by Jochen Szangolies

Mind, it seems to us, is a closed-door affair: without taking any strong stance on how, it is surely related to what the brain does; and the brain does its thing in the dark cavern of the skull. Thus, the content of your mind and mine seem divided by an unbridgeable gap. How could then disparate minds ever come together to form a greater unity?

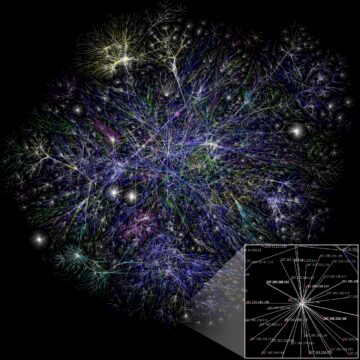

For a first hint of how the mind might flee its bony confines, consider the extended mind thesis of philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers. They observe that many of our cognitive functions are not restricted to the tools internal to our brains: rather, we use various technologies that enhance our abilities beyond what would be possible using our grey matter alone. Think, for instance, of a simple notebook, the paper kind: writing things down can enormously enhance memory of those of us that tend towards a certain forgetfulness. Using pen and paper, calculations can be performed that are impossible to keep in the mind all at once. A diary allows you to recall what you had for breakfast today ten years ago, which is far beyond most people’s memories. To say nothing of more sophisticated gadgets, like calculators, computers, or smartphones.

Clark and Chalmers substantiate their thesis by discussing the case of Otto, who has Alzheimer’s disease, and for whom a notebook acts like a kind of cognitive prosthesis: it is not too difficult to imagine that, as long as Otto has access to his notebook, he could perform much in the same way as he did before cognitive deterioration started to set in. Concretely, they posit that he navigates a museum together with Inga, whose cognitive faculties are unimpaired. Both find their way equally well; the only difference is that Inga’s memory is processed internally, while Otto relies on an external aid.

That this should be possible in principle follows from the idea of substrate independence. It seems exceedingly chauvinistic to claim that mind could only exist within the sort of neural circuitry that constitutes human gray matter. What if we eventually encountered aliens that use some different machinery for their cogitation? Should we consider them barred from club conscious just on principle? This does not seem a reasonable stance. Rather, whatever fulfills the same role that neural circuitry does in our case should do just as well. But then, why not a notebook? Read more »

A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released