by Mary Hrovat

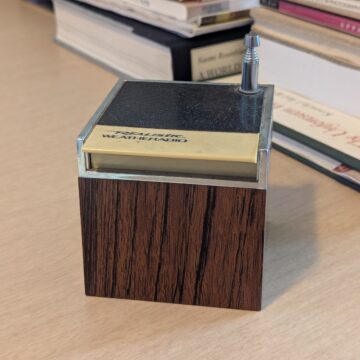

After my power went out during a recent round of severe storms, I turned on my battery-operated Realistic Weatheradio. I bought this cubical radio at Radio Shack many years ago, and it sits on a bookshelf in the living room, largely ignored until extreme weather happens along. It can be tuned to one of two wavelengths on which the National Weather Service broadcasts a loop of information on current and predicted weather conditions. It has a large, obvious on-switch; the two dials on the bottom are labeled “Tuning” and “Volume.”

When I turned the radio off after the storms had moved on, it occurred to me that it would probably look very old-fashioned to young people; I was thinking of my grandchildren and nieces and nephews. The sides are covered in wood veneer, a nod to the fact that radios used to be pieces of wooden furniture. I wondered if anyone else still uses a radio that you tune with a dial. For some reason, the radio was defamiliarized so that even to me it seemed to be slightly out of place in time. (I feel that way myself sometimes.) And it unexpectedly conjured an entire lost world.

I looked up the Weatheradio and learned that it was sold between 1982 and 1992. Realistic was a house brand of Radio Shack, which for many years sold consumer electronics. It was a standard fixture of malls in my youth, like Orange Julius and WaldenBooks. In 2015, the company declared bankruptcy, in part because it couldn’t compete well as the market for electronics—in fact, the nature of consumer electronics—changed dramatically. It changed hands several times and is currently an online business called RadioShack (losing a space in its name, among many other things). The only actual radios it currently sells are four models of a vintage three-band radio (AM, FM, shortwave). (So I guess there are other people who tune their radios using a dial.) It’s a familiar story, and it encapsulates one of the ways the world has changed in my lifetime.

I can’t remember when I bought my radio, but my life has also changed considerably since the decade it was on the market. Seeing the weather radio as a vintage object brought home to me how many things that used to be familiar have vanished. I don’t miss Radio Shack, or malls, and I don’t particularly mind that some of the more recent technology I use is now considered vintage. But sometimes it feels as if the world has moved on and left me behind. I’ve always been a bit of an oddball, but the world I learned to adapt myself to was the one I grew up in, and that world is largely gone.

∞

I’m not sure why the radio suddenly seemed like a time traveler to me. I have many old things in my house, and the house itself is 60 years old. I’m a bit older than that. It shouldn’t be surprising that I own things that were made and obtained under conditions that were very different from the way life is now. But for some reason, when I put the radio back on its shelf, I thought of it not as something that I’ve had for a long time, but as something that had traveled down through time with me.

Why down, I wondered. Our culture tends to think of the past as extending behind us and the future as stretching out into the distance ahead. I sometimes imagine time as more complicated than that, but it seemed strange to think of moving downward toward the future. But then I remembered that we do talk about things being handed down from one generation to the next. Family trees run from the top to the bottom of the page. We imagine people passing names, genes, and physical features down through the generations. Maybe that’s why I thought of moving down through time.

Other things that are passed down include valuable objects: houses or heirloom possessions of one sort or another (the family silver), in wealthy families, but also mementos, small things—cookie jars, say, or prayer books—that have stories attached. So I started thinking about things that had traveled down through time to me, some of them from eras that I didn’t live through.

For example, I have a cigarette lighter that my mother gave my father for Christmas when they were dating. I hadn’t even known that it existed until 10 or 15 years before my father died, when he wrote about it in a series of informal reminiscences, and I don’t remember ever seeing it. But during the 18 years I lived with my parents, I traveled through time with it (or it with me), and it re-entered my life when one of my brothers sent me a box of small treasures of family history after my father died.

Because I buy a lot of used books, many of them have come down to me from unknown hands. You could say that they make their way down through time to me and travel with me for a while. Someday, I hope, they’ll be handed down to others after I’m gone and carried into a future I won’t know. What if there were something like genealogical charts for books—the physical books, not the authors and the people who influenced them, and not just the rare or precious books—so that you could trace a book’s descent down a lineage of owners?

∞

That mental image of moving down through time with the weather radio also had a vague physical sense to it: a rather odd impression of moving through the dark, buffeted by bursts of light and sound. That struck me as a peculiar sense of time.

I wonder if I was thinking of both personal and national history, and the way that events and problems sometimes seem opaque even when you’ve lived through them, or lived with them for a long time. In some ways, the world and my life seem more understandable as I grow older, but in other ways they seem more mysterious and random. At any rate, although the idea of things being passed down explains the sense of traveling downward through time, nothing about it captures this uneasy sense of traveling down through uncertainty and strangeness.

There’s another sense of time that might be related to that sense, though; we also speak of time as a river, flowing into the future and carrying us downstream. Four years ago, I wrote about the river of time in the context of my sister’s death. Although the first two or three days after she died seemed very long, I also had an acute sense of time rushing me into the future without her, forcing me to leave her behind.

Personal time and historical time sometimes seem like a broad slow river carrying people gently through scenery that doesn’t change much from day to day. But in times of loss, or of rapid change, the river of time feels more like a series of rapids. I wonder if my sense of moving through a dark strange passage is related in part to the current sense of watching our country being reshaped, with results that we expect to be devastating but cannot fully predict or understand, and with little idea of how the crisis might be resolved.

The sense of a dark strange journey also returns me to the sense of how poignant it is to live through the transformation of the world into something else. Vintage now means not the things of my grandparents or parents, but the things of my youth; well, it was bound to happen if I lived long enough. But growing older also means slowly losing connections with people who lived through much of the same time that I did, people who knew the ones I love who have died, people who remember all the ways that life used to be and is no longer. This is also inevitable, but harder to take.

∞

You can see more of my work at MaryHrovat.com.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.