by Jochen Szangolies

Mind, it seems to us, is a closed-door affair: without taking any strong stance on how, it is surely related to what the brain does; and the brain does its thing in the dark cavern of the skull. Thus, the content of your mind and mine seem divided by an unbridgeable gap. How could then disparate minds ever come together to form a greater unity?

For a first hint of how the mind might flee its bony confines, consider the extended mind thesis of philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers. They observe that many of our cognitive functions are not restricted to the tools internal to our brains: rather, we use various technologies that enhance our abilities beyond what would be possible using our grey matter alone. Think, for instance, of a simple notebook, the paper kind: writing things down can enormously enhance memory of those of us that tend towards a certain forgetfulness. Using pen and paper, calculations can be performed that are impossible to keep in the mind all at once. A diary allows you to recall what you had for breakfast today ten years ago, which is far beyond most people’s memories. To say nothing of more sophisticated gadgets, like calculators, computers, or smartphones.

Clark and Chalmers substantiate their thesis by discussing the case of Otto, who has Alzheimer’s disease, and for whom a notebook acts like a kind of cognitive prosthesis: it is not too difficult to imagine that, as long as Otto has access to his notebook, he could perform much in the same way as he did before cognitive deterioration started to set in. Concretely, they posit that he navigates a museum together with Inga, whose cognitive faculties are unimpaired. Both find their way equally well; the only difference is that Inga’s memory is processed internally, while Otto relies on an external aid.

That this should be possible in principle follows from the idea of substrate independence. It seems exceedingly chauvinistic to claim that mind could only exist within the sort of neural circuitry that constitutes human gray matter. What if we eventually encountered aliens that use some different machinery for their cogitation? Should we consider them barred from club conscious just on principle? This does not seem a reasonable stance. Rather, whatever fulfills the same role that neural circuitry does in our case should do just as well. But then, why not a notebook?

If mind is able to vault the bounds of its confinement, then language is the pole that allows it to do so. Language uses symbolic vehicles to give physical form to abstract meaning, be it in terms of sound, marks on paper, or other signals like waving flags. Language is the tool I am using right now to transmit ideas—ideally—from my brain into yours, where I might hope they find fertile ground to take root and grow. Encapsulated into words, sentences, and paragraphs, concepts arising in my mind leave their sheltered origins and venture into the wider world, like those very first proto-cells spilling out of the rock-pores of hydrothermal vents. The extended mind doesn’t necessarily stop at the boundaries of another’s skull: successful communication may be a literal meeting of minds, in this sense.

But minds can reach beyond themselves in other ways, too. Consider how many authors report resistance of their creations against their dictates: a sudden refusal to obey, an insistence to act of their own accord. This ‘illusion of independent agency’, as Jim Davies, director of the Science of Imagination Laboratory at Carleton University terms it, might even involve authors entering into a dialogue with their creations. If the author wishes a character act a certain way, but the character refuses, then according to whose wishes is this refusal framed? Is this just the author in conflict with themself, perhaps using the character to voice some unconscious ‘true’ intent against his own surface intentions? Or is there indeed a degree of true agency here?

The notion seems fanciful, but may not necessarily be so. The philosopher John Searle, in contemplating whether machines could ever be said to properly ‘think’, formulated his famous Chinese room-argument. Searle imagines himself inside a room, closed off to the outside save for a slot through which slips of paper can be passed back and forth. He receives notes with Chinese symbols printed on them—which, knowing no Chinese, are perfectly opaque to him. However, he has a vast book of symbol-manipulation rules—the putative program a computer might use to ‘understand’ Chinese—that tells him, for any configuration of characters, how to formulate a ‘response’—naturally, just as opaque as the query that prompted it. This continuing failure to divine the meaning of the slips of paper being passed back and forth, Searle claims, shows that no machine merely instantiating a program could ever be said to properly understand Chinese—or any language.

The most popular response to this is that Searle, in the above setup, is only a part of the whole system that generates responses in Chinese. We might not expect him to understand any more than we might expect the CPU of a computer on its own to do so, but this doesn’t entail that there is no understanding in the whole system, comprising Searle, the slips of paper, and the rulebook.

