by Michael Liss

Ay! I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which one of us will be happiest! —George Washington to John Adams, March 4, 1797

No one in American history has ever known better how and when to make an exit than George Washington. Just two days before Washington left for the figs and vines of Mount Vernon, the Revolutionary Directory of France issued a decree authorizing French warships to seize neutral American vessels on the open seas. There was a bit of tit-for-tat in this—in 1795, America had negotiated the Jay Treaty to resolve certain post-Independence issues between it and the British, including navigation without interference. But France was at war with England, and, while France wasn’t necessarily looking to shoot it out with the Americans, it did want to disrupt trade. Adams moved quickly to prepare the country, but the French were on a war footing, the Americans were not, and, by the end of 1797, roughly 300 American merchant ships with their supplies and crews had been taken. This was the so-called “Quasi-War.” Adams was deft with diplomacy—he sent a team to Paris to negotiate an end to the open hostilities, but they (supposedly) were met with demands for large bribes as a predicate for discussions (the “XYZ Affair“). The country seethed.

We Americans love to say that “politics stop at the water’s edge,” but it is kind of a comforting lie. Politics almost never stop, water’s edge or not, and that was certainly true in the Spring of 1798. Federalists prepared for war, pointing out the obvious—France didn’t exactly look like a friend. Democratic-Republicans claimed Federalists were manipulating the situation as a pretext to centralize power in their own hands, and to drive a wedge between America and its sister nation, Revolutionary France.

Of course, they were both at least a little right. America was trying to figure it all out. Beyond the bigger conflicts with Europe, there was something interesting at this moment going on in American politics. Politicians and voters were adding political identities, along with their regional and state-level ones. They were further sorting themselves into temperaments and teams inside the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties—so it was not just two combatants, but several, across a spectrum. It was all so new. In just a generation, we had gone from being 13 colonies, to being loosely tied States under the Articles of Confederation, to having a federal government with real authority. A lot of Americans, including those in elected office, didn’t really know how conflicts would be resolved between the individual and his State, his State and the federal government, or among the federal government’s three branches. The one thing that was not new was human nature—the tendency to remember the convenient, to fill the space of ignorance with self-interest, to believe in one’s own “rightness,” and to thirst for power.

Timing matters. For the first eight years of our new form of government, we had the unifying presence of George Washington. Now the Presidency is occupied by John Adams, a great patriot, of course, but a bit challenged in the charisma department and even more so in the “admiration” one. Democratic-Republicans mock him; his Cabinet (mostly Alexander Hamilton supporters), almost to a person, detests him and often works against him; and his fellow Federalists are distant in their affections. Outside of his brilliant and loyal wife Abigail and his talented son John Quincy, the number of John Adams fans is, well, uninspiring. That small and select cadre does not include his Vice President, a gentleman by the name of Jefferson, who used to be his friend, until little things like politics and ambition got into the way.

We are at a critical pivot-point in American politics, in which there are terrific, pent-up centrifugal forces affecting public life, both internally and externally. It’s hard to find stability, particularly when one Party, the Federalists, hold pretty much all the federal political power, and the other party, the Democratic-Republicans, hold pretty much all the political talent.

For the Federalists, post-Washington, that problem starts at the very top. Adams, however devoted he is to his country, remains an 18th Century man, uninterested in the emerging world of partisan politics. He’s just not a joiner; he’s not a natural, and he can’t fake it. Backslapping and spittoons are just not his thing. His view of the Presidency is more akin to Washington’s—a figure of unity who floats above the fray because, as Chief Executive, his first job is to create consensus. That’s a lovely conceit, but Washington was Washington, and Adams is Adams, and that concept, as appealing as it might have been, had no more chance than it would today. “Unity” is not something Americans do or have ever done particularly well.

Of course, what Adams lacks is what Jefferson, James Madison (and Alexander Hamilton) all have in abundance—a very strong sense of the necessity of Party to govern—and an affinity for power best achieved by using Party. We might note that there’s a certain amount of intellectual “flexibility” to Madison, who had been eloquent on the mortal dangers of faction in Federalist 10, but, putting aside a bit of cynicism, Madison’s conversion actually seems to validate itself. The future of American politics will be a Party-driven one. Madison, primary architect of a Constitution that attempts to buffer factionalism, has come to realize that unilateral disarmament just leaves the other guy in charge. From the moment he and Jefferson formed the Democratic-Republican Party in 1792, they felt themselves ready for command, and used their newly created vehicle to achieve it.

