by Jerry Cayford

We think we live in a democracy, though an imperfect one. Every election, our frustrations bubble up in a list of proposed reforms to make our democracy a little more perfect. Usually, changing the Electoral College heads the list, followed by gerrymandering and a motley of campaign finance, voter suppression, vote count integrity, the dominance of swing states, etc. My own frustration is the very banality of this list, its low-energy appearance of arcane, minor, and futile wishes, like dispirited longshot candidates carpooling to Iowa barbecues. Enormous differences among these reforms are masked by the generic label, “electoral reform.”

One change—Instant Runoff Voting—should stand alone, for it’s far more important than the others, or even than all of them put together. Democracy is supposed to keep government and voter interests aligned, with elections correcting the government’s course; without runoffs, though, that alignment is elusory because no electoral mechanism really tethers the government to the public interest. Where other flaws in our electoral process have in-built, practical limits on the damage they can do, elections that lack runoffs have no limit on the divergence they allow between leaders and citizens. Which may explain a lot about where we are today.

Many years ago, during the Cold War, I worked for a military policy research company. I had an epiphany there: foreign policy was heavily influenced by the fact that two-player, zero-sum games are easy to analyze. If everything that’s good for the Soviet Union is equally bad for the United States, and vice versa, and no other players matter, it’s easy to settle on a logical action in any situation. Today’s polarized, cutthroat domestic politics is eerily reminiscent of those Cold War foreign policy days. First-past-the-post elections—the kind we mostly have in the U.S., where whoever gets the most votes wins, with or without a majority—produce two parties with perfectly opposed interests and easy “for us or against us” answers. Everyone is familiar with the electoral logic that drives this result: the logic of “spoilers.” The further consequences of spoiler logic, though, are much less familiar.

The Stranglehold of Two

A spoiler is a candidate who can’t win but can take enough votes to cause one of the two leaders to lose. Knowing this can happen, people who would vote for the spoiler won’t risk wasting their votes, if they care which of the two leaders wins. Voter support for candidates perceived as third or lower is therefore unstable—hard to acquire and easy to lose—while support for the top two is highly stable. This inescapable spoiler logic—choose between the top two if they’re close, because other votes are wasted—creates a reinforcing cycle in which other parties fall behind and never win, and the system settles into equilibrium with two dominant parties.

Despite the spoiler logic, a few first-past-the-post elections will still be spoiled because a percentage of voters will vote third-party even when they care who wins. “Spoiled” here means that, of the two leading candidates, the one preferred by more voters loses to the other. Electoral reforms, in general, are motivated by the fact that imperfect elections can fail to produce the winners whose policies the public prefers. These electoral failures do harm the public interest. What keeps electoral reforms a low priority, though, is the question of magnitude: how big is the problem? After all, only close elections allow, for example, the Electoral College to diverge from the popular vote; and only close elections can be spoiled.

We need some apparatus for measuring harm to the public interest, which can be tricky to analyze, since it is ultimately neither definable nor quantifiable. But we can make crude approximations by relying on the idea that people know their own interests. Let’s assume the following: the public interest is the policies that the public prefers; the purpose of elections is to choose leaders who will implement those policies; and the winner’s margin of victory measures the magnitude of the public’s interest. This schema is fairly intuitive: a close election means the public collectively has a slight preference for the winner’s policies, a landslide means the public strongly prefers them, and the public’s preferences are a good proxy for their interests.

If runoffs only prevent spoilers, they would be curing a minor harm, one that only happens in elections where the public’s preference for one leader over the other is slight (i.e. low magnitude of public interest). But preventing spoilers is only the most superficial benefit of runoffs; they also correct much bigger flaws in our two-party, first-past-the-post electoral system. Let’s look first at the mechanics of Instant Runoff Voting (IRV) and then at the nature and magnitude of the damage it repairs.

Finding Where the People Are

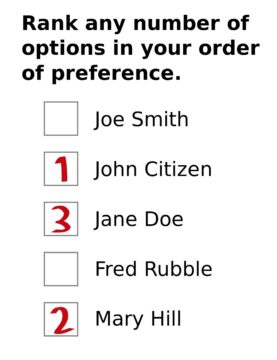

Runoffs solve the problem of spoilers by eliminating losing candidates and then rerunning the vote so that all voters express a choice between the top two. (This is the process Republicans used to winnow seven candidates down to Mike Johnson, now speaker of the House.) In the past, runoffs were expensive, because the whole election had to be rerun a few weeks later. Instant Runoff Voting records voters’ preferences on the first ballot so that runoffs can be conducted by computer without additional balloting. Voters rank the candidates in order of preference (IRV is also sometimes called “Ranked Choice Voting,” RCV). When votes are counted, the candidate who comes in last is eliminated and that candidate’s ballots are distributed to each ballot’s next highest ranked candidate. The process is repeated until all ballots are distributed between the last two candidates, one of whom will have a majority. So, IRV captures the preferences of all voters.

