by Eric Schenck

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

One of my New Year’s resolutions was to read one of the “classics of fiction” each month this year. I’m happy to report that I’m on pace to succeed.

While I won’t tell you which books I’ve read so far (no spoilers here!) this year of reading has taught me a few things.

I used to think it was a waste of time reading old novels. But now?

I realize it can actually teach you quite a lot – even if it’s not what you expected. In honor of the nine classics I’ve read so far in 2025-

Here are nine reasons you should read them in the first place.

1) You can get off the self-help train.

I used to read self-help books almost constantly. Whether it was about optimizing your time, optimizing your health, or optimizing your optimization (sadly, not a joke), I was trying to get to the ideal level of everything.

But if you really want to improve your life – the classics will help.

Stories like this teach you lessons on love, death, success, and what it means to be human.

What more do you need?

2) You can hate on the classics you don’t like.

I said there wouldn’t be any spoilers here, but I can’t help myself. Don’t hate me for what I’m about to say…

But I read “Beloved” by Toni Morrison and I couldn’t stand it. Too poetic. Plus, you’re telling me a ghost came back to live with her and everybody was cool about it?

Pssssssh.

There’s a special kind of club (even if you’re the only member) where you hate a book everybody else seems to love.

And with the classics?

That club is all the cooler. Read more »

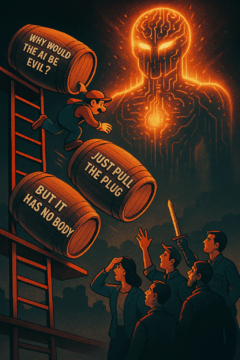

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

As AI insinuates itself into our world and our lives with unprecedented speed, it’s important to ask: What sort of thing are we creating, and is this the best way to create it? What we are trying to create, for the first time in human history, is nothing less than a new entity that is a peer – and, some fear, a replacement – for our species. But that is still in the future. What we have today are computational systems that can do many things that were, until very recently, the sole prerogative of the human mind. As these systems acquire more agency and begin to play a much more active role in our lives, it will be critically important that there is mutual comprehension and trust between humans and AI. I have

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity.” — Ben Bernanke

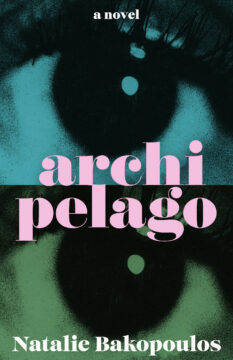

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

Natalie Bakopoulos: Thank you so much, Philip, for starting this conversation, and for these wonderful observations and connections. You’re absolutely right, I was indeed playing with the idea of “beginnings.” “Here in Greece,” the narrator says, “the rivers rarely have a single source: They spring from the mountains at several places.” I also wanted to think about the arbitrariness of origin and a way of thinking about belonging that wasn’t necessarily about “roots”—but instead rhizomes, as Edouard Glissant, and others, might say.

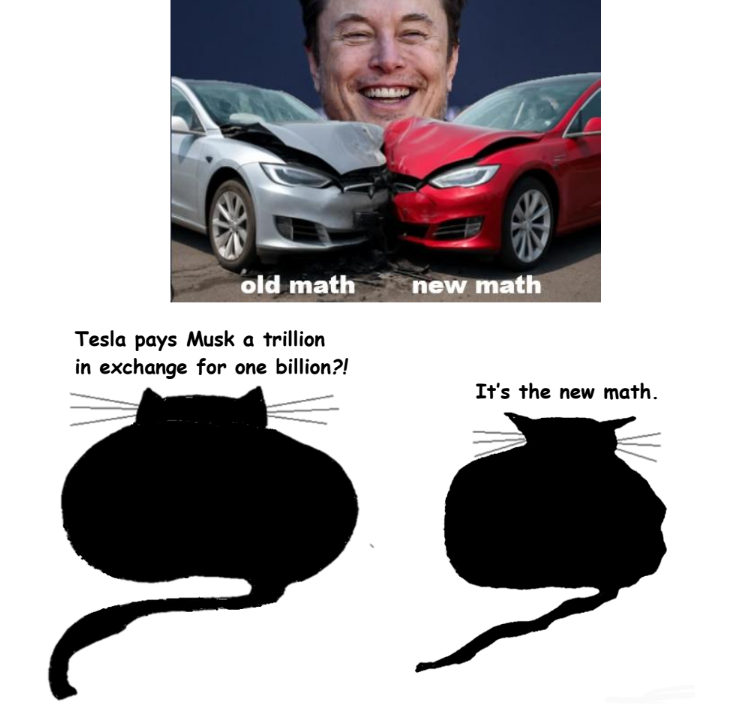

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

In

In