by Sherman J. Clark

In a recent essay, Don’t Be Cruel, I argued that looking away from cruelty—mass incarceration was my example—comes at a cost. The blindness and mental blurriness we cultivate to avoid discomfort also stunts us. Avoidance may feel like self-protection, but it leaves us less able to flourish. It is hard to find our way in the world when we are self-blinded. Facing hard truths, including cruelties in which we are indirectly complicit, can be a form of ethical weight training—bringing not just sight and insight but ethical strength.

In a recent essay, Don’t Be Cruel, I argued that looking away from cruelty—mass incarceration was my example—comes at a cost. The blindness and mental blurriness we cultivate to avoid discomfort also stunts us. Avoidance may feel like self-protection, but it leaves us less able to flourish. It is hard to find our way in the world when we are self-blinded. Facing hard truths, including cruelties in which we are indirectly complicit, can be a form of ethical weight training—bringing not just sight and insight but ethical strength.

But facing the truth is easier said than done. Because the truth is that our world is rife with horrors: war, injustice, exploitation, racism, rape. Not to mention the corruption, cruelty, and would-be fascism looming in our national life. To confront all this at once would crush us. We recoil not because we are heartless but because we know that knowing more will hurt. Psychologists describe what happens when we don’t avert our eyes. Studies of “compassion fatigue” show how repeated exposure to others’ pain can leave us depleted, even disoriented. Healthcare workers, legal advocates, teachers—those who must confront suffering daily—describe the exhaustion that follows. The problem is not lack of care but its weight: to feel too much, too often, wears down our capacity to respond. We simply cannot see all of it all the time.

Yet this necessity does not remove the cost. The very act of triage—choosing what to attend to and what to ignore—shapes us. We become people who can bear certain kinds of truth and not others. Sometimes that protective instinct is wise; no one can survive without rest. But sometimes it dulls into habit, and habit into incapacity. We find ourselves avoiding not just unbearable horrors but also discomforts we might well endure—and from which we might grow. We are caught in a bind. On one side: cultivated ignorance that seems to let us glide through life but costs us our growth. On the other: overload, the crushing weight of truths too terrible to bear. How do we remain open to what we must know without being undone by what we see?

The difficulty is not only volume. Certain kinds of knowing carry their own dangers. True knowing requires not just information but empathy. Facing cruelty in a way that conduces to ethical growth means not just memorizing incarceration statistics but recognizing human suffering. And that kind of knowing destabilizes us in subtle ways.

To enter another’s world is to blur the edges of our own. Psychologists call this “self-other overlap”: the merging of boundaries when we take another’s perspective seriously. Sometimes this deepens connection; but it can leave us disoriented. Empathy can also distort. We feel more readily for those who are near, familiar, or attractive. One vivid case moves us more than anonymous thousands. This is not a flaw in our compassion so much as a feature of it—but it means empathy, untethered, can mislead. We may confuse emotional resonance with clarity, or feel righteous for “feeling the pain” without addressing its source.

So the problem is not just quantity but quality. Some ways of knowing, even in small doses, can unsettle us or send us astray. Empathy is indispensable to our humanity, but it is also risky. We need not only courage to face what is hard to know, but discernment about how we face it. Read more »

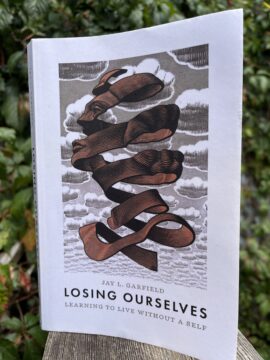

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take