Searle reacts to this objection, which he anticipates, first with simple incredulity: it is just ridiculous, he proposes, to think that “while [the] person doesn’t understand Chinese, somehow the conjunction of that person and bits of paper might”. Proponents of the extended mind-thesis, however, might well disagree. But Searle offers a more considered rebuttal. Imagine that he, gifted with a prodigious memory and intellect, memorizes the whole rulebook, and thus, internalizes the entire ‘system’. Yet still, when engaging in Chinese ‘conversations’, he will have no inkling of their content.

But suppose now you asked Searle, in English, about the name of the first Chinese emperor, which Searle, we may stipulate for the sake of example, doesn’t know. Then ask him again, in Chinese: it is entirely possible that he would reply correctly, naming Qin Shi Huang Di. Chinese-speaking Searle might have items of knowledge English-speaking Searle does not; and likewise, he might have beliefs, preferences, desires, hopes, and so on. In short, he might be an entirely different character from English-speaking Searle.

If we follow that logic, then we might surmise that Searle, with the mighty cognitive act of memorizing the entire rulebook, has in fact succeeded in instantiating another mind within his own—just like a Windows-PC might instantiate a virtual Linux-machine. Call such a mind, hence, a virtual mind. If such virtual minds are possible, might it not be the case that we—pretty routinely—engage in the act of creating ‘mini’ minds that maybe fall short of full persons, but aren’t quite co-extensive with our own selves, as well? (Extending the computational metaphor, we might term these container minds, after virtual containers that isolate certain applications from the host operating system, but fall short of full virtual machines.) Davies’ illusion might not be so illusory after all!

Indeed, in the end, most of us have probably encountered this effect. Who has not, after spending some time immersed in a fictional universe, felt the spectre of characters that have become deeply familiar looking over their shoulders? Such mental endosymbiosis—the taking of residence of one mind within another—is not limited to fictional persons, of course. Douglas Hofstadter, author of the celebrated Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, wracked with grief upon the death of his wife Carol, writes in his 2007 book I am a Strange Loop:

The name “Carol” denotes, for me, far more than just a body, which is now gone, but rather a very vast pattern, a style, a set of things including memories, hopes, dreams, beliefs, loves, reactions to music, sense of humor, selfdoubt, generosity, compassion, and so on. Those things are to some extent sharable, objective, and multiply instantiatable, a bit like software on a diskette. […] I tend to think that although any individual’s consciousness is primarily resident in one particular brain, it is also somewhat present in other brains as well […].

Swarming Minds

It is not just human minds that, occasionally, seem to leak out into the world. Consider starlings flocking or ants building their intricate colonies: there is agency there, but it is not the agency of any single individual. Rather, this agency exists on the level of the collective: no ‘first starling’ decides which way to turn, no master builder ant holds the blueprints and directs the workers. When a group comes together in the right way, what emerges is best described not as the actions of a collection of individuals, but as those of a compound entity, a swarm, a hive—or a nation, a corporation. Legally, after all, corporations have been considered persons for a long time—and the argument has been made that our modern world is not really geared to the needs of the individual human, but to those of massive, transnational corporate entities.

Support for the notion that mind can reach beyond its traditional dwelling place somewhere within the brain comes from one of the most well-developed mathematical theories of consciousness: the integrated information theory (IIT) developed, chiefly, by University of Wisconsin neuroscientist Giulio Tononi. IIT proposes that there is a certain quantity, the integrated information Φ, of systems that measures the degree to which they are conscious. As the name implies, it quantifies the integration between different subsystems of a compound system—roughly, Φ = 0 means that all parts of a system evolve independently of one another, while a high Φ denotes a high degree of interconnectivity. But this interconnectivity is not limited by substrate, but simply by organization: there is no in-principle obstacle to having a high Φ in a system consisting of a brain and a notebook, or even of two or more brains. On the other hand, just because something happens in the same brain doesn’t necessarily imply a uniformly high Φ—certain regions might be highly connected internally, but share fewer connection to the wider network, thus leading to ‘encapsulated’ container minds.

