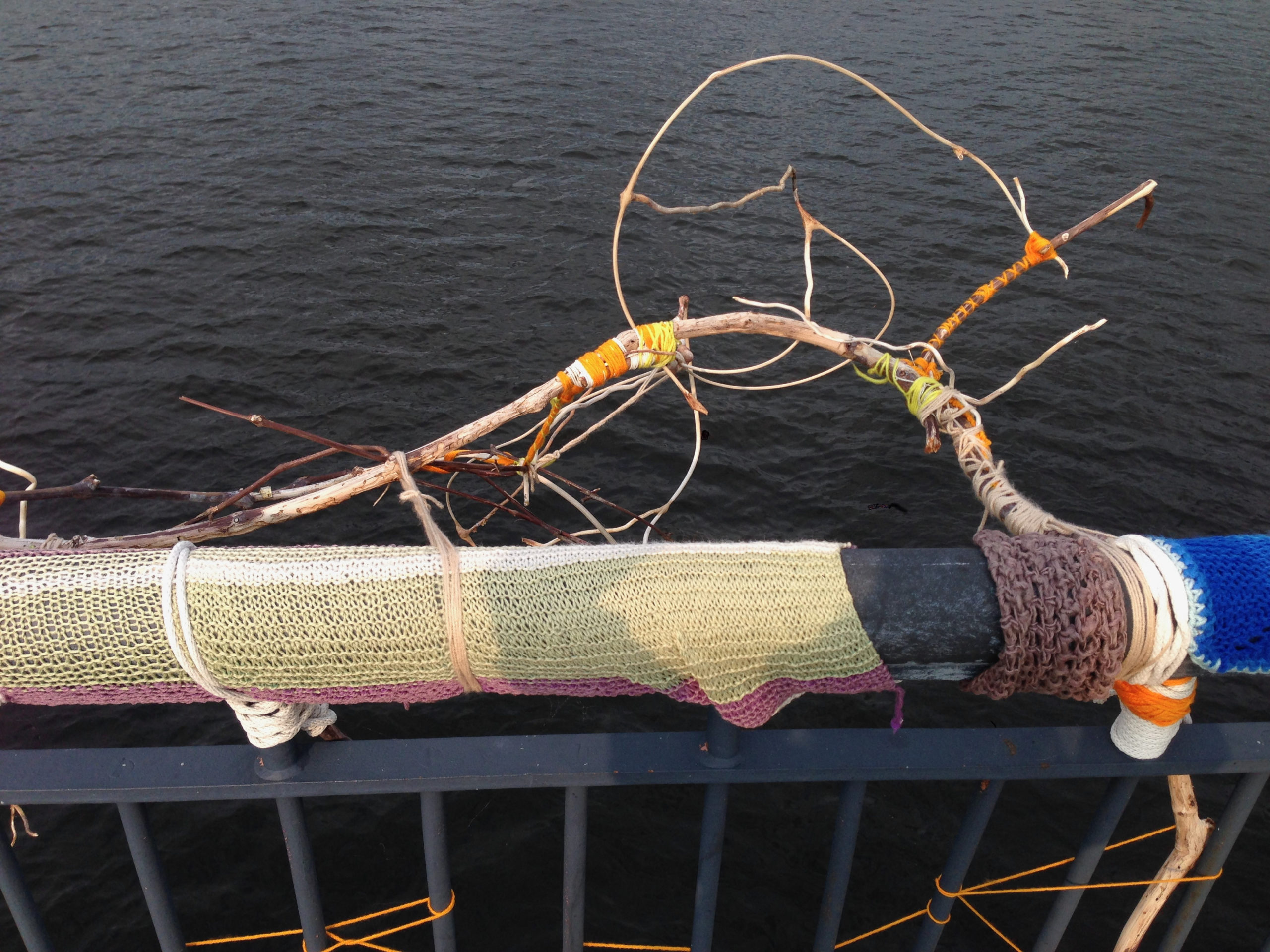

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Digital photograph.