Aside from preventing spoiled elections, IRV enables voters to vote their real preferences. This points to a larger problem caused by spoiler logic: when people vote contrary to their preferences, for fear of wasting their votes, their real preferences are hidden, and therefore so is the public interest. The damage to the public interest of an electoral failure might be much greater than first appears. To see how, let’s pick a baseline and measure damage from there. Initially, we might think we’re all in this two-party, zero-sum game together, and presumably we want roughly what the two parties offer. So, let’s call the median between the two parties’ candidates “zero,” and ask where the voters’ preferences fall relative to zero, using vote margins (the metric in our crude quantification of impacts on the public interest).

In a successful election, voters preferred the winner, so public interest falls above zero (by a little or a lot). In a spoiled election, voters preferred the loser (of the two leaders): public interest below zero (by the small vote margin of a close election). Now we see the possibility, though, that the majority of voters’ real preference (hidden by spoiler logic) could be for some candidate who comes in a distant third: public interest much less than zero.

I’ve just sketched a possibility, but the late, great Molly Ivins painted a wonderful picture of what that possibility looks like in practice. This is from her scathing denunciation (January, 2006) of the gutless Democrats for acquiescing to Republican hostility toward popular policies:

The majority (65 percent) of the American people want single-payer health care and are willing to pay more taxes to get it. The majority (86 percent) of the American people favor raising the minimum wage. The majority of the American people (60 percent) favor repealing Bush’s tax cuts, or at least those that go only to the rich. The majority (66 percent) wants to reduce the deficit not by cutting domestic spending, but by reducing Pentagon spending or raising taxes. The majority (77 percent) thinks we should do “whatever it takes” to protect the environment. The majority (87 percent) thinks big oil companies are gouging consumers and would support a windfall profits tax. That is the center, you fools. WHO ARE YOU AFRAID OF?

Imagine Ivins’s list as the policies of a third-party candidate (the first two parties aren’t implementing them!), and those poll numbers as the percentage of votes the candidate would receive but for the spoiler logic that will make that candidate lose. Those six policies average 73.5 percent popularity, so it is a landslide winning candidate who is losing and whose policies are not being implemented.

After eighteen years, what stands out about Ivins’s list is that all of these policies are still nationally prominent, all of them are still popular (the polling will have changed), and yet we have made almost no progress on any of them! (Some state and local progress on the minimum wage.) And Ivins is not picking the hard cases but rather the opposite, the issues where it is baffling how the government can fail to do what the people want. It turns out, if the two major parties won’t fight for the public interest, the public has no mechanism to compel them to do so. Instant Runoff Voting is that mechanism.

Leaders Untethered from the People

We are analyzing how far government can diverge from the public interest in a first-past-the-post system. First, there can be spoiled elections: instead of electing the leader that the public prefers, a spoiler causes the other leading candidate to win. Second, the real preferences of the voters could be for policies neither of the leaders offer, but we can only choose one of those two, anyway. Third, our examination of spoiler logic—your vote is wasted if it’s not for one of the two leaders—raises a startling possibility: the public’s main concerns can, in theory, be excluded entirely from the government, if the two parties choose not to compete on them. In that case, of course, we would not be a democracy at all.

Each of those three steps shows a widening gap between what the public wants and what sort of government the electoral system produces for them. Whether or not we’re at the extreme, the two-party system puts us on a sliding scale, and how much of a democracy we are depends on how responsive to the public interest those two parties choose to be.

Eighteen years with no progress on any policy in Molly Ivins’s list should alert us to the forces working against the public interest, forces that threaten our democracy by convincing the two parties not to compete on certain issues. The biggest of those issues is the constraint of corporate power. For the last fifty years, that’s been off the table. The Democratic and Republican parties both decided that taking a soft touch with corporate interests was essential to their own electoral success. So we live in a new Gilded Age, with wealth inequality as high as the 1890s or 1920s, middle class income stagnant since the 1970s, union membership at historic lows, corporate monopoly at historic highs, and the power and impunity of those monopolies hollowing out our democracy. (The best introduction I know of to this history is Thomas Frank’s Listen Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People?)

Monopoly is a good lens through which to view our first-past-the-post electoral system, because spoiler logic gives the two parties monopoly control of government policy. As monopolists, they have little incentive to pick fights with other powerful monopolies, and little vulnerability to coercion to do so. It is not surprising, then, that the two parties have chosen to exclude the control of corporate power from the political process, or that the result over decades has been extreme concentration in industries across our economy. It might have continued that way (it still might), had not the Great Recession brought “too big to fail” sharply into public view. Pressure began building, and though the parties may be insulated from public pressure, they are not totally impervious. After decades of being brushed aside by both parties, the anti-monopoly movement is finally getting some traction the last few years, including several high appointments in the Biden Administration.

