by Michael Liss

Ay! I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which one of us will be happiest! —George Washington to John Adams, March 4, 1797

No one in American history has ever known better how and when to make an exit than George Washington. Just two days before Washington left for the figs and vines of Mount Vernon, the Revolutionary Directory of France issued a decree authorizing French warships to seize neutral American vessels on the open seas. There was a bit of tit-for-tat in this—in 1795, America had negotiated the Jay Treaty to resolve certain post-Independence issues between it and the British, including navigation without interference. But France was at war with England, and, while France wasn’t necessarily looking to shoot it out with the Americans, it did want to disrupt trade. Adams moved quickly to prepare the country, but the French were on a war footing, the Americans were not, and, by the end of 1797, roughly 300 American merchant ships with their supplies and crews had been taken. This was the so-called “Quasi-War.” Adams was deft with diplomacy—he sent a team to Paris to negotiate an end to the open hostilities, but they (supposedly) were met with demands for large bribes as a predicate for discussions (the “XYZ Affair“). The country seethed.

We Americans love to say that “politics stop at the water’s edge,” but it is kind of a comforting lie. Politics almost never stop, water’s edge or not, and that was certainly true in the Spring of 1798. Federalists prepared for war, pointing out the obvious—France didn’t exactly look like a friend. Democratic-Republicans claimed Federalists were manipulating the situation as a pretext to centralize power in their own hands, and to drive a wedge between America and its sister nation, Revolutionary France.

Of course, they were both at least a little right. America was trying to figure it all out. Beyond the bigger conflicts with Europe, there was something interesting at this moment going on in American politics. Politicians and voters were adding political identities, along with their regional and state-level ones. They were further sorting themselves into temperaments and teams inside the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties—so it was not just two combatants, but several, across a spectrum. It was all so new. In just a generation, we had gone from being 13 colonies, to being loosely tied States under the Articles of Confederation, to having a federal government with real authority. A lot of Americans, including those in elected office, didn’t really know how conflicts would be resolved between the individual and his State, his State and the federal government, or among the federal government’s three branches. The one thing that was not new was human nature—the tendency to remember the convenient, to fill the space of ignorance with self-interest, to believe in one’s own “rightness,” and to thirst for power. Read more »

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions.

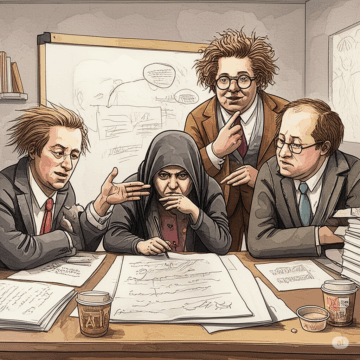

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions. In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.

In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.