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Digital photograph.

by Rafaël Newman

Every human generation has its own illusions with regard to civilization; some believe that they are taking part in its upsurge, others that they are witnesses of its extinction. In fact, it always both flames up and smoulders and is extinguished, according to the place and the angle of view. —Ivo Andrić (tr. Lovett F. Edwards)

I was accompanied through the last week of October by a succession of Bosnians: Adnan introduced me to Sarajevo; Emir and Senad took me through Eastern Bosnia; Ajla and Merima led me down the valley of the Neretva River to visit the dervish monastery at Blagaj and the reconstructed bridge at Mostar; and Ahmo, the stoical busman employed by Funky Tours, drove me three 12-hour days in a row through the multiethnic heartland of former Yugoslavia.

It was the time of year when I usually accompany my partner, Caroline Wiedmer, a professor of Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies at Franklin University Switzerland, and a group of students on Academic Travel, the extramural component of a semester-long course with an international theme. (I have written about past travels here, here, and here.) “CLCS 220: Inventing the Past,” a course in memory studies Caroline has offered many times since 2007, has typically focused on French, German, and Polish sites of Holocaust remembrance, an early specialty of hers; this year it was devoted to Sarajevo, as well as to other towns in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to a study of the culture of memory there, nearly thirty years after the Dayton Agreement put an end to the violence and atrocities surrounding the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Our daughter, Hella Wiedmer-Newman, was also along on the trip. Her work as a doctoral student in art history at the University of Basel focuses on art and memorialization in postwar ex-Yugoslavia, and this, together with her growing proficiency in the Bosnian language, made her an obvious choice to lead some of the on-site seminars in Sarajevo. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, was originally published in 1995 but more recently updated in a 25th anniversary edition in 2020. Well, he added a new introduction, but no study or concept in the book was updated despite huge changes in our lives since then and tons of new studies with updated technology. It’s kind of refreshing to read a book about the problem with kids today without a single mention of phones, but it feels a little sloppy. Goleman is a science journalist without a clinical practice in psychotherapy as far as I can tell. While his book is about how to be smart according to the front cover, it’s also being used in psychotherapy. It’s a fast, engaging read, but I have some concerns about the content and application.

Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, was originally published in 1995 but more recently updated in a 25th anniversary edition in 2020. Well, he added a new introduction, but no study or concept in the book was updated despite huge changes in our lives since then and tons of new studies with updated technology. It’s kind of refreshing to read a book about the problem with kids today without a single mention of phones, but it feels a little sloppy. Goleman is a science journalist without a clinical practice in psychotherapy as far as I can tell. While his book is about how to be smart according to the front cover, it’s also being used in psychotherapy. It’s a fast, engaging read, but I have some concerns about the content and application.

The book outlines the need for emotional intelligence (EI) to be overtly taught to children, explains the psychoneurology of EI, argues for the primacy of emotional intelligence for success, adds in the need for emotional supports, and ends with a call for parents to be better educated as well. The principle underlying Goleman’s text is that there are four specific domains, adapted from Salovey & Mayer, that emerge from the activity of our brain circuits that have more of an impact on our general well being than does our intelligence: self-awareness, self-management (formerly motivation and self-regulation), empathy, and skilled relationships. Goleman explains that people will be better off emotionally, relationally, and vocationally if they develop their emotional intelligence to identify and understand their feelings as they happen, manage them effectively, understand other people’s feelings, and relate to others more positively. With a calm mind, people can make better decisions, which positively affects all other aspects of their life. Goldman has used these domains to help to develop educational programs to teach children Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) in the schools through the CASEL organization. I feel like it goes without saying that being able to manage our emotional experiences helps in other aspects in our lives, so I’m all in at this point. Read more »

by Gus Mitchell

When we hear the constant cry–that we need “better stories”–there is surprisingly little followup. How or where we are going to find them, how are they going to be told? The “how” is the thing.

