by David J. Lobina

‘Philosophy is a prolonged meditation on death’, so starts what may well be Mark C. Taylor’s 35th book, After the Human. A Philosophy of the Future, published by Columbia University Press. I must admit that I didn’t know Taylor’s work before reading this book, though this is perhaps unsurprising, as for most of his career Taylor seems to have focused on the study of topics and thinkers that are not particularly close to my own interests. This remains somewhat the case in After the Human: there is some discussion of Descartes and Kant – so, yea! – but there is far more of Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Derrida – a big nay.

At the same time, Taylor devotes the bulk of his book to arguing that cognition is widespread in the world, from humans and other animal species to even plants and computer programmes, and all things cognitive are clearly up my street (by cognition Taylor means information processing tout court; more below). And yet most of the discussion keeps coming back to Hegel and co., even though most of the evidence, and some of the arguments, pertain to cognitive science proper and engaging with some of the contemporary literature in the philosophies of psychology and cognitive science would have been more fruitful considering the final result on display. I think this constitutes a missed opportunity.

I also think that in the end the book fails to deliver what it promises – a philosophy of the future – and instead God sneaks up on us quite unexpectedly at the very end, for no apparent reason (I should add that religion is one of Taylor’s areas of expertise, though it doesn’t feature all that much in the book). Before getting to the actual contents of the book, though, I would say that the volume could have done with a different style of argumentation.

The book is fairly eclectic, with various personal recollections intermixed with plenty of long quotes from a great number of thinkers and scholars. It is quite hard to keep up with, and keep track of, Taylor’s myriad references, points, and asides, and the presentation clearly could have benefited from a bit of signposting (oddly enough, though, the book is quite repetitive at times). In addition, and this may well be a personal shortcoming, I fear I missed out on a number of important points here and there, especially in relation to the many quotes from Hegel and company. I didn’t feel like a great many of these quotations helped the reader much or were added for the elaboration of a particular argument, but rather they were in there for exposition purposes and one needed to be acquainted with the ideas referred to already in order to understand them – and to understand how they fit in within the overall story Taylor wants to tell. As a case in point, Hegel’s distinction between Either-Or and Both-And makes an appearance at various points in the book (on page 60 Either-Or is related to understanding and Both-And to reason), but I really don’t know what this actually means or what the significance is. Granted, I have never really understood Hegel, Heidegger or Derrida all that well, but I am pretty sure that they are not a good fit when it comes to the study of cognition. A final point about style: the book contains many statements expressing rather strong opinions, but these are rarely ever spelled out properly or indeed argued for, but instead are often simply offered as statements of fact (some below!).[i]

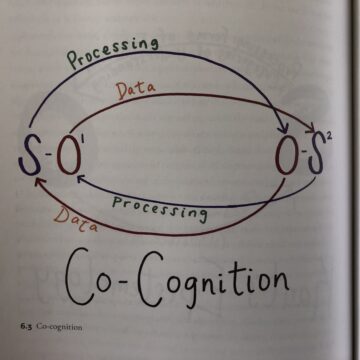

All that aside, I think it is a fair characterisation to say that there are two main ideas or running threads in the book: radical relationalism and pan-cognitivism. I have already alluded to the latter – namely, the claim that information processing is ubiquitous in nature – and I will come back to this properly below. Regarding radical relationalism, this is first introduced in the preface, where it is described, in typical fashion, as a situation ‘in which divisive oppositions and conflictual activity give way to codependendence [sic] and coemergent [sic] symbiosis where everything becomes itself in and through the probabilistic entangled play of differences’ (p. xii). This is later exemplified as a self-organising and self-maintaining network of networks (pp. 13-14), a nexus (styled as neXus in the text, roughly) of reciprocal interrelations among parts and whole (p. 59). Everything is related, one might say, and Taylor sees many parallels all over nature in terms of networks of networks.

This starts in Chapter 1, where Taylor discusses the four basic elements of earth, water, air, and fire, which are shown to be all connected in a hand-drawn graphic, the latter a constant in the book (as in the photos attached here). Chapter 2 introduces some key notions to be explored throughout the book, such as Descartes’s dualism, the culprit of many things to denounce in what follows, though experts on Descartes will no doubt demur Taylor’s interpretation of Cartesian philosophy. Towards the end of the chapter, Taylor anticipates that in later chapter he will show that cognition extends to the physical, plant, animal, and artificial realms too (the word artificial almost always appears within scare quotes). Chapter 3 is devoted to relationalism, where the dualistic world that started with Descartes and culminated with Kant (mind/body, but also cogito/world, human/nonhuman) is appraised to be ontologically mistaken, epistemologically misleading, and ethically corrupt (p. 70), though there is little in the way of elaboration.

