by Barbara Fischkin

Warren Wilson College

Swannanoa, North Carolina

Winter 1989

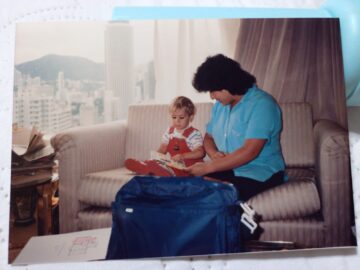

Now, it sounds exciting. And unusual. Back then I was terrified. I would be moving with my foreign correspondent husband from Mexico City to Hong Kong—a place I had never been—with a toddler and a Mexican nanny in tow.

Mari, the nanny, was calm. She was ready. And if she wasn’t, she knew how to fake it. Also, she had experience with children—and with difficult but necessary situations. She had left her own little ones with relatives back home in her small village to earn money in the capital. She was a mother who understood the long game. Sometimes short term pain was necessary for the goal of giving them a better life.

Still, I needed to make sure she really was ready for the big move, from one continent to another. She had never been out of Mexico.

Mari did not know it at the time but taking her from Mexico City to North Carolina—which one could do in those days without fear—was a test. If she could babysit while I attended a two-week fiction-writing residency at an isolated American college, close by an Appalachian mountain range, she could do Asia.

Why fiction? I already had a flourishing career in journalism. In Mexico City, I’d written a piece for the New Yorker and another one for the New York Times. But since I was a little girl, I wanted to be able to make up stories, too.

My first attempt at this, at around eight years old, horrified my mother. For good reason. I presented her with a short story about a child who swallowed her grandmother’s pills—as an “experiment”— and died. Although I did not understand this at the time, the story was my fictional turnaround of a real-life incident. At the age of two, I had found my real-life grandmother, my mother’s mother, dead in her bed from heart failure. It actually was a better-than-expected demise for my grandmother. She was born in an Eastern European shtetl. A brigade of Cossacks ransacked the shtetl. She survived, along with her husband and children, through a combination of luck and fortitude. Nevertheless, I don’t think my mother ever got over the fact that she was downstairs when I found grandma dead.

I have no idea why my first attempt at fiction switched a dead grandmother for a dead grandchild. These days, a mother presented with such “creativity,” would probably march her child off to the nearest kid-centered shrink. My mother just gulped. She also discouraged writing fiction. Read more »