Knowledge, our fetishizing of knowledge, our demand that we have an opinion on every new fact makes us utterly helpless, leaves us feeling that we don’t really “understand” any of it at all. Our most constant daily ritual is that of the scroll, the instantaneous return to the temple of information.

In our lack of knowledge and our lack of power, we can at least choose the stories we want to be told. Indeed, we have more choice than ever before. Why then, are we constantly told that our suiciding world’s crisis is “a storytelling crisis?”

Storytelling is a power relationship, a good, beneficial, and safe kind of power. The power is that the storyteller knows something which you do not, and which you want to lean forward to hear, to catch.

Nietzsche’s Last Man has no one to tell him a story. The Last Man is stuck in a world of cold realism, which paradoxically keeps seeming less and less real, less comprehensible.

Is the problem partly that the only civilization we have, which still shrilly declares itself to be the only possible arrangement of things, the last word on a realistic way of living, good or bad, is, in fact, fundamentally fantastical? (Unreal?) Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Akim Reinhardt

No longer eating meat was similar to no longer believing in God. I can’t pinpoint a moment when it ended, for abstinence did not come upon me suddenly. Rather, what had once been a bedrock of my existence slipped away after years of contemplation. Some time in 1995, I realized it was no longer part of my life. This coincided with me moving to Nebraska, which did not make giving it up any easier. Meat, that is. God was a few years earlier.

But why?

More and more it seemed to me that the differences between dogs and cows and monkeys and horses and pigs and cats and us were not so vast. Mammals were too much like each other for me to feel okay about killing and consuming them for pleasure, as it were, since I didn’t need to eat meat. If it were 18th century America, of course I would. What alternative would I have? But with the 21st century rapidly approaching, meat was a luxury I could forego. And it felt hypocritical to ask someone else, anonymous minimum wage workers on slaughterhouse assembly lines, to slay and gut animals for me if I were now unwilling to do that myself.

I still enjoyed fishing once in a rare while, so I went on eating seafood. Fish still seemed like creatures from another world. But I could look most any mammal in the eye and see a little bit of myself in there.

Or a piece of you. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

In C. Pam Zhang’s new novel Land of Milk and Honey, an agricultural disaster in the Midwest sends clouds of particulates into the atmosphere. Like nuclear winter, the toxic smog suffocates 95% of the plant and animal species on the planet. Famine and societal collapse soon follow~~ and not surprisingly, the super-wealthy start making plans. The fat cat in the novel begins by buying a beautiful mountaintop in Italy where there’s still some sunshine because it’s up that high above the smog. And in this beautiful place, he and his daughter start cultivating animals and precious seeds in underground farms and orchards.

His end game involves luring investors with extravagant multi-course tasting menus, where the finest wines are served alongside truffle risotto and the finest Kobe beef steak, long disappeared from the rest of the world, which is surviving (barely) on a mung bean-derived protein.

“What it amounted to was skies that were gray and kitchens that were gray. You could taste it: gray. No olives, no quails, no grapes of the tart green kind … no saffron, no buffalo, no polished short-grain rice.”

So, what is a young American chef to do?

Her longing for sunshine and pistachios is so great she talks her way into the chef job for the fat cat on his mountaintop. Read more »

by David Winner

São Luís: Far Northeast of Brazil

People crowd around a samba band playing on a crumbling colonial staircase. A man in his early twenties lightly touches my shoulder as I climb upwards, whispering something in Portuguese that I don’t understand. I don’t think he’s trying to sell me anything. I stick out, a white American in a black and brown part of Brazil, but no one has been approaching me.

Smiling vaguely at him, I keep going, sipping vacantly from the huge caipirinha that I’d purchased from a street vender earlier in the evening.

Once I reach the top of the stairs, free from the crush of the crowd, I stand listening to the music, inelegantly bumping my hips in some approximation of dancing.

