by Barbara Fischkin

Warren Wilson College

Swannanoa, North Carolina

Winter 1989

Now, it sounds exciting. And unusual. Back then I was terrified. I would be moving with my foreign correspondent husband from Mexico City to Hong Kong—a place I had never been—with a toddler and a Mexican nanny in tow.

Mari, the nanny, was calm. She was ready. And if she wasn’t, she knew how to fake it. Also, she had experience with children—and with difficult but necessary situations. She had left her own little ones with relatives back home in her small village to earn money in the capital. She was a mother who understood the long game. Sometimes short term pain was necessary for the goal of giving them a better life.

Still, I needed to make sure she really was ready for the big move, from one continent to another. She had never been out of Mexico.

Mari did not know it at the time but taking her from Mexico City to North Carolina—which one could do in those days without fear—was a test. If she could babysit while I attended a two-week fiction-writing residency at an isolated American college, close by an Appalachian mountain range, she could do Asia.

Why fiction? I already had a flourishing career in journalism. In Mexico City, I’d written a piece for the New Yorker and another one for the New York Times. But since I was a little girl, I wanted to be able to make up stories, too.

My first attempt at this, at around eight years old, horrified my mother. For good reason. I presented her with a short story about a child who swallowed her grandmother’s pills—as an “experiment”— and died. Although I did not understand this at the time, the story was my fictional turnaround of a real-life incident. At the age of two, I had found my real-life grandmother, my mother’s mother, dead in her bed from heart failure. It actually was a better-than-expected demise for my grandmother. She was born in an Eastern European shtetl. A brigade of Cossacks ransacked the shtetl. She survived, along with her husband and children, through a combination of luck and fortitude. Nevertheless, I don’t think my mother ever got over the fact that she was downstairs when I found grandma dead.

I have no idea why my first attempt at fiction switched a dead grandmother for a dead grandchild. These days, a mother presented with such “creativity,” would probably march her child off to the nearest kid-centered shrink. My mother just gulped. She also discouraged writing fiction.

I moved out of the house—and eventually married. Then I then moved across the Atlantic Ocean to Ireland—far enough away from my mother to take another shot at fiction. I wrote a short story about an old Jewish man in Brooklyn. My husband said it was not nice to make fun of my real father in this format and suggested a title: “My Father The Accountant.” Yawn.

Years later, living in Mexico City, and apparently undaunted by earlier failures, I wrote a short story based on another nanny—Lilia, who was Mari’s predecessor and, as related in the previous chapter, a lot more trouble. I don’t remember much of this story. It is now stuck in a drawer somewhere. I do remember what I viewed as a particularly poignant scene in which a mother finds her baby’s nanny going through garbage retrieved from her own bedroom’s wastebasket. I must have been getting better at this, because that story led to my acceptance in a “low-residency” Master of Fine Arts fiction-writing program at Warren Wilson College. “Low-residency” back then meant being on campus for just two weeks a semester. The rest was what today we would call “remote.”

I was thrilled with the acceptance. But, with our move to Hong Kong, getting closer, this posed another dilemma. How, with a toddler to raise, would I be able to travel from Asia to North Carolina twice a year—and be away for two weeks each time? I had trouble leaving my little boy for a few days. So, I took advantage of another option offered by the college. I would merely attend the two-week residency and learn what I could. I decided to take my little boy—and Mari, his nanny —with me.

Not going for the degree was a decision I continue to regret. My mentor was the fiction writer Richard Russo, who went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for the novel Empire Falls.

“I would have enjoyed working with you,” he told me, when he heard I was not going to try to complete the degree. I still wonder if he could have helped turn my earlier drivel into good writing. Perhaps he would have found deeper—or funnier— meaning in the theft of my bedroom trash. Also, the MFA would have been a terminal degree, which I could have used the two or three times I tried without success to get full-time college teaching positions.

What I did not regret was taking Mari and my son to North Carolina. I think Mari understood little about my “ficción–escuela” nonsense—and could care less. She only cared about my son: Daniel David Mulvaney. We all called him Danny, although with Mari’s Spanish it sounded more like “Dani.” Her priority was exactly what I wanted: a good nanny, not a literary critic. I had a surfeit of those. Instead of staying in the Warren Wilson College dorms like my childless classmates, we rented a cottage nearby.

The biggest challenge was the mornings. Mari and I would get up with Danny, have breakfast and then, as I made my way to the door to leave for class, he would, in true toddler form, turn on the waterworks. “Mommy. Mommy. Mommy,” he wailed. This made me wonder if we all would have been better off if I had left him in Mexico City. Maybe Danny needed familiar surroundings more than he needed his mother. Children whose parents travel need a sense of stability. That’s why I wanted to take Mari with us to Hong Kong in the first place. I began to wonder why we needed this side trip to North Carolina.

Nevertheless, I got out the door every morning. It was no surprise to me that Mari was an expert at distraction. I had seen her do this in Mexico. Each morning, as I approached the door and Danny began to cry, she invariably found a toy or a story book or made a funny face. As soon as she had his attention, she shooed me out the door. I tried to erase the image of a crying child as I went from class to class. Each evening I’d return home to find Danny happily eating dinner after a day playing in the countryside. Each evening, the word “Mommy,” was delivered in a much happier tone.