Chapter 4 is entitled Relativity and discusses physics, including Einstein’s theories, as well as the relationship between time and space, deriving some relevant philosophical conclusions from this, though the discussion would have welcomed the input from modern scholars in philosophy of physics – some of the quotations Taylor uses are old philosophical musings from long-deceased physicists, and some of these views are not only dated but have been superseded in various ways (oddly, but as is the case throughout the book, the chapter starts with St. Augustine and then moves on to Hegel and Derrida; Hegel’s relationalism, Nietzsche’s perspectivism, Heidegger’s originary temporality and Derrida’s becoming-time-of-space are all said to be relevant concepts here, but these went mostly undefined). Chapter 5, for its part, is focused on quantum physics and some further philosophical elaborations from the likes of Bohm and Heisenberg are discussed.

Cognitive matters start properly in Chapter 6, where Taylor discusses information processing, starting with seminal works by Alan Turing on computability theory and Claude Shannon on information theory, and here too Descartes is criticised once again, this time for eliminating mind from matter as a result of what Taylor calls Cartesian anthropocentrism (p. 155); and it is here that pan-cognitivism is laid out: not everything in nature is conscious, in contrast to panpsychism (pp. 176-99), a concept that is discussed seriously in contemporary philosophy, though it remains a peripheral position, but everything is cognitive in the restrictive sense that information processing is ubiquitous in the world, and this on account, once again, of Hegelian relationalism, relational quantum mechanics, relativity theory, and different aspects of information theory (p. 179). But not a cognitive science idea in sight.

Chapter 7 moves to cognition (ergo, information processing) in ecological systems, and Taylor here draws from Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, first, and on work by Richard Lewontin, later on, eventually making the point that quantum ecology is radically relational too and cognition-so-understood is distributed throughout physical and biological systems. Chapter 8 moves to biological systems, with and without a nervous system, and in the event Taylor spends much time discussing information processing in the immune system. Chapter 9 starts with the admonition that ‘there is no longer any doubt that cognition can even occur in organisms that have neither a brain nor a nervous system’ (p. 238; not sure this was demonstrated in previous chapters at all) and then purports to show that cognition-as-information-processing is part and parcel of plant systems as well as of non-human animals – in the form of carbon transfer between plant species, in the case of the former, though there’s supposed to be plenty of perception, memory, learning, and decision making going on too, and in the form of interspecies communication, in the case of animals (Taylor makes use of Paco Calvo’s work on plant cognition, an actual cognitive scientist).

Chapter 10 is devoted to Artificial Intelligence, where we are told that machines are becoming more like people and people more like machines (p. 279), though in the event the chapter argues that the Intelligence Amplification (IA) of humans through the use of technology is more likely than the advent of a general Artificial Intelligence (AI). Are humans the last stage of evolution, Taylor asks at one point, as he considers the possibility of human-AI symbiosis (p. 311) towards the end of this chapter.

The last chapter presents a graphic representation of the neXus graphic (p. 341) and ends with the following, rather cryptic reflection:

As I have been arguing, we are plagued by oppositional ideologies in a radically relational world. The will to mastery ends with a solipsistic world in which everywhere man (sic) [sic!] turns, he sees only himself. To break out of the prison house of human exceptionalism and insidious individualism, it is necessary to apprehend ourselves as parts of something larger than ourselves. Another name for the eventful process of “the arising and passing away that does not arise and pass away” is God, and another name for its radical relationality is love…amor mundi (p. 342).

What’s God got to do with any of it?

Put that to one side and let us come back to the issue of the study of cognition, which in turn will allow me to pick up a couple of spurious arguments from the book to boot. As mentioned earlier, Taylor makes little use of the extensive cognitive science literature, and this is to the detriment of his account.[ii] If nothing else, it would have provided Taylor with a more robust understanding of what cognition or intelligence involve according to cognitive science.

One reoccurring complaint in Taylor’s book is that cognition or intelligence are understood too narrowly in philosophy (no references provided, though), to the point that these are notions that are only applied to human beings, whereas these concepts need to be understood in a more expanded way – and, hence, cognition as information processing. This may well be a matter of interpretation, but for me it is the cognition-as-information-processing definition that is much too narrow and not an expanded concept at all. After all, information processing is one part of the story of what cognition is, and most information-processing accounts in cognitive psychology are not akin to Shannon’s information theory in any strict sense – the work of both Turing and Shannon inspired the birth of cognitive science, but their accounts are not ipso facto theories of cognition.