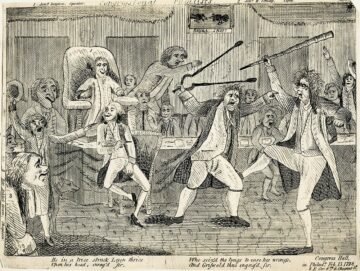

Adams’ victory over Jefferson in 1796 infuriated the Democratic-Republicans, as did Adams’ retention of the old, Hamilton-dominated Cabinet. Four (more) years was a long time to wait, and so the heckling of Adams, Federalist officeholders generally, and Federalists policy preferences became all-encompassing. Politically aligned media (obviously, in those days, print media) dove in with a zest for fiction-laden hyperbole.

In truth, it was more than heckling, and some of it could be laid right at the door of the Sage of Monticello. Jefferson and Madison, driven by some amalgamation of idealism and opportunism, began to focus on Adams as a repository of evil. Federalists clearly wanted to turn back the Revolution of 1776, roll back freedoms, etc. and Adams was the criminal mastermind at the center of it. Nothing he did could be taken at face value, all was part of some terrible plot to subjugate the country, to bend it to his will. This Jefferson and Madison could not let happen, so they determined that Adams must be opposed at every juncture—even where there might be some unity of interests.

One can question the fairness and even appropriateness of this folie à deux—surely both Madison and Jefferson were far too intelligent to swallow it all. Adams wasn’t the type to play well with others, but his patriotism was beyond dispute. He took far more risks, sacrificed more, took up far more unpopular causes on behalf of his countrymen than either Jefferson or Madison.

It’s easier to give Madison a pass. He’s an opposition politician trying to put together a winning coalition at a time of serious, legitimate challenges. As for Jefferson, one can feel a bit less generous. Jefferson was Vice President. Yes, the rules prior to the adoption of the 12th Amendment created this situation—a President and a Vice President could be of opposite political parties—but, for a Vice President to work actively to undermine the President and his entire agenda is more the stuff of television drama than behavior that most people would think appropriate. As Washington’s Secretary of State, Jefferson had resigned over policy differences. As Adams’ Vice President, he chooses to stay, to spread a little dirt, to gather inside information, to whisper to his allies, even to pass information on to those select foreigners who could be potential adversaries. In short, this is one of his lesser moments.

It is, in fact, a period of time in which many politicians are having lesser moments, but the weight of popular opinion is on the side of the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists are simply more stultifying—the country had embarked on this experiment in freedom, and the Federalists now seem like the starchy old Headmaster with an affinity for lectures on well-ordered deportment. Most of their time seems focused on consolidating power in centers that would be permanently controlled by them. The public, quite reasonably, questions why the country would fight a revolution to get away from a monarch, only to replace him with a monarchical form of government.

With the problems with the French acting as a catalyst, both sides begin down the slippery slope of defining their policies and philosophies as not only better than the other’s, but essential to the survival of the nation. Since the Federalists have the power, and are surely aware of the upcoming Midterms, they look to exercise it.

Enter, the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. Certainly, in the aggregate, these are among the most reviled laws passed by that or any other Congress (impressive when you think about the competition). They are also the subject of fierce debate in Congress, with Federalists sometimes joining Democratic-Republicans in objecting.

The Acts were actually four separate pieces of legislation, each with its own target, and each with a certain resonance even today. I’d add that Adams, to his eternal discredit (and embarrassment) signed them all, although he tried to ameliorate their impact.

The Naturalization Act of 1798, which raised the residency requirement for citizenship from five to 14 years, effectively ended the potential political influence of immigrant groups. As one might expect, it wasn’t all immigrants the Federalists wished to muzzle, but they did want to stem the flow of the French and Irish, given both groups’ alarming tendency to vote Republican. That wouldn’t do. The Naturalization Act of 1798 was repealed by the new Democratic-Republican government in 1802. A footnote to history.

The Alien Friends Act of 1798, passed by Federalists over significant Democratic-Republican opposition, authorized the President, for almost any reason, to use extraordinary powers to deport aliens from any nation, without a hearing or an opportunity to appeal the President’s decision. Its utter lack of due process would almost certainly render it unconstitutional today (we think). Adams never actually deported anyone under the Alien Friends Act, although it had to have influenced certain would-be immigrants. This Act expired at the end of 1800 (presumably because the Federalists realized they might lose the 1800 Election) and was not renewed. It’s an interesting curio.

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 empowered the President to detain non-citizens during times of war, invasion, or predatory incursion. This Act, once amended to strike out the section making it applicable only to males, is still around, and has been used three times, in each case during a war (most notoriously, the Japanese internment). After lying dormant for nearly 75 years, it’s been embraced with an unbridled passion by President Trump and is now before the Supreme Court. A topic for a different day, but the fact that it remains on the books arguably shows its importance if exercised with restraint and moral certitude.

