by Scott Samuelson

The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room. —Blaise Pascal

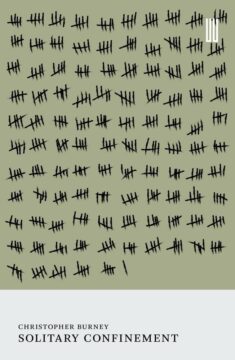

In its “Recovered Books Series,” Boiler House Press has just republished Christopher Burney’s Solitary Confinement, originally released in 1951, a profound, steely, and even sometimes funny account of the five-hundred and twenty-six days the author spent in a Nazi prison cell during World War II. Ted Gioia, who’s written a preface to the new edition, calls it “one of the great masterpieces of contemplative literature.” Even though I’ve made a point of exploring the masterpieces of contemplative literature, I hadn’t heard of Solitary Confinement until a few weeks ago. Given its publishing history, it seems that the book’s fate is to be praised as a masterpiece (by luminaries like Roberto Calasso and Frank Kermode), fall immediately into oblivion, and then be rediscovered a decade or so later—only to go through the same cycle all over.

The backstory of Solitary Confinement has the makings of a good movie. Christopher Burney (1917-1980) was born in England to upper-class parents, spent part of his childhood in India, dropped out of school at the age of sixteen (shortly after his beloved father keeled over from a heart attack around the tea table), and then wandered around Europe for a few years picking up languages. Because Burney had learned to speak French idiomatically without an accent, the British army enlisted him as a secret agent during the war. Blind-dropped into occupied France, he made his way to a crew of fellow operatives to disrupt German supply lines. When it was discovered that a double agent had infiltrated his group, Burney attempted to flee to Spain with the Nazis in hot pursuit. Surprised in his sleep by Abwehr agents who were tipped off by a hotel clerk, he was thrown into solitary confinement at Fresnes Prison in the south of France.

His cell was just ten feet long by five feet wide. The space was mostly taken up by a bed and a small table, which he turned on their side during the day to do exercises and walk back and forth. Read more »