled vegetables and fresh, frozen, or canned Russian/Ukrainian delicacies. Russian TV is constantly on inside: talk shows and music videos. Svetlana, another Ukrainian woman, works the counter when Lenny and Anna are absent, and the store is cleaned and stocked by a tall silent Uzbek man who smokes constantly right outside the periphery of the store.

Caty corner from Landish Two lies our third and final neighborhood bodega, Sammy’s. When we first moved into the neighborhood, even Donald’s was pleasant in comparison, and I stayed well clear of its scattered old goods, dirty floor and dispirited atmosphere. When they closed down about a year after we’d moved nearby, I did not mourn its passing, hoping a happier more upbeat business might crop up in its stead.

But then, about three months later, it reopened as another bodega: entirely repainted with new floors and new glass in its windows. I went there several times, mostly to buy cheap headphones to run with, and the new owners (who I pegged rightly or wrongly as Yemenites) were excited about their new business. Unlike at either Donald’s or Landish, customers would be greeted enthusiastically upon entering the store, told to have nice days, beseeched to return soon, promised new innovations like a superior ice cream selection to come. We were even encouraged to come play with their adorable new deli-cat, the rodent protection for many bodegas.

The guys who ran it were young, wore western clothes seemed kind of callow, a bit thuggish but in a sweet way. But a new proprietor arrived with infinitely greater gravitas: tall, handsome, always wearing a traditional jebba. And when we entered the store, we heard the mesmerizing sounds of the Koran being chanted from some electronic device. I was never there at dawn but at Dhuhr (noon), Asr (afternoon), Maghrib (sunset), and Isha (night), he would be found on a prayer mat pointed from Coney Island Avenue towards Mecca. One evening, myself and a group of other likely non-believers (two Mexican guys and an African American woman) patiently waited for him to be done, one of those wonderful moments that keeps me from seriously considering leaving New York.

In the world outside of the bodegas in early 2022, terrible events started to occur. Putin invaded Ukraine. In those dire first weeks of the war when it looked as if Ukraine were about to crumble, Angela offered sympathy to the proprietors of Landish Two. Anna, Lenny, and particularly Svetlana were not sympathetic to their birth country. They appeared to admire Putin more than Zelinsky. What really rankled me was the transformation that occurred on their store television. Russian game shows appeared to have been replaced by Russian State TV.

One evening not long afterwards, I had drunk some wine and was hungry for a sweet. We all know the dangers of drunk-dialing and drunk-emailing, but I have to add drunk sweet-shopping to that benighted list.

I was waiting for Svetlana to take care of the customers in front of me when my attention turned to the television.

There were tanks. There were bombs. I could not understand the words, but sometimes context can be enough, or so I imagined. The somber voice on the television was surely explaining that Ukraine had invaded Russia, that what we were watching was the opposite of Russian aggression.

Rarely confrontational, I am terrible at confrontation. When activated, I choose awkward words and make ridiculous movements with my body like I’m a comedian in a silent movie.

Stamping my foot on the floor, my voice screechy and slurred, I point out to Svetlana the lies being told on television.

Her expression did not particularly change. She did not look angry, certainly not ashamed. She did not question my assumption about what was being said on her television though she knew full well that I did not speak Russian.

As I walked back home, I was suddenly sober and overwhelmingly sheepish. What I said may have been “right” but that did not make me “right” to say it. Make your own judgement, reader, I don’t expect charity.

Of course, I avoided the store for the next few weeks, not boycotting Russian state TV but avoiding the scene of my misbehavior. When I next entered (my profound need for paper towels and lemons overcoming by embarrassment), Anna not Svetlana was behind the counter and a Russian game show rather than a Russian news channel was on the television. Anna was perfectly pleasant as was I. Perhaps my outburst had indeed changed their television habits, but I’m sure they worried about alienating their customer base rather than reconsidering their interpretation of world events.

When I eventually ran into Svetlana, she too was pleasant, unshaken by my behavior through what she played on her TV was her choice, protected speech with which I should not have interfered.

*

Outside the bodegas, more darkness fell. The Hamas attacks, the Israeli savagery. At universities around the country, there were protests, occupations. But my Orthodox Jewish, Bengali/Uzbek Muslim neighborhood showed little interest. A Palestinian restaurant, opening near the Cortelyou train station, called the seafood section of its menu “from the river to the sea,” a dubious fusion of the political and the culinary, and one of the few neighborhood references to the conflict.

The US election was getting closer and Biden’s limp stance on Israeli genocide did not seem to bode well, given the importance of Michigan and its Arab American community. A sign appeared on Sammy’s door. Customers were urged not to vote for Biden in the name of Gaza.

Which brought up questions about the nature of voting. If we view it as an individual declaration of trust in the person for whom we’re voting, how could we vote for a man doing so little to stop murder and destruction? More of a lesser of two evils voter myself, though, I was focused on the dire consequences of a Trump presidency on Gaza and, obviously, the United States.

