by Tim Sommers

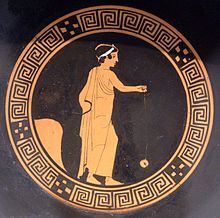

Suppose you have loved yo-yos since you were a child. You’ve spent countless hours hanging out with other yo-yoers, learning tricks, and reading up on the history of yo-yos (which date back to at least 500 BCE (see above detail of Greek terracotta: “Boy with Yo-Yo circa 440 BCE”)).

You have also spent the last ten years fundraising, planning, and participating in the building of the greatest yo-yo museum/yo-yo venue the world has ever seen. Now, tonight is the grand opening. You will be on stage yo-yoing with the greatest yo-yoers in the world. This is what you have always wanted. On your way to the venue, however, you suddenly realize that you don’t care about yo-yos anymore. In fact, if anything, they have begun to annoy you. You feel certain that you never want to yo-yo, or watch people yo-yo, or even see another yo-yo for the rest of your life.

But here you are in front of the venue. People are gesturing for you to come in. It feels like the person who would have wanted to go in there is a different person than the person that you are now. They are not you. You are not them. Yet, they have sacrificed so much to get here. Time, money, relationships – all gone now – in service of a love of yo-yos and a desire to be on-stage celebrating the opening of the world’s greatest yo-yo museum. A desire you don’t feel anymore.

Should you go in anyway? Do you owe it to your former self, who sacrificed so much to get here, to follow through and go in and yo and yo and yo? Can we even make sense of the idea that one could owe one’s own past self something?

If you hold the mistaken belief that there is something fundamentally unserious about yo-yos, substitute your preferred more serious activity here – paleontology, poetry-slams, magic, photo-realistic painting, baseball, philosophy or whatever. The question, as philosopher Ben Bradley puts it is, “If you desired something in the past but you don’t desire it anymore, do you have any prudential reason to bring it about?”

Some philosophers – Bradley focuses on Richard Pettigrew and Dale Dorsey – argue that you do. Dorsey’s view is that “[in a case where my future self ignores my current projects] my future self has failed me—failed to do something that my future self had reason to do given the effort I’ve put in.” According to Dorsey, Bradley says, “I now want my future self to carry out my current plans; so, it would be unfair of me to deny my past self the same courtesy. Expecting my future self to give some weight to what I now want, while denying my past self that courtesy, would be, in a way, inconsistent or ‘unsavory.’”

In other words, we might be tempted to think about prudence (using reason to guide our actions) “as involving some sort of cooperation between one’s past, present, and future selves. When I make decisions, I should think of my past and future selves as other people. Just as I must take other people’s welfare into account in order to act morally, I must take my other temporal selves into account in order to act prudently.”

In his fascinating new paper, “The Sacrificer’s Dilemma,” Bradley offers a unique argument against the view that we should “think of prudence as involving a negotiation or compromise between distinct temporal selves, each of which makes claims of justice on the other selves.” It’s this argument I want to focus on.

But first, there’s a well-known counterexample to the idea that the desires of our past selves might matter at all to us: Brandt’s Roller-Coaster. Suppose as a child you fervently wished to ride a roller-coaster on your fiftieth birthday. Now, it’s your fiftieth birthday, your joints ache and you have a bad back. You are not interested in riding a jerky coaster. Most people have the intuition that having wished to do so as a child, given that you don’t want to now, is no reason at all to ride the coaster. Pettigrew and Dorsey respond that, while not every past desire – this one, for example – creates an obligation, some do. But Bradley uses time travel as a heuristic to get at how this view goes wrong.

Suppose the most painful sacrifice you made for yo-yos was persisting in your work on the yo-yo museum despite your partner, first, threatening, and then actually, leaving you. You told yourself at the time that the sacrifice would be worth it – one day you would be a part of yo-yo history. Now that you don’t care about yo-yos you feel bad about the sacrifices made by your former self, but you still don’t want anything to do with yo-yos. Luckily, since you have access to a time machine, you can go back to the past and make sure that either your partner does not leave your past self or that you can compensate your past self in some other way. But wait! If the partner never left, because you prevented it via time travel, then your past self didn’t suffer the suffering that you were motivated to go back to alleviate. “We have a reason to travel back if and only we don’t do it,” Bradley says. But if you do it, you have no reason to have done it. Time travel always ends in paradox. So, is this just another time travel paradox? Maybe not.

Bradley argues that we can get stuck with “some of the same kinds of paradoxes and dilemmas that genuine time travel or backwards causation would generate” in these cases even without the time machine.

One might try to capture the central claim of the ‘you owe your past self’ view with something like Pettigrew’s “Beneficiary Principle: A current self that has justly benefitted from certain sorts of sacrifice made by some of its past selves has an obligation to give a certain amount of weight to the preferences of these past selves.” My former self sacrificed an important relationship to be on the stage and yo-yoing at the grand opening (and more!), I now have some obligation to either follow through or compensate my past self in some way.