It would be premature to conclude that renewed attention to monopolies means the public interest has won out, and corporate power is finally being reined in. As the Ivins list of enduringly unsuccessful policies proves, attention does not even imply progress, let alone full repair. Matt Stoller, whose newsletter BIG chronicles monopolies throughout our economy, as well as the anti-monopoly movement’s efforts against them, gives the very topical example of our government’s timid efforts to get monopoly arms manufacturers to increase ammunition production to supply Ukraine and now, potentially, Israel: “But if you actually look at the guts of the bureaucracy, nothing is happening, because doing something about our industrial base means thwarting Wall Street, and that’s generally not something that’s considered on the table among normie policymakers.” We are still very far from making the two parties and the government responsive to the public interest.

Perhaps the renewed attention the anti-monopoly movement is bringing to the damage of monopoly and the benefits of competition will also illuminate the benefits that competition would bring to our elections through IRV. Runoffs remove the two parties’ immunity from challengers who are closer to the public’s preferences. Everything else flows from that: better information about what the voters’ preferences really are, office holders more responsive to those preferences, viable third-party candidates, the end of the zero-sum mentality between the two parties, and less of the extremism, incivility, and polarization that comes with it. In short, government tethered to the public interest, as it’s supposed to be in a democracy.

The Good Fight

Like all monopolists, the two dominant political parties do not like competition. Both the Democratic and the Republican parties fight vigorously to stop IRV wherever reformers try to implement it. Despite the resistance of the parties, though, the benefits of IRV are so great that gradually it is gaining acceptance. Maine and Alaska recently adopted it, the first times it’s been used statewide, and dozens of cities have already implemented it. So, the prognosis is good. Still, I will end with a concern.

Ten years ago, when I was a member of the Board of Directors of Common Cause Maryland, I gave a presentation to the board on IRV. I looked into and presented the work of FairVote, the main national organization lobbying for IRV, which they now call RCV. (I prefer the functional label “Instant Runoff Voting” to the descriptive label “Ranked Choice Voting” because drawing people’s attention to the purpose (function) of the procedure is important, and its purpose is to have elections include runoffs. The neutrally descriptive RCV label forebodes a disturbing insensitivity to what is most important here. As I have argued above, runoffs are what bring benefits orders of magnitude greater than other electoral features or reforms.)

At that time, FairVote’s focus was on IRV/RCV. But now they are pushing a bill in Congress that, besides mandating IRV, would also create larger, multi-member districts (to address gerrymandering, as well). My father told me of a referendum on IRV plus multi-member ridings (districts) in British Columbia, where he lives, but said he hadn’t really understood the redistricting part of it. The Wikipedia entry for the 2018 BC referendum is pretty eye-opening: the referendum was hilariously complex and confusing! It pits the status quo against proportional representation (PR), then offers a choice of three PR subtypes, with different subtypes for urban and rural districts, and with the runoff feature implicit in some types and explicit in others. Another Vancouver friend believes the complexity was deliberate sabotage. A simpler referendum almost passed in 2005, but the 2018 one lost badly.

I don’t know why FairVote is pushing a complex bill that combines runoff voting with multi-member districts, but it is a bad idea for many reasons. First, it is wrong in principle to combine disparate issues as a package: it is coercive to demand that people take all or nothing of a package instead of allowing separate votes on the parts. If multi-member districts have sufficient benefits, they should be able to pass in a stand-alone bill.

Second, it is foolish in practice because this bill will not pass. Multi-member districts are a very radical change to our electoral system—completely unfamiliar to the public, and somewhat antithetical to our cultural idea of “my representative”—with both pros and cons too complicated to pass in the foreseeable future. IRV, for all its profound importance, is not radical but is a simple, familiar, and unalloyed improvement.

Third, most of the benefits of multi-member districts will be realized by IRV over time. With reduced extremism and polarization, and the two parties forced to move closer to the public’s preferences, the practical impacts of gerrymandering will shrink. For the impacts that remain, there are other, less radical and less controversial methods to address gerrymandering. (My preference is redistricting by mathematical algorithm, which has been studied by the MGGG Redistricting Lab, who has done modeling for FairVote.)

Linking runoffs and multi-member districts can only have the effect of acting as a poison pill to drag down the much more politically feasible and much more important Instant Runoff Voting. It is a classic case of making the perfect the enemy of the good. (And if multi-member districting is indeed part of a perfect electoral system, it should still be debated on its own.)

There is lots of talk these days about “threats to democracy” from many and complicated causes. But sometimes, underneath complexity there are simple and necessary solutions. Way down beneath all those complicated threats is one vital electoral flaw: our lack of runoffs, which are necessary to tie government policy to the public interest. Too much money, too much power, too many opportunities for mischief flow to the two parties from staying untethered. And we the people lose. Instant Runoff Voting will do more than anything else—maybe more than everything else—to make our democracy work.