Ten years ago on another riotous Saturday night, I’d visited São Luís before. And found its denizens drinking, dancing, singing all over the Centro Histórico like in some MGM musical. But a fundamental change has occurred. Before, everyone had been evidently heterosexual, no one announcing their queerness in a way that a bystander could detect. But now, below the staircase and the sambistas, throughout the streets, are women coupled with women, men coupled with men, trans men, trans women, and drag queens like I’d landed in a pride parade, a queer explosion only months past Lula’s victory over the virulently homophobic Bolsonaro.

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again.

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again.

I smile, perhaps I say, “sim,” the universal yes of miscomprehension.

But then he speaks to me in a language that I’ve barely heard in São Luís, English.

In recent years, I’ve taken to wearing odd polo shirts that I’ve purchased on my travels, and the young man is sweetly informing me that the one I have on now is “inside out,” that very particular idiom streaming seamlessly from his mouth. Read more »

by Anton Cebalo

In the past decade, the writer Simone Weil has grown in popularity and continues to provoke conversation some 80 years after her death. She was a writer mainly preoccupied with what she called “the needs of the soul.” One of these needs, almost prophetic in its relevance today, is the capacity for attention toward the world which she likened to prayer. Another is the need to be rooted in a community and place, discussed at length in her last book On the Need for Roots written in 1943.

In the past decade, the writer Simone Weil has grown in popularity and continues to provoke conversation some 80 years after her death. She was a writer mainly preoccupied with what she called “the needs of the soul.” One of these needs, almost prophetic in its relevance today, is the capacity for attention toward the world which she likened to prayer. Another is the need to be rooted in a community and place, discussed at length in her last book On the Need for Roots written in 1943.

The question of “rootedness” was a pressing problem, particularly for the first half of the 20th century. In the preface to The Origins of Totalitarianism, philosopher Hannah Arendt noted that the two world wars had produced “homelessness on an unprecedented scale, rootlessness to an unprecedented depth.” As empires and homelands collapsed after WWI, so many were uprooted from the only worlds they had known. And their newfound superfluous condition led many of them toward “fictitious homes” in the postwar years to disastrous results. Indeed, abstract loneliness had become “an everyday experience of the ever-growing masses of our century,” wrote Arendt, which had rendered them vulnerable to totalitarianism. Uprootedness, it seemed, was partly to blame for Europe’s destruction.

Writing earlier than Arendt in 1943, Weil arrived at a similar conclusion in asserting that “rootedness” was a fundamental need of the soul. In On the Need for Roots, she begins her re-rooting of humanity by outlining a few vital ingredients that are required for healthy nourishment. Yet, the key to her idea of rootedness lies in it establishing linkages to the past and future, forming an assemblage of parts that together provide one with necessary meaning. Such relational thinking often appears in Weil’s writing, as does the Greek word “metaxy” which means an “intermediary” or an “in-between place.” Of course, roots can so often be distorted, manipulated for nefarious ends, and imagined as myth. But given that we are intrinsically social beings, the need for roots as a fundamental fact of life remains sacrosanct. Read more »

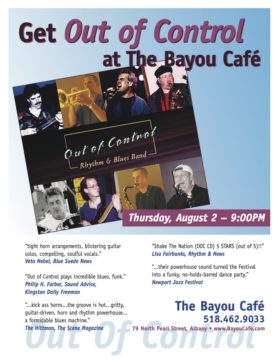

The road was generally somewhere in the Capital District of upstate New York. Think of it as a group of small cities and towns and centered on Albany, the state capital, Troy, where I lived at the time, and Schenectady, incidentally, where my grandfather had his first job in the United States, and where the band rehearsed in the basement of a photography studio in a somewhat sketchy part of town. The studio was owned by Rick Siciliano, lead vocalist and drummer for The Out of Control Rhythm and Blues Band. I played with the band from about 1985 or 86 to 1990 or so.