I made up my mind after North Carolina. Mari would go home to see her children before we all left for Hong Kong, then return to Mexico City to help us pack. She would say goodbye to her friends and some of mine, including an American named Rosie, who was in Mexico City to study the Bel Canto style of opera. It was Rosie who found Mari for me. Mari had been looking for a new position, as often happened in Mexico City. Rosie described her as “stable, calm and a hard worker with a relatively sane life.”

All of which turned out to be true as we continued our journey, with a stopover in the United States and then on to Asia.

Hong Kong

June 1989

Looking back to this time, I think that Hong Kong, then a longstanding, flourishing British territory and Newsday—Long Island’s large, rich and only daily newspaper—had two things in common.

Denial.

And a recognition that uncomfortable changes were coming.

Newsday sent the four of us—me, my husband, Danny and Mari—off in style. First class air fare to Hong Kong with reservations at its tony Regent Hotel. The hotel fetched us at the airport in a Rolls Royce, as was customary. Even Mari’s reserve descended into near hysteria, as she got into the luxury vehicle, tightly gripping Danny in quivering arms. She said to my husband, “My home in Mexico has dirt floors. How did I end up in this car?”

Yet, even as Newsday did this, the bean counters back in a Melville, Long Island “neighborhood” of industrial parks,” knew the end of rich newspapers was nigh. Department stores, a main source of advertising, were closing, along with whispers of an Internet culture and the end of classified automobile ads.

Most of our Hong Kong neighbors acted as if Rolls Royces at the airport were normal occurrences and always would be. I wasn’t paying much attention but during our first days in Hong Kong, the so-called People’s Liberation Army of China was gearing up to massacre thousands of protestors in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Less than a decade later, in 1997, the Chinese army would be Hong Kong’s army as well. Hong Kong would revert to the despotic rule of China. Along with cherishing the Rolls Royce mentality, the expats worried they might not be living their luxurious corporate-supported lives forever. The locals, the ones who could, made plans to move to Vancouver.

As Tiananmen Square exploded, pictures of massacred students were displayed at the boarding site of Hong Kong’s Star Ferry. A daily reminder that the future would be different. It was especially grim to me, my husband was in Tiananmen Square during the massacre, a tale that needs a chapter of its own,

The banality of daily life took my mind off geo-politics. We enjoyed the glories of colonial Hong Kong— the boutiques, the restaurants, the outings on teak boats, courtesy of Newsday’s largesse in posting us there.

We set up housekeeping in a duplex apartment, part of a new development that looked out over the South China Sea. It had three bedrooms—one became the Newsday Asia bureau office. The cost? A mere $6,800 a month American dollars. The paper also paid the same for a comparatively tawdry apartment in Beijing. Our Hong Kong abode had a state-of-the-art playground and a bigger-than-Olympic size swimming pool with a large children’s area. It is significant that nannies—called amahs in Hong Kong, a Cantonese word with some Portuguese derivation from neighboring Macau—were not permitted in the pool. They had to sit by the sparkling chlorinated water, rather than in it, watching their charges in water wings and tubes.

The swimming pool rule also applied to Mari. It did not matter that she was Mexican, not Filipina as most of the local “help” was in those days. Dark skin or even the suggestion of dark skin was the dividing line in Hong Kong no matter where it originated. Mari took this in her stride. Back in Mexico City she plunged whenever she pleased into our backyard swimming pool with Danny. In Hong Kong she was stoic: Rules, no matter how unfair, were rules. Mari obeyed them. (Not everyone did. One expat father regularly took a gaggle of amahs swimming in the pool after dark).

Mari was lonely in Hong Kong. The other nannies spoke Tagalog or different Filipino languages. She spoke Spanish and only a little English. I assuaged my guilt remembering the deal we had made. She would only spend a few months in Hong Kong to get us acclimated, making more money than she had in Mexico. The raise would help improve life for her children. She would get to see Asia. I had told her that whenever she felt she had to go home, she could.

There was one heartbreaking moment, when Mari called home to her small village in Mexico from a phone booth. She reached one of the few phones in the village, in a shop. When someone in the store answered, all she needed to do to gather a crowd of her hometown relatives and friends was to say. “It’s me Mari. I am calling from China. China!” She pronounced it in her proper Mexican Spanish as Chee-na.

Eventually Mari found a kindred spirit. It wasn’t one of the amahs, but rather an expat wife looking for a playmate for her little girl, who was the same age as Danny. Oddly, she lived in our building, stories above us. We had never run into each other on the elevator. One day on the shuttle bus from our development to the neighboring market town of Stanley, Spanish chattering pervaded the bus. Mari and I were talking while Danny listened, when all of a sudden this other expat mother— a lovely woman named Louise—chimed in, with her Tex-Mex accent. After that Mari often took Danny upstairs to play with Louise’s little girl, Selena.