The Sedition Act of 1798 criminalized critical statements about the federal government, the President, or Congress. One can make the argument that Americans had no concept of a loyal opposition, but that argument would be a weak one. The text itself is startling—just to quote in part:

That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them…

Extraordinary, isn’t it? Note also who was not included on the “don’t be mean to him” list—the Vice President, who just happened to be Thomas Jefferson. You could be as mean as you wanted to him.

The four bills passed Congress by narrow margins in July 1798, and almost instantaneously set off mass protests across the country. Not merely were the bills objectively partisan, designed to enhance the Federalist’s hold on office and generally tighten the central government’s hold on power, but they struck at what Americans felt were basic rights. Jefferson took up his pen for North Carolina (initially, eventually his words were used in a Kentucky Resolution). James Madison wrote for Virginia. The talents of both were on full display, eloquently dismembering the intellectual and moral framework of the Acts. Jefferson’s was less disciplined, and some of his harshest language never made it into the final version, which was probably wise.

Predictably, the prosecutions that derived from the Sedition Act were entirely partisan. Bear in mind that the publishers that ended up on the docket were not exactly babes in the woods. They were just doing what some media figures have done for as long as publishing has existed—whether in newspapers, books, handbills, magazines, and anything else you could think of—trafficking in false, scandalous and malicious writing, along with perfectly factual, but critical news and opinion.

The first prosecution might have been the most predictable: The widely despised (and widely read) Benjamin Franklin Bache, editor of the Philadelphia Aurora, a Democratic-Republican newspaper, and a rag beyond reproof. In 1798, he was charged with libel for remarks made about President Adams which included comments about his hairline and teeth, along with criticism for alleged nepotism and bad policy towards France.

Other targets included James T. Callender, a Scottish emigree, who may or may not have been paid off by Jefferson for some nasty stuff about George Washington and, more intimately, about Alexander Hamilton (and his affair with Maria Reynolds). In the book The Prospect Before Us (previewed by Jefferson), he slammed the Adams Administration and added some choice words about Adams himself. Callender was convicted and sentenced in 1800. Later, ostensibly because of his pique over not being sufficiently rewarded by Jefferson, he wrote about the then-President’s relationship with Sally Hemmings.

In all, roughly two dozen men walked the plank of the Sedition Act. Ten were convicted, four of those Democratic-Republican-aligned newspaper editors. The prosecutions included one man, a common laborer named Luther Baldwin, who, after having a few, shouted that he did not mind if a cannon salute for a presidential procession shot Adams in the rear. A local newspaper reported the incident, and Baldwin was fined $100.

The truth was that every single one of those prosecutions sank the Federalists a little deeper into the trench of oblivion. Not all defendants were heroic, but all paid a price for what had to be an unconstitutional law. They became martyrs—the more eloquent of them able to articulate the value of the rights being denied them, and, by extension, possibly all Americans.

It’s amazing how much self-harm a frightened group of pols can achieve by convincing themselves that gross overreach will always carry the day. It wasn’t just the words. The Federalists also did enormous damage to themselves with their nativist approach in the Naturalization Act of 1798, both by saying out loud what previously had been whispered, and by motivating those already in the United States to register, if they qualified under existing rules and had given notice of their intent. So much for the Irish. At the same time, their call for a larger standing army and military appropriations caused them to grossly mishandle their relationship with the Germans, a key constituency in places like Pennsylvania. By early 1799, German communities were organizing, sometimes assembling militias to protest the taxes. The Fries Rebellion led to arrests, trials, and convictions for 30 participants. Three men, including Fries, were convicted of treason and sentenced to hang. At this point, John Adams stepped in, pardoned Fries and the others, and later issued a general amnesty, but there would be no political absolution.

In the end, the American people spoke. Jefferson defeated Adams in 1800, while Adams was actually outperforming other Federalists. The Party was in its death throes. They still had a redoubt in New England, and there were still Federalist Judges, but the Party’s support melted away. By 1804, not only had Jefferson overwhelmed Charles Pinckney (Jefferson got 72% of the popular vote), but his party held the House 114-28 and the Senate 27-7.

Vox Populi. The Federalists had been swept away. There is a fragment from Jefferson’s “Resolutions Relative to the Alien and Sedition Acts,” November 10, 1798, that seems apt.

[F]ree government is founded in jealousy, and not in confidence; it is jealousy and not confidence which prescribes limited constitutions, to bind down those whom we are obliged to trust with power: that our Constitution has accordingly fixed the limits to which, and no further, our confidence may go….

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.