by Ed Simon

Alternating with my close reading column, every even numbered month will feature some of the novels that I’ve most recently read, including upcoming titles.

A novel, like a symphony, must be conveyed through a particular artistry of time. Unlike a painting, or even a short lyric poem which gestures towards narrative, a novel must dwell in it. Even a novel where “nothing happens” must by the nature of the form make its art happen through the progression of a past into the future, but it in the complexities of that transition – the roundabouts, the flashbacks, the shifting, the slip-streaming, the ruminations, and the foreshadowing – which makes extended prose so adept at conveying the ambiguous feeling of time itself. Within a novel, time can be treated as anything but simple, so that the past can find itself perennial; the future can be a matter of precognition; the present an eternity (or, conversely, nothing at all). “Where there is no passage of time there is also no moment of time, in the full and most essential meaning of the word,” writes the Russian Formalist critic Mikhail Bakhtin in his The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. “If taken outside its relationship to past and future, the present loses its integrity, breaks down into isolated phenomena and objects, making of them a mere abstract conglomeration.” The abstraction of the present is what some mediums exult at – whether lyric or painting – but a novel can’t help but exist amidst the texture of time, its warp and warble, its nicks and snares.

The Spoiled Heart by British novelist Sunjeev Sahota masterfully interrogates time, in particular time’s daughter of memory and its cruel son trauma. Published in April, Sohata’s novel is set in industrial Chesterfield, a small hamlet in Derbyshire. Focalized around the local union leader Nayan Olak, though narrated by his occasional childhood friend Sajjan Dhanoa who is equal parts roman a clef and Nick Carraway, The Spoiled Heart is set in a realistic England distant from many Americans’ country house fantasies. Working-class and multicultural, tough and often despairing, this is the England not necessarily of Blenheim and Wentworth Woodhouse, or even of red phone-booths, double-decker buses, and fish and chips, but rather of kebab houses and labor politics, strikes and stark class divisions. Nayan, the son of Indian Sikh immigrants, suffered hideous trauma twenty years before, when as a young man barely into his 20s a seemingly accidental fire in his parent’s High Street shop killed his mother and young son. The tragedy destroys Nayan’s marriage so that in between caring for his bitter and demented father, he ultimately dedicates his life to Unify, a union representing laborers across a variety of industries. Having decided to run for the presidency of Unify, Nayan is challenged by his colleague and former friend Megha Sharma. Where Nayan is a class-essentialist leftist of the Corbynite variety, Sharma – also the daughter of Indian immigrants, albeit from a well-heeled class – is an adherent to an identity-focused liberalism. Much of the drama from The Spoiled Heart derives from the ideological and personal friction between these two.

But were Sahota’s novel only a means of allegorizing post-Brexit and post-covid fissures in the British left it wouldn’t be nearly as fascinating, and moving, as it is. Read more »

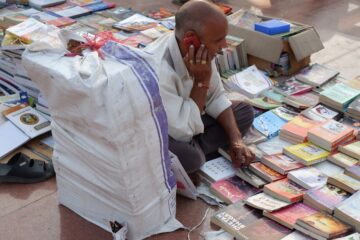

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

Dhingra’s book is built on many months of Sundays spent walking the market, talking to traders and readers, and mapping the bazaar’s assemblages and syncopations. I was lucky enough to tag along on one of these expeditions in July 2023. Arriving empty-handed, we traced a circuitous route between tables piled high with dog-eared paperbacks under billowing canopies. I departed clutching lucky finds: a 1950s Urdu story collection and a strange out-of-print children’s novel called

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

In 2007, at the Munich Security Conference, Vladimir Putin announced that the current world order had changed. The unipolar world order, with one centre of power, force and decision-making, was unacceptable to the leader in the Kremlin. Yet, more than that, Putin’s speech prepared the replacement of the unipolar world order, a replacement, he would later come back to, over and over again: multipolarity.

One argument for the existence of a creator /designer of the universe that is popular in public and academic circles is the fine-tuning argument. It is argued that if one or more of nature’s physical constants as mathematically accounted for in subatomic physics had varied just by an infinitesimal amount, life would not exist in the universe. Some claim, for example, with an infinitesimal difference in certain physical constants the Big Bang would have collapsed upon itself before life could form or elements like carbon essential for life would never have formed. The specific settings that make life possible seem to be set to almost incomprehensible infinitesimal precision. It would be incredibly lucky to have these settings be the result of pure chance. The best explanation for life is not physics alone but the existence of a creator/designer who intentionally fine-tuned physical laws and fundamental constants of physics to make life physically possible in the universe. In other words, the best explanation for the existence of life in general and ourselves in particular, is not chance but a theistic version of a designer of the universe.

One argument for the existence of a creator /designer of the universe that is popular in public and academic circles is the fine-tuning argument. It is argued that if one or more of nature’s physical constants as mathematically accounted for in subatomic physics had varied just by an infinitesimal amount, life would not exist in the universe. Some claim, for example, with an infinitesimal difference in certain physical constants the Big Bang would have collapsed upon itself before life could form or elements like carbon essential for life would never have formed. The specific settings that make life possible seem to be set to almost incomprehensible infinitesimal precision. It would be incredibly lucky to have these settings be the result of pure chance. The best explanation for life is not physics alone but the existence of a creator/designer who intentionally fine-tuned physical laws and fundamental constants of physics to make life physically possible in the universe. In other words, the best explanation for the existence of life in general and ourselves in particular, is not chance but a theistic version of a designer of the universe. Sughra Raza. Scattered Color. Italy, 2012.

Sughra Raza. Scattered Color. Italy, 2012.