When I entered Sammy’s (perfectly sober, I swear) I took the sign as an expression of opinion on the part of the devout proprietor, the beginnings of a conversation, an invitation to dialogue. I felt the need to say something in my gut, sort of how we know we are about to cough, or sneeze, or vomit. But given my Landish Two assault, I was determined to be careful and considerate.

“I saw your Biden sign,” I think I began, “would it be appropriate for me to voice an opinion?” He nodded impassively.

Inarticulately, I explained that I hated Biden for not standing up to Israel, but if Trump won, many more Palestinians would likely die. Looking me in the eye, he listened, the pleasant expression remaining on his face. But he did not respond. I bought whatever I had intended to buy, said goodbye and left, feeling if not exactly good about myself, not as bad as after my Landish Two debacle.

When I next returned to Sammy’s, the sign was gone. Like Russian State TV at Landish Two, it had most likely not been removed because of my great wisdom but out of fear of deterring customers.

Then the devout man stopped working at the bodega, and a severe-looking older bearded man took his place who wore western clothes and had only a patina of an Arabic accent. Koran chanting had disappeared, replaced by silence.

Outside, Biden had dropped out and Kamala had ascended. Though she stayed far clear of the topic of Gaza, I still had some sense that she might do more to protect it than her predecessor. I wanted to know what the new proprietor thought about that.

Republican congressman, Henry Hyde, made grandiose gestures of disapproval after Bill Clinton fooled around with Monica Lewinsky in the Oval Office until Hyde’s own prior infidelity got exposed. Famously, he referred to it as a “youthful indiscretion” though he had already reached his forties. My foolish final bodega intervention seems like the foolishness of youth though my youth had ended decades before. Why, I just cannot imagine, did I somehow imagine that a long-removed political sign gave me permission to engage in political discourse with a stranger, a captive audience at a store? Two American dictums came into conflict here: don’t talk about politics or religion and the customer is always right.

In my defense, I can say that did not engage in polemics or self-righteousness. Rather, I had somehow found myself (nearly a senior citizen but clearly a junior reporter) on a sort of fact-finding mission.

“Can I ask you a question?” I asked the severe new proprietor at Sammy’s as I was handing over a twenty-dollar bill to buy whatever I was buying.

He shrugged his shoulders neutrally, neither yes nor no.

Then, apropos of nothing, as if we were friends in the midst of talking politics over coffee.

“Do you think, is it your opinion, that Kamala will be tougher on Israel than Biden? Could this be an improvement?”

Something strange started happening to his face. Blood flushed his cheeks as if he were blushing, but he was not blushing; he was enraged.

Standing completely still, not saying a word, he glared at me. And kept on glaring. Scorching me with his eyes.

“I’m sorry,” I told him. “I did not mean to offend. I was just asking your opinion.”

Which just made him angrier. Quickly, clumsily, I skulked away, feeling his eyes burrowing into me.

The man spoke perfect English. What did he hear in my words? Stand by Israel? Fuck Gaza? Or maybe he was a fervent Trump supporter, the very word “Kamala” just too much to bear.

May 2025

The Donald is president again, Ukraine apparently abandoned, Gaza destined to be cleared of Palestinians and turned into a resort, and back in our Brooklyn neighborhood, I seem to have grown out of my bigmouth ways.

Donald’s bodega remains the same though Donald himself grows pudgier and redder faced.

Landish Two has been struck by misfortunate. Lenny has a large benign tumor but has been too weak to have it removed. The distracted Anna has not baked her usual cakes and pastries. I’ve asked her how her husband is doing, a much more reasonable question for an acquaintance who runs a store you shop in, compassion rather than politics. She said that he was fine, but I didn’t think that he was.

I had not seen the angry bearded man at Sammy’s for many months. Much younger men, kids really, have been working their recently. But one evening, the bearded man was back, staring at me implacably. Both of us remembered whatever had happened before.

The song from which this essay’s title derives was written by Morrissey when he was still in his twenties before he revealed himself as a racist xenophobe in his fifties. And though I no longer listen to him for those reasons, the proprietor of Sammy’s may not have seen me as terribly different.

As I quickly pay, leave the store, and start strolling back home, I think of the valuable lesson that the proprietor taught me, one that I should have learned in my teens not in my fifties. Sometimes our politics should remain safely locked inside our brains while we keep our big mouths closed.

If there isn’t already, there should be some AI tool devised for our political outbursts. One that will allow us to win arguments against our political enemies.

My God you’re right, the newfangled Chat GPT version of Svetlana will tell me when I argue with her over my computer. Putin is a fascist. We must stand with Ukraine.

I don’t know what it would tell me about Kamala Harris and Gaza, and now it hardly seems to matter.