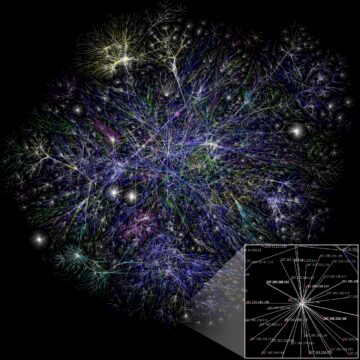

Even without buying into the tenets of IIT wholesale, that mind is more a product of organization rather than substrate, that it is more important how parts of a system interconnect rather than what they consist of, seems a plausible premise. But if there is one central phenomenon of our age, it surely must be the ever-increasing interconnectedness of individual humans: where we were, in past times, largely limited to a kind of ‘local’ information interchange—talking to people physically present—, we can nowadays instantly connect and share thoughts with minds half a world away. The internet is the latest stage in mind’s evolution towards higher complexity: if not true multicellularity, then maybe something comparable, in terms of relative complexity, to bacterial films showing significant collective behavior. Or perhaps more appropriately, the internet may be to mind what soil is to life: a formless substrate, from which all manner of crops may spring—nutritious grains and noxious weeds alike.

Under this conception, the internet may be likened to (an embryonic version of) the noosphere, a planetary ‘sphere of reason’ conjectured by the Jesuit priest and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. While Chardin’s theories can hardly be said to pass scientific muster, his ‘law of complexity’ could be considered a precursor to the entropic theory of England, and the elaboration sketched here. Taking the analogy seriously, we should expect this noosphere to further grow in complexity and interconnectedness, perhaps at some point in the future incorporating the mentations of artificial non-human minds—which are the ultimate end point of the detachment of mind from substance, freely taking residence in whatever computational architecture suits their needs. But the details of this planetary awakening, should it ever take place, we will leave for future speculation: for our purposes, it suffices to note that the assumptions made in extrapolating our individuality into the far future are less obvious than is usually realized.

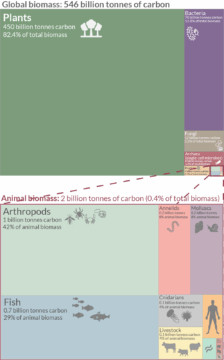

In short, mind, like life, is not necessarily best described in terms of single, discrete instances: boundaries blur and distinctions erode, minds may merge or incorporate miniminds, agency can become distributed across large groups. Even today, minds are not strictly separated from one another, but are part of an ecology that grows ever more highly interconnected. Mind continues the journey towards greater levels of integration that was begun when molecules first figured out how to form structures stable against entropic decay. Just as life did not remain a collection of individual cells, we should thus perhaps reconsider the assumption that mind continues as a collection of individual minds. There are, perhaps, fewer individuals today than a lone eukaryotic cell might have expected some billion years ago; yetat the same time, there may be more life, but most of it is part of a multicellular being. (One estimate has the global total biomass at 550 Gt carbon, of which 450 Gt are plants, dominated by macroscopic land plants.)

But seriously, who wants to be the Borg?

If the argument as presented so far is cogent, then the puzzle of our early existence does not necessarily spell doom: most sentient beings in the universe will find themselves in a position comparable to ours, not because almost all civilizations wipe themselves out before reaching for the stars and founding a galactic metropolis, but because the future is not one of individual entities. In projecting our current state of being towards the future, assuming it to be filled with quadrillions of distinct minds, we are making the same error a single cell in the distant past would have made in considering the present to be an age of vast quantities of individual cells. Mind, like life, in evolving towards ever higher complexity, will eventually hit upon strategies of merging, clustering, and compounding—a trend which we can observe even now.

But even so, two questions still loom large. What, actually, does it mean for mind to evolve beyond isolated individuals? And, is this actually a fate better than—or markedly different from—our eventual extinction? Science fiction, after all, is replete with cautionary tales where falling under the thrall of a ‘hive mind’ is portrayed as a fate worse than death—as in Star Trek’s Borg, an alien race whose individuals are cyborg-zombie creatures slaved to the will of the hive, stripped of their individuality and used—and expended—as replaceable drones.

Such cautionary tales, however, typically turn on a certain kind of paradox: that of an ego shackled to the will of the collective. There is, thus, both an individual and a non-individual consciousness, and the former is subject to the latter, all the while striving to be free. There is, in the phrasing of Thomas Nagel, still something it is like to be an individual Borg, and this experience is that of being dominated by an alien will, being merely a passenger in one’s own head. The fear of enslavement within a collective agency is thus something of a failure of the imagination: we continue to posit an individual point of view while attempting to imagine its lack.

