by Scott Samuelson

The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room. —Blaise Pascal

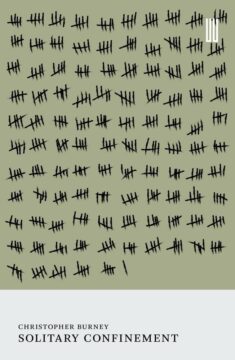

In its “Recovered Books Series,” Boiler House Press has just republished Christopher Burney’s Solitary Confinement, originally released in 1951, a profound, steely, and even sometimes funny account of the five-hundred and twenty-six days the author spent in a Nazi prison cell during World War II. Ted Gioia, who’s written a preface to the new edition, calls it “one of the great masterpieces of contemplative literature.” Even though I’ve made a point of exploring the masterpieces of contemplative literature, I hadn’t heard of Solitary Confinement until a few weeks ago. Given its publishing history, it seems that the book’s fate is to be praised as a masterpiece (by luminaries like Roberto Calasso and Frank Kermode), fall immediately into oblivion, and then be rediscovered a decade or so later—only to go through the same cycle all over.

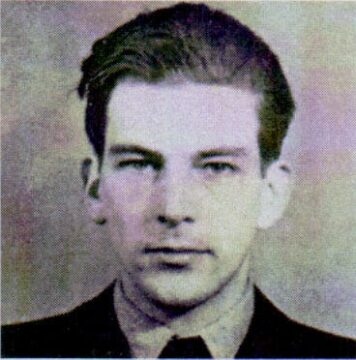

The backstory of Solitary Confinement has the makings of a good movie. Christopher Burney (1917-1980) was born in England to upper-class parents, spent part of his childhood in India, dropped out of school at the age of sixteen (shortly after his beloved father keeled over from a heart attack around the tea table), and then wandered around Europe for a few years picking up languages. Because Burney had learned to speak French idiomatically without an accent, the British army enlisted him as a secret agent during the war. Blind-dropped into occupied France, he made his way to a crew of fellow operatives to disrupt German supply lines. When it was discovered that a double agent had infiltrated his group, Burney attempted to flee to Spain with the Nazis in hot pursuit. Surprised in his sleep by Abwehr agents who were tipped off by a hotel clerk, he was thrown into solitary confinement at Fresnes Prison in the south of France.

His cell was just ten feet long by five feet wide. The space was mostly taken up by a bed and a small table, which he turned on their side during the day to do exercises and walk back and forth.

During his year and a half in the prison, he communicated with practically no one. A few times he was interrogated and tortured. Occasionally fellow inmates tried to tap out words through the walls or shout messages through their slim windows at night. But Burney avoided communicating with them—at first because he was leery that they could be informers and eventually because he’d worked out a successful routine of solitude that he worried would be irreparably broken by any variation.

Burney’s waking hours split into two halves. There was the time from waking until the day’s food arrived: a roll’s worth of bread, a thin slice of liver sausage or a cube of cheese, and a bowl of cabbage in its watery broth. Then there was the time until he could go to sleep. His big decision each day was whether to keep the bread untouched until the evening or to eat it with the weak soup for a close equivalent to a full meal. In his beloved France, it was “hard to think of other things than omelettes, Beaujolais, and Brie.” He observes, “I soon learned that variety is not the spice, but the very stuff of life.”

To deal with the barren stretches of alone time, this high-school dropout reinvented for himself the liberal arts, the arts of freedom. Every evening he treated himself to a concert of whistled tunes: martial songs to fortify his spirit and nostalgic melodies to make him shed a tear for home. The rest of the day he paced and pondered the central questions of death, happiness, time, and eternity.

He wondered if any conception of God could be reconciled with his “pan of putrid soup.” He weighed if “the secret of living in prison, and perhaps of all living, is to dream of pleasant things when there are none real to be enjoyed, and to make the most of the few real pleasures.” He speculated about language and its relationship to the great realities: “There is no one concept of love, however many symbols may be invented for it . . . Poets mirror love roughly in refractory words; philosophers skirt round it in wide detours; and if more lyrics have been sung than doctrines expounded on it, that is no doubt because lyrics are brief and pleasing and doctrines interminably long.”

Occasionally, the guards handed him a scrap or two of paper to wipe himself with. One day the ration was the last few pages of a book on Planck’s Constant. Though Burney had no training in physics, weeks of constant meditation eventually revealed the mathematical argument.

In late spring he was allowed outside for a few minutes, and the reality of the earth overwhelmed him: “Best of all was the careless way of the growing grass, short here, long there, facing in all directions, and with dandelions spreading darker patches waywardly where their seed had dropped . . . ‘I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,’ said Whitman.”

When I read Burney’s comparison of his mental life to “the stone of Sisyphus,” I had to reconsider Albert Camus’s conclusion to his essay on the mythological figure who must always push a heavy rock up a mountain only to watch it roll down: “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Here’s what Burney says he learned from his experience in solitary confinement: “I knew that so many months of solitude, though I had allowed them to torment me at times, had been in a sense an exercise in liberty. For, by absolving me from the need either to consider practical problems of living or to maintain the many unquestioned assumptions which cannot conveniently be abandoned in social life, I had been free to drop the spectacles of the near-sighted and to scan the horizon of existence.”

What can we learn from Burney’s experience? How can those of us who haven’t had to endure solitary confinement get past clichés of “There but for the grace of God go I” and “I wonder if I could handle that”?

Like Boethius in a similar situation, Burney comes to reject strict dichotomies between good and evil, freedom and imprisonment. He finds them untrue and unhelpful: “Life is not a gloomy and impossible grey, as moralists would have it, to be sorted into black and white: all its aspects form a spectrum, of which the greater part is hidden to a single pair of eyes . . . the tiniest window bringing light will always dominate the bleak and oppressive walls and the dangerous passages beyond them.”

Though freedom and imprisonment, good and evil, and so on, are opposites, they’re not absolute opposites. Not only does darkness depend conceptually on the light, it contains a shining seed in its darkest dungeon, and that light is what is real. In the depths of his solitary confinement, Burney isolates a vision in which “pessimism becomes optimism, and the good of life is no longer overshadowed by its imperfections.”

The lesson, which all of us must rediscover again and again, is that we need to stay in touch with the shining arts of freedom—gratuitous activities like music, math, and contemplation—or else we’re prisoners of whatever environment we find ourselves in, even if we have at our disposal all the omelettes, Beaujolais, and Brie in the world.

Though Solitary Confinement deals strictly with Burney’s time in Fresnes, after seventeen months in that hellhole, he was delivered to another nightmare—to Buchenwald, where he managed to stay alive for another year and a half, until the camp’s liberation by the American army on April 12, 1945. Unless we can stop the degradation of our humanity into a bundle of functions and confected identities, as Christopher Burney writes elsewhere, “it will mean back to Buchenwald for me and a maiden trip for most of you.”

***

Scott Samuelson holds a joint appointment at Iowa State University in Philosophy & Religious Studies and Extension & Outreach. He’s the author of three books: Rome as a Guide to the Good Life, Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering, and The Deepest Human Life—all published by the University of Chicago Press.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.