Take Jerry Fodor’s work, a figure inexplicably absent in Taylor’s book, for no other philosopher or cognitive scientist has done more to defend the thesis that cognition, including animal cognition, can be studied in terms of computations over structured representations. The key here lies on the kind of mental representations a given species possesses as well as the operations and computations carried out over such representations, both of which are matter of investigation. Sometimes called the language-of-thought account of cognition, scholars such as Fodor have always supported the idea that the general theory is probably applicable to all animal species, though different species will have their own language of thought – after all, the mental representations (often called concepts) humans make use of are rather different from the concepts of other animal species, and this is also likely to be true of the computations available to each species.[iii]

A computational theory of cognition can also be applied to many other phenomena; Taylor spends some space discussing the work of Niels Jerne on the immune system in chapter 8, but fails to note that an important influence on Jerne happened have been Noam Chomsky’s generative theory of language, which is of course also a computational theory of cognition (Chomsky appears one time in Taylor’s book, where he is somewhat bizarrely described as a structuralist). Crucially, though, all these computational theories – of human cognition, of non-human cognition, of language, of the immune system, etc. – are all different in kind and not isomorphic in any strong sense, and this is not surprising – this is expected considering the different evolutionary histories of each phenomenon.

At times in the book Taylor appears to explicitly reject this view, stating that human thinking emerged from cellular, plant, and animal forms of cognition (p. 280), which might well explain the later musing regarding whether humans constitute the last stage of evolution. But this is to misunderstand how evolution works and such questions simply do not apply.[iv] True, all life forms emerged from the same ancestor if you go back in history far enough, but there is no linear structure in evolution, as different species diverged from each other over a rather long time, and thus evolved along different paths that produced not only different phenotypes (the physical characteristics of a species, many of these observable), but also different cognitive systems. Human beings (homo sapiens), for instance, are a distinct species within the hominid family of primates, a family which diverged from other mammals 85 million years ago, with the Homo genus diverging from other primates around 8 million years ago. As a consequence, the cognitive systems of humans can’t but be rather different from the cognitive systems of other animal species.

As stressed, this is not deny that the same kind of theory may well be employed to account for large parts of the cognition of many animal species, and even phenomena such as the immune system, but the scope of the theory shouldn’t be exaggerated or the analogies stretched too much. We know full well that many organisms are both sentient and sapient, where intelligence can be described as the ability to demonstrate complex behaviour conducive to reaching specific goals (a common definition of intelligence in cognitive science), and we also know that this often follows from the fact that in such cases the relevant information processing is based in electrochemical information flows where electrical signals are converted to chemical signals (neurotransmitters) and then back to electrical signals. But the language-of-though account has certain limits of application, and these do not extend to plants and computer programmes (on AI, I have discussed these issues extensively here, here, and here, where I lay out many more of the properties involved in cognitive processes).

Taylor often complains of anthropocentrism in the book, but anthropomorphism is perhaps more serious a shortcoming, and there is a fair amount of that too in his work. It would have been better for Taylor to engage with cognitive scientists and modern philosophers of cognitive science a bit more and leave his usual accomplices to one side on this occasion. Or in other words, less Hegel and Derrida, and more Chomsky and Fodor!

[i] Another problematic issue here is that Taylor likes to employ etymology to make a point or support an argument, but not only does he get the etymology wrong too many times (the word “human” does not come from Latin humus and the word “speculation” does not come Latin speculum), moreover etymology doesn’t really establish the current meaning of words (usage does) or indeed how a concept ought to be understood at all.

[ii] Taylor mentions the philosopher David Chalmers when talking consciousness, but discusses his work not at all. Chalmers, along with Alex Clark, would have been useful when approaching the issue of Intelligence Amplification, for instance – Clark’s theory of extended cognition is a prominent topic in cognitive science and would have served Taylor well. I’m of course glad he didn’t, though, so I don’t have to explain what’s wrong with the extended mind view.

[iii] Another inexplicable absence from Taylor’s book is the burgeoning field of animal cognition in chapter 9, instead focusing on so-called ‘deep listening’ and the dubious claim that there is any significant interspecies communication, along with the unsupported and baseless claim that AI algorithms are to make interspecies communication a reality (p. 255). The oppositive view – say, that there is likely to be little to no interspecies communication – Taylor calls interspecies solipsism, but this is a misunderstanding of evolutionary history, as I discuss in the text.

[iv] I pass over in silence Taylor’s claim that whatever humans create, in this case AI (a computer programme), becomes part of an ongoing inter-evolutionary process (p. 280), with the corollary that AI is just another form of alternative intelligence (and, hence, his insistence in writing artificial intelligence within scare quotes, for there is nothing artificial about it as far as he is concerned).

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.