Not Exactly the Birth of the Blues

I am told that Siciliano started the band in the early 1980s as a means to attract women; I believe Duke Ellington was thinking the same thing when he decided to play piano. Rick got some of his buddies together to form a band. I hear he was better at attracting ladies than getting gigs. Somehow, though, he managed to gather reasonably good musicians. Chris Cernik joined on keyboards and served as den leader; he brought in his high school friend, John Eof on guitar. Then along came “Bad” Bob Maslyn on bass, Ken Drumm on alto and baritone sax to replace Rick’s buddy, Jimmy, and Rick Rourke on alto and tenor sax. There were others in and out of the band, Giles, some trumpeter whose name’s been forgotten, and then John Hines, who’d studied jazz trumpet at Berklee – that’s BerKLEE, the private music school in Boston, not BerKELEY, the flagship campus of the University of California.

They developed a repertoire organized around Blues Brothers tunes and Rick Siciliano’s taste in pop. They even had a couple of originals, “Lady DJ” (for Rick’s lust object du jour) and “Baby Tell the Truth.” Now we’re getting serious. Before you know it, Out of Control was getting gigs, but other bands were after John Hines. They put an ad in the local entertainment weekly, Metroland, looking for a substitute trumpet player.

I saw the ad, needed money, another tried and true motive for playing music. I called Ken, who acted as business manager, and set up an audition. I forget just how the audition process went, but it’s not like there were 30 trumpeters lined up to get the gig. Fact is, the time when trumpet was king was long gone by then so there weren’t many trumpeters, period. I forget just how I learned the tunes, but there were no charts. Perhaps Chris or Ken got me a set of rehearsal tapes. Whatever. I just listened and learned by ear, like all real musicians play, except for classical cats and other advanced miscreants. I soon became the one-and-only full-time trumpeter for the band. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

Suppose you have loved yo-yos since you were a child. You’ve spent countless hours hanging out with other yo-yoers, learning tricks, and reading up on the history of yo-yos (which date back to at least 500 BCE (see above detail of Greek terracotta: “Boy with Yo-Yo circa 440 BCE”)).

You have also spent the last ten years fundraising, planning, and participating in the building of the greatest yo-yo museum/yo-yo venue the world has ever seen. Now, tonight is the grand opening. You will be on stage yo-yoing with the greatest yo-yoers in the world. This is what you have always wanted. On your way to the venue, however, you suddenly realize that you don’t care about yo-yos anymore. In fact, if anything, they have begun to annoy you. You feel certain that you never want to yo-yo, or watch people yo-yo, or even see another yo-yo for the rest of your life.

But here you are in front of the venue. People are gesturing for you to come in. It feels like the person who would have wanted to go in there is a different person than the person that you are now. They are not you. You are not them. Yet, they have sacrificed so much to get here. Time, money, relationships – all gone now – in service of a love of yo-yos and a desire to be on-stage celebrating the opening of the world’s greatest yo-yo museum. A desire you don’t feel anymore.

Should you go in anyway? Do you owe it to your former self, who sacrificed so much to get here, to follow through and go in and yo and yo and yo? Can we even make sense of the idea that one could owe one’s own past self something? Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

In debates about hedonism and the role of pleasure in life, we too often associate pleasure with passive consumption and then complain that a life devoted to passive consumption is unproductive and unserious. But this ignores the fact that the most enduring and life-sustaining pleasures are those in which we find joy in our activities and the exercise of skills and capacities. Most people find the skillful exercise of an ability to be intensely rewarding. Athletes train, musicians practice, and scholars study not only because such activities lead to beneficial outcomes but because the activity itself is satisfying.

In debates about hedonism and the role of pleasure in life, we too often associate pleasure with passive consumption and then complain that a life devoted to passive consumption is unproductive and unserious. But this ignores the fact that the most enduring and life-sustaining pleasures are those in which we find joy in our activities and the exercise of skills and capacities. Most people find the skillful exercise of an ability to be intensely rewarding. Athletes train, musicians practice, and scholars study not only because such activities lead to beneficial outcomes but because the activity itself is satisfying.

