by David J. Lobina

‘Philosophy is a prolonged meditation on death’, so starts what may well be Mark C. Taylor’s 35th book, After the Human. A Philosophy of the Future, published by Columbia University Press. I must admit that I didn’t know Taylor’s work before reading this book, though this is perhaps unsurprising, as for most of his career Taylor seems to have focused on the study of topics and thinkers that are not particularly close to my own interests. This remains somewhat the case in After the Human: there is some discussion of Descartes and Kant – so, yea! – but there is far more of Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Derrida – a big nay.

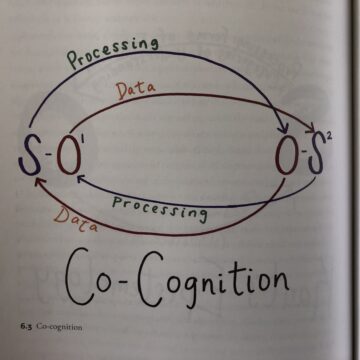

At the same time, Taylor devotes the bulk of his book to arguing that cognition is widespread in the world, from humans and other animal species to even plants and computer programmes, and all things cognitive are clearly up my street (by cognition Taylor means information processing tout court; more below). And yet most of the discussion keeps coming back to Hegel and co., even though most of the evidence, and some of the arguments, pertain to cognitive science proper and engaging with some of the contemporary literature in the philosophies of psychology and cognitive science would have been more fruitful considering the final result on display. I think this constitutes a missed opportunity.

I also think that in the end the book fails to deliver what it promises – a philosophy of the future – and instead God sneaks up on us quite unexpectedly at the very end, for no apparent reason (I should add that religion is one of Taylor’s areas of expertise, though it doesn’t feature all that much in the book). Before getting to the actual contents of the book, though, I would say that the volume could have done with a different style of argumentation.

The book is fairly eclectic, with various personal recollections intermixed with plenty of long quotes from a great number of thinkers and scholars. It is quite hard to keep up with, and keep track of, Taylor’s myriad references, points, and asides, and the presentation clearly could have benefited from a bit of signposting (oddly enough, though, the book is quite repetitive at times). In addition, and this may well be a personal shortcoming, I fear I missed out on a number of important points here and there, especially in relation to the many quotes from Hegel and company. I didn’t feel like a great many of these quotations helped the reader much or were added for the elaboration of a particular argument, but rather they were in there for exposition purposes and one needed to be acquainted with the ideas referred to already in order to understand them – and to understand how they fit in within the overall story Taylor wants to tell. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013.

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013. It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.