This in itself is not surprising: after all, the sum total of our experiences is framed from within an individual perspective. We cannot step outside of our own individuality to examine it, because the very act of examination already seems to presuppose such a perspective.

However, there are challenges to this view. In contemplative practices, such as those related to Buddhist or Taoist traditions, we find the concept of nonduality: the idea that we are not separate from one another and the rest of the world. Through various forms of meditation, it is claimed that we can approach this nonduality, reaching a state of ‘ego-dissolution’ or even ‘ego-death’. Moreover, this is usually framed as a desirable outcome: clinging to ego is clinging to unfulfillable desires, which lead to inescapable dissatisfaction.

While I won’t comment on the soteriological aspects of such teachings, there is a highly relevant ethical corollary: within a nondual conception, all harm of others becomes akin to self-harm. If you and me are not, ultimately, perfectly distinct individuals, then me hurting you, whether physically or in any other way, is not just ethically damnable, but simply nonsensical—like cutting off a perfectly functioning thumb. Such actions are transformed from being morally wicked to being just plain dumb—and thus, a remedy against them may be found not in the acceptance of some moral code, but in simple education.

In this vein, the argument has been made that in order to meet the interlocking threats of planetary crises, of climate change, the looming spectre of nuclear war, of rising nationalism—of doom, in other words—we may have to embrace what the German philosopher Thomas Metzinger calls Bewusstseinskultur: literally a ‘culture of consciousness’, fostering adaptive, positive states of consciousness and contemplation against the egoistic and jingoistic culture of greed, conflict, and exploitation of natural resources for the benefit of a privileged few.

The evolution towards non-individual ‘multicellular’ mind then may not only be a safeguard against the statistical likelihood of doom, but also, more concretely, the way to avert (or at least weather) the very real crises currently threatening human flourishing. And thus we come, finally, to this essay series’ ultimate point—which, coming so late in the game, may appear a somewhat odd volte face, or at the very least a cheap bit of rhetorical sleight of hand. But I ask your indulgence for a couple more paragraphs.

Certain beliefs become reasonable only once they are held. Consider the belief of a student that they will do well in an important presentation: failing to believe so, their insecurity may lead to a nervous and unconvincing performance; but adopting this belief may just be the reason for its truthfulness. They give a confident, well-presented talk, winning over their audience and convincing them of their arguments. Once they believe they’ll do well, then, they’re justified in their belief. Prior to their belief, however, they lack sufficient reason to rationally form it. Believing sometimes makes it so.

This point was raised by William James in his 1896 lecture The Will to Believe. James’ context was religious faith, but his argumentation has a wider appeal—in particular, in instances where those holding a certain belief are instrumental to the conditions for its truth. And this is the situation we, humanity as a whole, find ourselves in, at this historical juncture.

For doom is still very much in the cards: even if the evolution towards more complex structures of mind, as outlined above, is feasible, none of it needs to happen. If we wipe ourselves off the map with a massive nuclear exchange tomorrow, the puzzle of our early existence finds just as definite an answer: there will be no later.

The author of an essay such as this one should, at its end, hope to have made their case cogently enough to have convinced the reader of their point—or at least, to have managed to communicate it well enough to allow an informed decision. It is tempting to content myself with this hope, and leave the rest to you. But with an issue such as this one, where belief may be part of the antecedent conditions for its own justification in the Jamesian sense, disbelief is equally as reasonable: we might not come together if we don’t believe we will, and thus, believing we won’t will be borne out eventually. Between these two opposing poles, then, a rational adjudication is impossible. Argument and reason can do no better but leave you with this Kierkegaardian leap to one or the other.

So my final point is a naked appeal to you, dear reader, to find in yourself the will to believe that a different—better—future is possible. That we are not doomed. That we can band together, and overcome the threats we face, by overcoming the narrow self-minded opportunism that created them. That finally the brooks, streams, and rivulets of individual minds will not, one by one, peter out to leave the universe dry and deserted, but disembogue into a sea of being, leaving the silt and detritus of disconnected strife and struggle behind.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.