The idea that there is a distinctive and uniquely rewarding form of pleasure generated by skillful activity is not a new idea. Aristotle argued that pleasure is the product of unimpeded activity. Since skills diminish impediments to our activity it follows that we take pleasure in skillful activity. More recently, in a research project that has now spanned several decades, the Hungarian/American psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi has understood the pleasure we take in skillful activity in terms of the concept of “flow,” a state of intense immersion in and focus on a task which is intrinsically rewarding.

The pleasure we experience from skillful activity is most often associated with a performance. It is less often associated with skillful perception. However, it isn’t obvious why the exercise of perceptual skills is not similarly rewarding. If so, that has implications for how we understand the nature of aesthetic experience. When we experience pleasure from viewing a painting, are the properties of the painting generating pleasure or are we taking pleasure in our own skill at apprehending those properties? If it is the latter, the capacity of a work of art to engage the skills of the viewer may be an element in evaluating a work. One enduring question in aesthetics is why we enjoy works that are grotesque, painful to experience, or just plain difficult to understand. If part of aesthetic pleasure is the satisfaction we experience in deploying perceptual skills, that question can be answered by the way in which the work engages perceptual or interpretive skills. Read more »

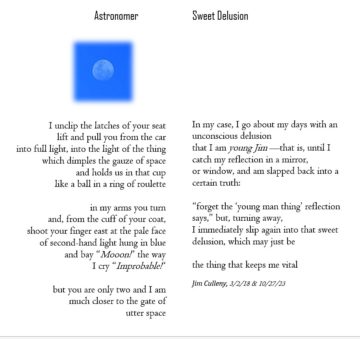

—Two poems separated by 5 years have come together

by Steve Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

French philosopher and sociologist Auguste Comte argued that there ought to be an atheist’s religion, the Religion of Man, with holidays, rituals, symbols, saints, and social gatherings for those who maintain a scientific worldview without belief in an all-being. If such a religion existed, 2023 would be a celebratory year: the centenary of its version of the Council of Nicea, the conference at Erlangen.

The First Council of Nicea, in 325 C.E., brought together bishops from across the Christian world. At the time, there was no single institutional structure and no coherent theology within Christianity. Bishops and theologians held a wide range of positions and endorsed quite different practices, which resulted in a splintering within the Christian community. One question about which there was disagreement: is Jesus God or the son of God? If Jesus isn’t God, then aren’t Christians violating the first commandment not to put other gods before God? If Jesus is God, then how can one be the son of the other? The ensuing debate led to the doctrine of the Trinity coming out of Nicea.

The First Council of Nicea was instigated by the Emperor Constantine, who was understandably fond of strong institutions wielding power. He brought the various players together to hash out their differences and create a unified Church, which then became the dominant power not only in religious life, but in geopolitical matters as well.

A similar impulse guided German advocates of what they termed “the scientific philosophy” in the early decades of the 20th century. Chief among them was philosopher Hans Reichenbach. Read more »

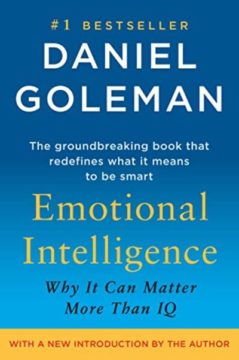

Sughra Raza. Hope.

Digital photograph, July 2020.

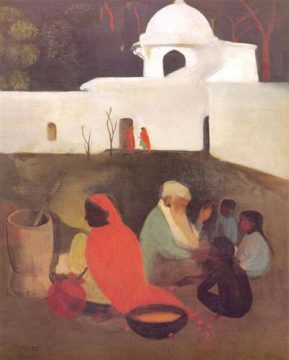

by Claire Chambers

I’m excited about the imminent Halloween publication date of Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia, a book I edited with Siobhan Lambert-Hurley and Tarana Husain Khan. The new book is a partner volume to Desi Delicacies which I edited and wrote about for this blog in 2021.

