by Alizah Holstein

Here are some books that have long been available for consultation on Level 2 of Pusey Library, which is not exactly a library in itself but an underground extension of Widener Library at Harvard. The Erotic Tongue: A Sexual Lexicon; The Erotic in Literature: A Historical Survey of Pornography as Delightful as it is Indiscreet; Eros: The Meaning of My Life; and Truth and Eros: Foucault, Lacan, and the Question of Ethics.

You might choose a Paris café to read your Foucault, but Pusey Level 2 in fact seemed to me back then, in the 1990s, like the ideal place for Ivy League eros. It was fitting for New England, I thought, perfectly representative really, that scholarship on erotica be consigned to a distant and wholly underground location. In our eleventh-grade French class, our teacher liked to say, “Symbolisme, mes amis,” while we watched Hiroshima mon amour with our eyes peeled for symbols.

At that time I worked at Widener, and it too was rife with symbols. To get to Pusey book storage from the circulation desk, you take a tiny, rickety elevator down to Level D, the lowest level, always empty, which you traverse in dim light, passing incidentally by the Dante section, also consigned (fittingly?) to the library’s lowest rung, and where I also liked to fritter away time. Passing Dante, you push open a set of heavy doors. The wind from the corridor beyond pushes against you, a strong headwind. Which should be noted is a feature of the bottommost pit of Dante’s Inferno—Lucifer, the fallen angel, bats his wings and creates a windstorm, which freezes the water of the lake in which he stands, icing himself stationary, for being motionless is the very definition of Hell, in Dante’s terms, motionlessness being the absence of motion—and motion, of course, is movement, which entails both sensuality and intellect, which when harnessed together, lead to a higher understanding of love and virtue. In Dante’s terms at least.

I always found this deserted wind tunnel between Widener and Pusey a heady space, a liminal place where my physical body felt freed and my mind full of hope and idea. But this might be because when I worked at Widener in the 1990s, I was eighteen, and as a circulation desk employee, I was corralled behind a desk for hours a day. Or maybe it was because real freedom of any kind was still a thing so new that even in its most mundane form—a break from work—it tasted sweet.

Also sweet was the feeling of having a theory. In this case, that Harvard librarians placed the university’s collected monographs on eroticism in Pusey’s moveable stacks because the underground location symbolized their suppressed sexuality, and that that location furthermore was accessible through an obviously Freudian tunnel. Read more »

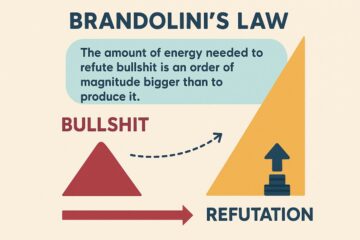

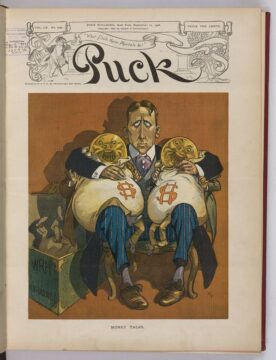

As atrocious, appalling, and abhorrent as Trump’s countless spirit-sapping outrages are, I’d like to move a little beyond adumbrating them and instead suggest a few ideas that make them even more pernicious than they first seem. Underlying the outrages are his cruelty, narcissism and ignorance, made worse by the fact that he listens to no one other than his worst enablers. On rare occasions, these are the commentators on Fox News who are generally indistinguishable from the sycophants in his cabinet, A Parliament of Whores,” to use the title of P.J. O’Rourke’s hilarious book. (No offense intended toward sex workers.) Stalin is reputed to have said that a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. Paraphrasing it, I note that a single mistake, insult, or consciously false statement by a politician is, of course, a serious offense, but 25,000 of them is a statistic. Continuing with a variant of another comment often attributed to Stalin, I can imagine Trump asking, “How many divisions do CNN and the NY Times have.”

As atrocious, appalling, and abhorrent as Trump’s countless spirit-sapping outrages are, I’d like to move a little beyond adumbrating them and instead suggest a few ideas that make them even more pernicious than they first seem. Underlying the outrages are his cruelty, narcissism and ignorance, made worse by the fact that he listens to no one other than his worst enablers. On rare occasions, these are the commentators on Fox News who are generally indistinguishable from the sycophants in his cabinet, A Parliament of Whores,” to use the title of P.J. O’Rourke’s hilarious book. (No offense intended toward sex workers.) Stalin is reputed to have said that a single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. Paraphrasing it, I note that a single mistake, insult, or consciously false statement by a politician is, of course, a serious offense, but 25,000 of them is a statistic. Continuing with a variant of another comment often attributed to Stalin, I can imagine Trump asking, “How many divisions do CNN and the NY Times have.”

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013.

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013. It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.