For this to make sense in the case where we don’t have a time machine, we must accept something like “The Redeeming the Past Principle (RPP): someone’s welfare at [a time] can be affected by things happening after [that time].” Dorsey explicitly endorses that principle. “If I value now climbing Mount Everest in [the future], and I do it, that I do so makes me better off now.”

So, here’s Bradley’s argument. Even if sacrifices in the past mean your past selves deserve compensation, and there are ways to compensate your past self in some cases (since someone’s welfare can be affected by things that happen later). To the extent that you compensate your past selves (time machine or not), you necessarily also take away any reason to compensate them. RPP allows you to change the past, in a way. But just like changing the past with a time machine, if you do it, you give your present and future self no reason to do it or have done it. If you do it, you have no reason to do it. “This conclusion is unacceptable; it cannot be the case that someone has reason to do something if and only if they do not do it.”

But here’s an objection to that argument. If I am thirsty and I drink a glass of water, I no longer have a reason to drink a glass of water. How is that different from the Bradley case? I had a reason to do something until I did it and now, having done it, I have no reason to do it. Isn’t that a case of someone having a reason to do something if and only if they haven’t done it?

In the water case, first, at a specific time that we will call t, I am thirsty; then, at time t+1, I drink water; until finally, at time t+2, I am no longer thirsty. There’s no time at which I have a reason to drink the water only if I don’t drink it. I always have or had a reason to drink at time t. But in the RPP case the moment at which I act to change the past is itself one of the moments in which I have no reason to act if I do.

The kind of thing that I can do to affect the welfare of my past self is to now honor a preference of theirs that I no longer share. That doesn’t look paradoxical. I think Bradley’s argument, again, is that changing the past – even without retrocausality – creates a paradox because it still makes the past different in a way, say drinking water, does not. Once I fulfill my past self’s’ desire, there is a sense in which it was always fulfilled (because it was always in the past). If I can compensate myself in the past, even if just in this quasi-logical way, I am eliminating what would give me a reason to change it.

Here’s where Bradley’s titular “sacrifice” language helps. My former self sacrificed a relationship to make the yo-yo venue happen, that’s why I owe it to them to fulfill their desire to go inside and yo-yo. But if I fulfill that desire at any point, what my past self did is no longer a sacrifice, and so I have no reason to compensate them for a sacrifice they ended up not making. Bradley says that “the agent has reason at t to bring it about that P if and only if the agent does not at t bring it about that P.” You have a reason, hypothetically, to fulfill your past selves preference in this case, but if you do, you no longer have a reason.

The point is that “Paying back one’s past self is not a good way to think about the reasons we have, if any, to care about our past values,” Bradley says. That seems right.

There’s a lot more there detail-wise. And philosophy is all in the details. But let’s hope we got this part straight. I will let you know when a full version of the paper is available. A few final comments.

(1) Recall the “Beneficiary Principle.” A current self that has justly benefitted from certain sorts of sacrifice made by some of its past selves has an obligation to give a certain amount of weight to the preferences of those past selves. What kind of obligation? Do the preferences of past selves have moral or prudential weight? Any given past self is either you, or it isn’t you. If it isn’t you, you could only have a moral, and not a prudential, obligation. If it is you, then why shouldn’t you always do what you want now, and not what you wanted in the past – but no longer want. Derek Parfit, the most influential precursor to the kind of view Dorsey and Pettigrew take, intentionally blurred the line between morality and prudence – our obligations to our own future and past selves are very much like our obligations to others. Moral obligations. But I wonder what happens to the Dorsey/Pettigrew position if the obligation to past selves are not prudential. If you’ve changed enough to be a new person, it seems to me, you have no prudential obligations to a former selves. If you have a moral obligation, why is stronger than your obligations to anyone? Either way, this is not a good model of prudence.

(2) Finally, under all the abstractions, it seems to me, the view that you can owe it to your past self to do things that you no longer want to do because your past self put so much effort into it, hides some very bad advice about prudence. Saying “my future self has failed me—failed to do something that my future self had reason to do given the effort I’ve put in,” as Dorsey does, seems to embed the fallacy of sunk cost into our very conception of prudence. Wouldn’t be prudent.

(3) Since I wrote (2), Bradley pointed out to me that Dorsey and Pettigrew would likely simply deny that “honoring sunk costs” is a fallacy, as some other recent philosophers also have (e.g., Doody and Kelly). This doesn’t seem promising to me. For example, Doody’s defense of following sunk costs as a rational way to act is “so that a plausible story can be told about you according to which you haven’t suffered.” A joke from my graduate school days seems apropos here. That’s not a counterexample to my argument, that is my argument. But I have gone on too long.

Big thanks to Ben Bradley for sharing his paper hot, and not even quite “off the press” yet, paper “The Sacrificer’s Dilemma” as well as taking the time to peruse a draft of this. Mistakes, confusions, etc. continue to be all mine, of course.