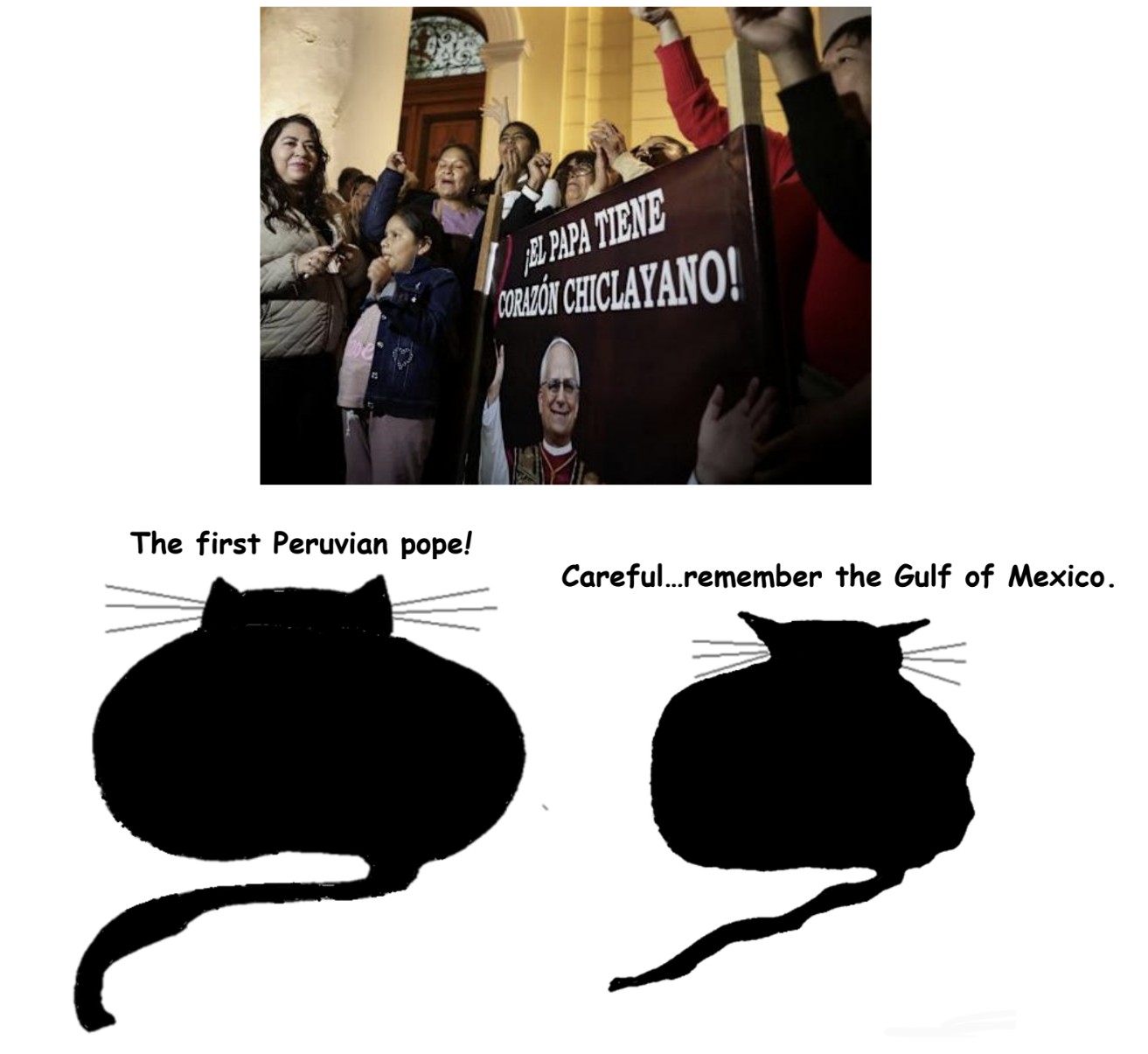

s on a common topic. Yet at noon on May 8th, all 16 high school seniors in my AP Lit class were transfixed by one event: on the other side of the Atlantic, white smoke had come out of a chimney in the Sistine Chapel. “There’s a new pope” was the talk of the day, and phone screens that usually displayed Instagram feeds now showed live video of the Piazza San Pietro in Rome.

s on a common topic. Yet at noon on May 8th, all 16 high school seniors in my AP Lit class were transfixed by one event: on the other side of the Atlantic, white smoke had come out of a chimney in the Sistine Chapel. “There’s a new pope” was the talk of the day, and phone screens that usually displayed Instagram feeds now showed live video of the Piazza San Pietro in Rome.

Danish author Solvej Balle’s novel On the Calculation of Volume, the first book translated from a series of five, could be thought of as time loop realism, if such a thing is imaginable. Tara Selter is trapped, alone, in a looping 18th of November. Each morning simply brings yesterday again. Tara turns to her pen, tracking the loops in a journal. Hinting at how the messiness of life can take form in texts, the passages Tara scribbles in her notebooks remain despite the restarts. She can’t explain why this is, but it allows her to build a diary despite time standing still. The capability of writing to curb the boredom and capture lost moments brings some comfort.

Danish author Solvej Balle’s novel On the Calculation of Volume, the first book translated from a series of five, could be thought of as time loop realism, if such a thing is imaginable. Tara Selter is trapped, alone, in a looping 18th of November. Each morning simply brings yesterday again. Tara turns to her pen, tracking the loops in a journal. Hinting at how the messiness of life can take form in texts, the passages Tara scribbles in her notebooks remain despite the restarts. She can’t explain why this is, but it allows her to build a diary despite time standing still. The capability of writing to curb the boredom and capture lost moments brings some comfort.

Many have talked about Trump’s war on the rule of law. No president in American history, not even Nixon, has engaged in such overt warfare on the rule of law. He attacks judges, issues executive orders that are facially unlawful, coyly defies court orders, humiliates and subjugates big law firms to his will, and weaponizes law enforcement to target those who seek to uphold the law.

Many have talked about Trump’s war on the rule of law. No president in American history, not even Nixon, has engaged in such overt warfare on the rule of law. He attacks judges, issues executive orders that are facially unlawful, coyly defies court orders, humiliates and subjugates big law firms to his will, and weaponizes law enforcement to target those who seek to uphold the law. When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.

When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.

Elif Saydam. Free Market. 2020.

Elif Saydam. Free Market. 2020.