I do not remember too many more stories about Mari. She was loving and steady, unlike her predecessor Lilia. Mari was focused on her job, not trying to be dramatic. What I do remember is that one day while she was bathing Dan, she looked uncharacteristically cranky and annoyed. I guessed what was wrong.

“Mari,” I asked. “Do you want to go home?” She nodded. “Si senora.” Mari could have volunteered this information. Instead, she had waited for me to ask.

On the appointed day, I took Mari, by taxi, to the international airport where we had been picked up by that Regent Hotel Rolls Royce. Danny was with us. Mari’s last words to me were “cuida de Dani.” Take care of Danny. I assured her I would. I also hired the best Filipina amah I could find to replace her. To this day those farewell words of Mari’s ring hard in my ears. Before we left Hong Kong, Danny became so ill with a virus that he needed to be hospitalized for a few days for dehydration. My husband and I took turns in his room so that he would always have a parent by his side. We knew he was getting better when my husband brought our younger son, still an infant, into the hospital to see him, after obtaining our pediatrician’s approval. “Put my brother in my bed,” Danny said and my husband did.

Danny recovered and returned to pre-kindergarten classes at a Montessori school in Stanley. He was a bit distant when it came to playing with others but the teachers assured me this could be normal after a hospitalization, even a short one. Then…slowly…Danny started losing his language. He has been able to speak English communicatively and also spoke appropriate words in Spanish, Cantonese and Tagalog. He developed other troubling symptoms. Around the same time, Newsday decided to close its costly Hong Kong venture and send us back home to Long Island. Once there, we brought the now-wordless Danny to specialist after specialist. Eventually Yale diagnosed Danny with “Childhood Disintegrative Disorder-Cause Unknown.”

It is one of the most severe and often mysterious diagnoses on what is now widely known as the Autism Spectrum. Informally, what Danny had contracted is called “late-onset autism,” because it hits children after prolonged development.

Those were such grueling years, with two little boys who both needed a lot of attention even—or because— one of them was severely disabled. I often thought about Mari but until this year, I didn’t remember if she was in touch with us after leaving Hong Kong, if she knew about how Danny had changed.

Back in Touch With Mari

On the afternoon of January 7, 2025, I received this email sent to me through my Authors Guild-hosted website.

Hello Ms. Fischkin,

I hope you are well. I am Jennifer Reyes Garcia. I am contacting you on behalf of my grandmother Maria de Los Angeles Garcia. We believe she was Danny’s nanny in Mexico years ago. She is here visiting me in California and we took advantage of her time here, to see if we could find you since you made such a positive impact in her life and would love to reconnect.

Hope to hear back,

Jennifer and Maria de Los Angeles Garcia

Indeed, this grandmother named Maria De Los Angeles Garcia seemed to be our Mari. I hoped this was true. I logged on to her Facebook Messenger and asked if she had traveled outside of Mexico with us. “Si, Hong Kong,” she replied. Yes, this was our Mari. We exchanged photos and information. It also seems, although I am not sure how, that she did know about Danny. Perhaps she saw photos about him—he has his own Facebook page. He still has autism and is mostly non-speaking. He lives near us in a wonderful group home with three housemates and a full-time staff, including a live-in house manager. He is a hard-working volunteer at two organic farms, surfs large ocean waves with courage and aplomb and plays ice hockey, skating with a team of folks with autism or similar disabilities. Mari wrote me that Danny was living a good life .

Mari’s granddaughter, who recently earned a BA in Economics from a college in the California Bay area, has kept in touch, as well. As for Mari, she wrote this to me on Facebook Messenger, in Spanish. Here is my translation, which Mari’s granddaughter checked for me:

“For me it was an honor to have met you, it was a dream come true to travel while taking care of your baby. Enjoying the beaches of Hong Kong with Danny as my companion of the day was an honor. On my return to Mexico I joined Eusebio with whom I had three sons: Omar, Adiel and Jose Isabel. Altogether I have a total of five children, now grown. Four sons and a daughter. I was married and five years ago I was widowed but here I am standing and putting a lot of effort into my life. It was a joy to have contact with you again and know that you are well. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

She added more information: My husband worked in the state judicial police and when he left that job he went to the United States. He stayed for a while and came back and we set up a stall, selling tamales, atole and flavored waters. This is how we got our children ahead. One of my sons is a teacher!”

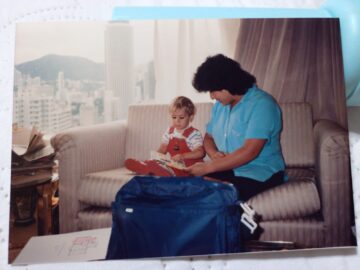

Mari had kept many photos of herself and Danny in Hong Kong. She sent me copies. One of them is displayed above. And now, we are back in touch, often sending each other short but warm messages. It feels good to be connected with the Mexican woman who traveled with us to Hong Kong. I used to think of her as simple. She was much more She was strong. She was brave. She loved Danny. And she helped our family a lot.