by Steve Szilagyi

A curious part of getting old is seeing people you knew in life turned into bronze statues. You preserve a vivid impression of some laughing, breathing person; they disappear for a while; then they pop up again as a stolid, staring statue. The transition from flesh to effigy can be disquieting. Heroic idealization is out. Too many of today’s statues strain to show their subjects as ordinary people—mannequins on the brink of the uncanny valley. And just to make sure you don’t mistake them for anything grand or lofty, they are placed at or near ground level, so you can stare right into their cold, dead eyes. Where once a pedestal raised a figure into the air like a great, godly hand, many of today’s statues simply stand on the street like day laborers looking for work. The idea, I suppose, is to make them more like the rest of us—but really, what’s so great about the rest of us?

The question of who deserves a public statue creates argument—and even more so, the question of whose should be torn down. To set a figure above the crowd immediately raises people’s hackles. How dare you stand up there, staring down as if you were better than me? Yet some people are better than others, and Central Park’s Literary Walk reminds us of this without fuss. The statues of William Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, and Sojourner Truth stand on proper pedestals, so that you must raise your face to see them—and so become a child, and experience a child’s sense of awe.

Inviting selfies. For myself, I’m happy to acknowledge that Shakespeare, Scott, and Truth were better people than I. It’s a little harder to summon the same feeling when confronting statues of some contemporaries. There’s a pretty good statue of Willie Nelson in Austin. Set at a decently respectful height, the statue’s warm expression and relaxed pose invite selfies. Across town, Stevie Ray Vaughan cuts a stranger figure—stiff and off balance, as if uncertain whether he belongs in bronze at all. And in Seattle, there’s a grotesque representation of Jimi Hendrix, squatting just above the sidewalk, stroking his guitar. What will future generations make of this? Will they identify him as a cultural force, or simply see an open-mouthed wild man? Read more »

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

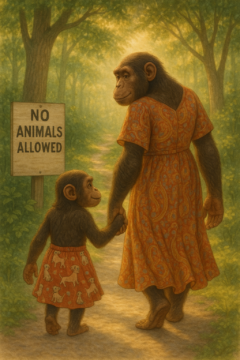

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

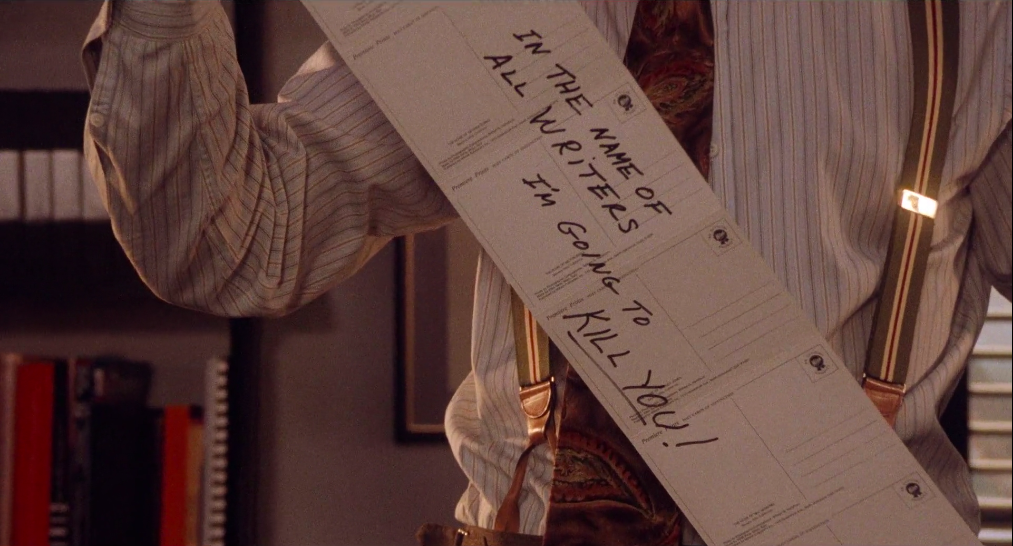

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea: