by Katalin Balog

It was the first day of a Tibetan Buddhist retreat in 2016. We were about to participate in a ritual of chants and burning sage. Before we proceeded outside, the head teacher asked all of us to invite someone we would like to share this moment with. Instantly and vividly, my grandfather appeared in my mind. I found the defiance embodied in this choice shocking. My grandfather was the rock of my childhood. Kind, optimistic, a fountain of knowledge about the world, a lover of poetry and music, he was the undisputed authority in the family. He was a heir of the Enlightenment, and he would have been horrified by my association with religion, even the nontheistic Buddhist variety. At that moment, I realized that when the chips were down, I would choose my Enlightenment heritage over the enlightenment Buddhism promised. I was at this retreat (and later joining a synagogue) in an effort to recover parts of my soul that my secular rationalist upbringing made me feel I was missing. My being here was my rebellion against this very Enlightenment heritage.

But once here, feelings of unease increased with every chant about the “basic goodness” of humans, with every question waved away with impatience, with every forced debate on topics the leader of the organization set for his ostensibly grown-up disciples, with the disapproving jibes about “too much thinking”. The dissonance became too much, and by the end of the retreat – six long weeks later – I was out, no longer a disciple.

The tension I was experiencing was a small manifestation of the central problem of modernity. Can the common-sense, first-person, subjective view of ourselves as souls or subjects be reconciled with a scientifically informed, objective perspective? Can reason be overridden in the name of mindfulness, of systematic attention to subjective experience? This question preoccupied two very different thinkers of the 19th century, Auguste Comte and Søren Kierkegaard, who, though they seem to have been unaware of each other, lived at the same time and have come to very different conclusions. Read more »

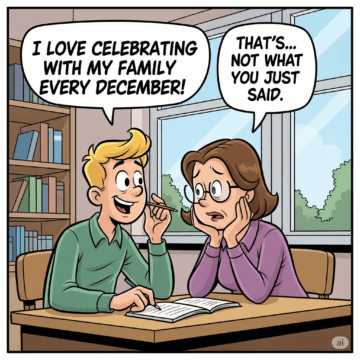

At a Christmas market in Germany, I told my German girlfriend’s mother that I masturbate with my family every December.

At a Christmas market in Germany, I told my German girlfriend’s mother that I masturbate with my family every December. The File on H is a novel written in 1981 by the Albanian author Ismail Kadare. When a reader finishes the Vintage Classics edition, they turn the page to find a “Translator’s Note” mentioning a five-minute meeting between Kadare and Albert Lord, the researcher and scholar responsible, along with Milman Parry, for settling “The Homeric Question” and proving that The Iliad and The Odyssey are oral poems rather than textual creations. As The File on H retells a fictionalized version of Parry and Lord’s trips to the Balkans to record oral poets in the 1930’s, this meeting from 1979 is characterized as the genesis of the novel, the spark of inspiration that led Kadare to reimagine their journey, replacing primarily Serbo-Croatian singing poets in Yugoslavia with Albanian bards in the mountains of Albania.

The File on H is a novel written in 1981 by the Albanian author Ismail Kadare. When a reader finishes the Vintage Classics edition, they turn the page to find a “Translator’s Note” mentioning a five-minute meeting between Kadare and Albert Lord, the researcher and scholar responsible, along with Milman Parry, for settling “The Homeric Question” and proving that The Iliad and The Odyssey are oral poems rather than textual creations. As The File on H retells a fictionalized version of Parry and Lord’s trips to the Balkans to record oral poets in the 1930’s, this meeting from 1979 is characterized as the genesis of the novel, the spark of inspiration that led Kadare to reimagine their journey, replacing primarily Serbo-Croatian singing poets in Yugoslavia with Albanian bards in the mountains of Albania.

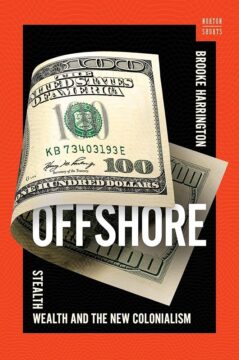

The Paradise, Pandora and Panama Papers, exposing secret offshore accounts in global tax havens, will be familiar to many. They are central to the work of economic sociology professor, Brooke Harrington. She has spent many years researching the ultra-wealthy and several books on the subject have been the result. Her latest book Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism is a continuation of her research; it focuses on ‘the system’, the professional enablers who support and advise the ultra-wealthy and make it possible for them to store and conceal their phenomenal fortunes in secret offshore accounts.

The Paradise, Pandora and Panama Papers, exposing secret offshore accounts in global tax havens, will be familiar to many. They are central to the work of economic sociology professor, Brooke Harrington. She has spent many years researching the ultra-wealthy and several books on the subject have been the result. Her latest book Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism is a continuation of her research; it focuses on ‘the system’, the professional enablers who support and advise the ultra-wealthy and make it possible for them to store and conceal their phenomenal fortunes in secret offshore accounts.

Sughra Raza. Light Tricks, Seattle, March, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Light Tricks, Seattle, March, 2022.

I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in

I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in  At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.

At about 6:30 am, we pulled up to the Labor Ready office in the Central District. My friend – who for the sake of this column will be called Rick – and I were responding to a trespassing call: a woman who was asked to leave the day-labor agency office was refusing.