by Kevin Lively

Introduction

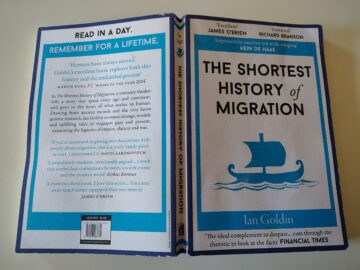

It is a well-worn observation that a sense of fatalism seems to be settling across the peoples of the world. There is a wide-spread feeling that global developments are echoing trends from the 1930s. Economic centers in the USA are gearing up their domestic industrial capacity, while the defense department speaks of Great Power Competition. China does the same, while trenches and mines scar the fields of Ukraine. With the NATO alliance under question, Europe begins to look after its own industrial base while refugees from drought-stricken, strife-torn lands drown in the Mediterranean. Those who manage a safe arrival, both in Italy as in Texas, often struggle to integrate into an aging society despite a desperate need for young workers. Substantial and growing fractions of the US and European populations are of the mind that this influx of hands — ready and eager to work — should not be turned to repairing crumbling bridges or staffing overworked retirement homes. Rather they should be banished and sent away in disgrace, regardless of the final destination.

An unspoken thought seems to be flowing among the currents beneath many people’s minds. More and more often now, it seems to break to the surface at unexpected times. Here’s a drinking game: every time you hear some variation of the phrase “in today’s geopolitical climate”, take a shot. Depending on where you work and what topics your lunch conversations drift towards, it may be unwise to play this game on a weekday. These events increasingly beg for certain pressing questions to be asked.

For example: how do we, as a species, deal with these dislocations of people, and the disruptions to their means of supporting themselves? How do we, as a species, plan for the future dislocations to come, as crop cycles grow increasingly unpredictable and failure-prone, while the ocean’s fish are replaced with plastic as ever more forms of pollution with unknown consequences accumulates? How do we, as a species, allocate this planet’s apparently dwindling resources between ourselves in order support a simple life of dignity and peace, unburdened by the deprivation of extreme poverty and the chaos it brings?

Discussions around such questions are, by necessity, discussions of death, religion, power and land — among the topics best avoided both at Thanksgiving and a bar. Thus there is a tendency to tread carefully around them while in polite company. Yet in today’s geopolitical climate it increasingly behooves us all to address such questions in a sober and critical manner. Ideally we should all have some mutually understood context for the stage on which these events are playing out, whether we’re in the audience, on the gantry or elsewhere, busy prepping the smoking lounge in your bunker. Read more »

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

CW: As the title suggests, there will be discussion of death and dying and some mention of suicide in this post.

CW: As the title suggests, there will be discussion of death and dying and some mention of suicide in this post.

Remember how Dave interacted with HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey? Equanimity and calm politeness, echoing HAL’s own measured tone. It’s tempting to wonder whether Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick were implying that prolonged interaction with an AI system influenced Dave’s communication style and even, perhaps, his overall demeanor. Even when Dave is pulling HAL’s circuits, after the entire crew has been murdered by HAL, he does so with relative aplomb.

Remember how Dave interacted with HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey? Equanimity and calm politeness, echoing HAL’s own measured tone. It’s tempting to wonder whether Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick were implying that prolonged interaction with an AI system influenced Dave’s communication style and even, perhaps, his overall demeanor. Even when Dave is pulling HAL’s circuits, after the entire crew has been murdered by HAL, he does so with relative aplomb.

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

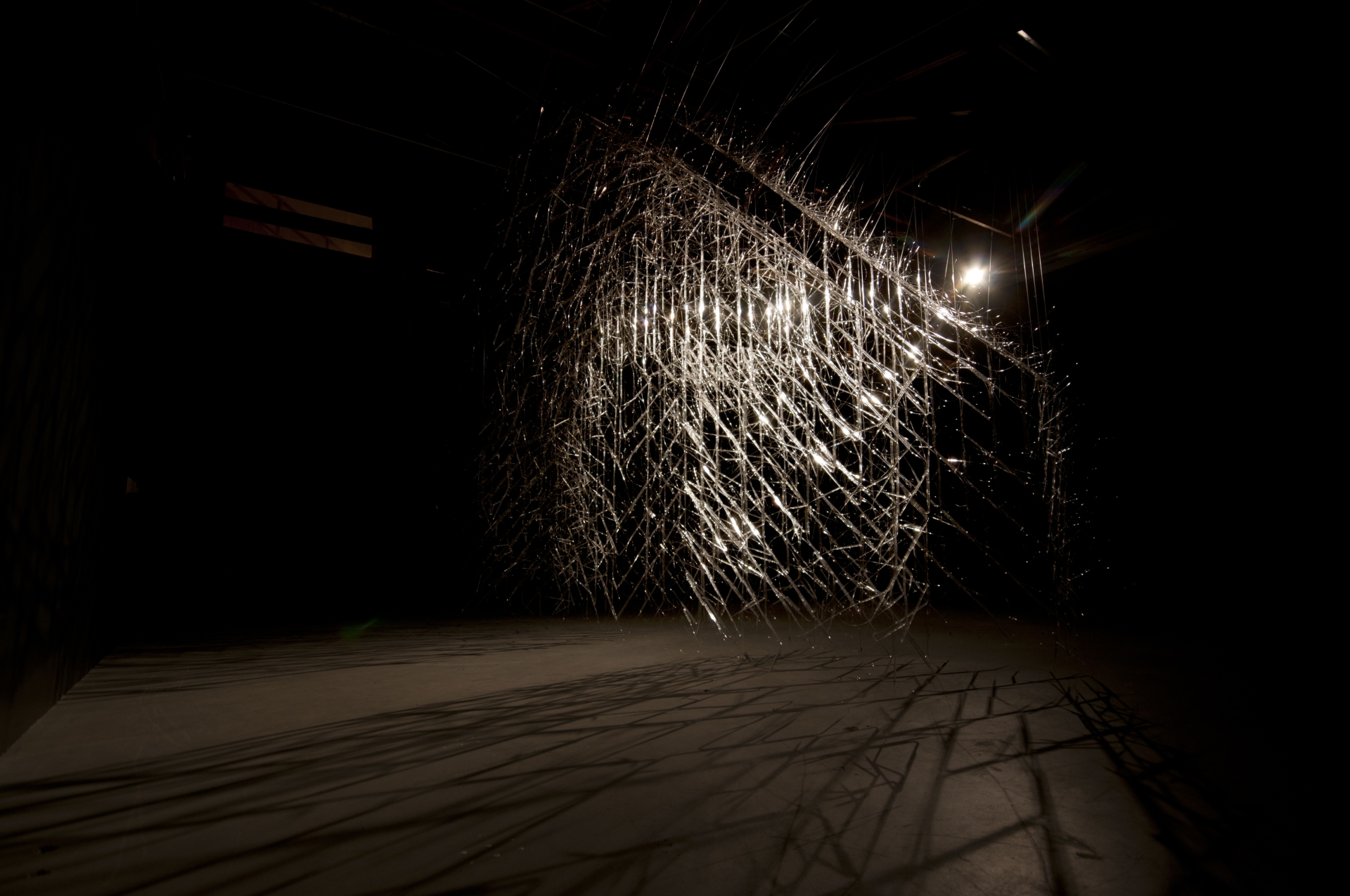

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing. Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.