I’m excited about the imminent Halloween publication date of Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia, a book I edited with Siobhan Lambert-Hurley and Tarana Husain Khan. The new book is a partner volume to Desi Delicacies which I edited and wrote about for this blog in 2021.

One of the most nourishing things about venturing into cookbooks, food writing, and editing heritage recipes has been getting to know a whole new world of South Asian literature. As part of this, I was delighted to be sent Nilosree Biswas’s sumptuous book Calcutta on Your Plate, with its beautiful food photography by Irfan Nabi. Desi Delicacies had included two chapters, one a short story and the other an essay, by Bangladeshi writers. Now Forgotten Foods contains an essay entitled ‘Islam on the Table in [West] Bengal’, in which Jayanta Sengupta especially zeroes in on the Calcutta mutton biryani, complete with its distinctive inclusion of potatoes. However, I didn’t know too much about Bengali cuisine beyond what I had learnt from these pieces, as well as being familiar with British-Bangladeshi curry houses and the eastern South Asian region’s reputation for a sweet tooth. Read more »

South Asian literature. As part of this, I was delighted to be sent Nilosree Biswas’s sumptuous book Calcutta on Your Plate, with its beautiful food photography by Irfan Nabi. Desi Delicacies had included two chapters, one a short story and the other an essay, by Bangladeshi writers. Now Forgotten Foods contains an essay entitled ‘Islam on the Table in [West] Bengal’, in which Jayanta Sengupta especially zeroes in on the Calcutta mutton biryani, complete with its distinctive inclusion of potatoes. However, I didn’t know too much about Bengali cuisine beyond what I had learnt from these pieces, as well as being familiar with British-Bangladeshi curry houses and the eastern South Asian region’s reputation for a sweet tooth. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Jerry Cayford

We think we live in a democracy, though an imperfect one. Every election, our frustrations bubble up in a list of proposed reforms to make our democracy a little more perfect. Usually, changing the Electoral College heads the list, followed by gerrymandering and a motley of campaign finance, voter suppression, vote count integrity, the dominance of swing states, etc. My own frustration is the very banality of this list, its low-energy appearance of arcane, minor, and futile wishes, like dispirited longshot candidates carpooling to Iowa barbecues. Enormous differences among these reforms are masked by the generic label, “electoral reform.”

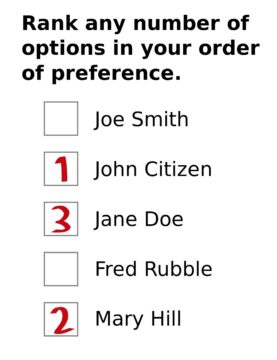

One change—Instant Runoff Voting—should stand alone, for it’s far more important than the others, or even than all of them put together. Democracy is supposed to keep government and voter interests aligned, with elections correcting the government’s course; without runoffs, though, that alignment is elusory because no electoral mechanism really tethers the government to the public interest. Where other flaws in our electoral process have in-built, practical limits on the damage they can do, elections that lack runoffs have no limit on the divergence they allow between leaders and citizens. Which may explain a lot about where we are today.

Many years ago, during the Cold War, I worked for a military policy research company. I had an epiphany there: foreign policy was heavily influenced by the fact that two-player, zero-sum games are easy to analyze. If everything that’s good for the Soviet Union is equally bad for the United States, and vice versa, and no other players matter, it’s easy to settle on a logical action in any situation. Today’s polarized, cutthroat domestic politics is eerily reminiscent of those Cold War foreign policy days. First-past-the-post elections—the kind we mostly have in the U.S., where whoever gets the most votes wins, with or without a majority—produce two parties with perfectly opposed interests and easy “for us or against us” answers. Everyone is familiar with the electoral logic that drives this result: the logic of “spoilers.” The further consequences of spoiler logic, though, are much less familiar. Read more »