by Rafaël Newman

By a quirk of the calendars, Passover, the annual commemoration of the flight from bondage, is precisely coterminous this year with Academic Travel. This latter, a twice-yearly feature of the university in Switzerland at which I am guest teaching this semester, is that institution’s “signature program”: a week-and-a-half course, typically offered in a location outside Switzerland, focusing on a topic arising from that site. A chance for students to read a city, as it were, like a text.

This year, for obvious reasons, Academic Travel has been canceled – or rather, radically curtailed, with students in the university’s home city of Lugano, in the canton of Ticino, required to produce negative virus tests before traveling merely to other parts of Switzerland, all reachable by train and bus, instead of, as in years past, flying to more appealingly distant locations, such as Poland, Greece, Turkey, and points further afield. For now even relatively nearby destinations, such as Italy or France, have been ruled out by the authorities, shrinking the offerings for the spring semester’s Academic Travel to the familiar hotspots of the Swiss grand tour – Lucerne, Zermatt, Geneva – which are then to serve as makeshift staging grounds for courses on topics in environmental science, history, economics, and the like.

And thus the Jewish festival of Passover, a holiday explicitly celebrating escape from plague, freedom of movement, and the crossing of borders, falls during a period in which students, under threat of contagion, are subject to personal restriction, and are confined within the borders of their current national location.

The convergence of a traditional commemoration of ancient release from bondage with a frustrated travel project in the present is especially poignant for me, perhaps yet more so for my students, since the course I am teaching them in regular session, on “Jewish Writing in German”, involves among other things the reading of three texts that treat themes of migration from a variety of perspectives, and in each of which a Passover scene figures centrally.

In Joseph Roth’s Hiob (1930), modeled on the Book of Job, the tale’s dénouement occurs at a Seder, or ritual Passover table, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, at which a long-lost son reappears unexpectedly, indeed miraculously, from Russia, in a mixture of Odyssean and crypto-Christian motifs. Nearly a century later, Thomas Meyer, in his Wolkenbruchs wunderliche Reise in die Arme einer Schickse (2012, filmed as The Awakening of Motti Wolkenbruch), a comic bildungsroman set in Zurich’s Orthodox community, stages the first stirrings of the protagonist’s emancipation from his tyrannical mother, and his foray into the not always welcoming gentile world around him, amid bitter herbs and memories of the Pharaoh. And in Überbitten (2014), her German-language adaptation and expansion of two earlier, American memoirs – one of them entitled Exodus – Deborah Feldman uses the account of the Hebrews’ escape from Egyptian servitude as a figure for her own release from the stifling religious fundamentalism of her upbringing in Brooklyn, into the freedom of a secular life in secular, multicultural, post-unification Berlin.

That Passover should lend itself so easily as a narrative fulcrum is understandable, since not only does the holiday commemorate a historico-mythical event recounted in the Jewish bible, and thus more or less automatically provide an attractive basis for allegory; it also features a special, purpose-created literary text as one of its indispensable elements. The Haggadah is a retelling of the Exodus story, tailored for the festive occasion with speaking parts for the various guests, culinary stage directions, songs, and rabbinical commentary. There are multiple versions of the book – for it is typically the length of a novella – catering to every possible Jewish type, from the insular zealot to the secular rebel. Its account of slavery and heroic escape under inspired leadership, with the bittersweet savor of revenge on one’s oppressors, can be read, depending on the interpreter’s inclination, as the factual history of a vindicated tribe, the mystical adumbration of any number of spiritual awakenings, or the hieratic prefiguring of a worldly struggle. Thus the early Zionists used archeological methods to track the ancient Hebrews’ itinerary, while the most celebrated of the African American spirituals, “Go Down Moses”, projects the plight of the enslaved in the Antebellum South onto ancient Egypt. Characteristically, Quentin Tarantino focuses on the revenge aspect of the narrative in Inglourious Basterds, his counterfactual fantasy of escape from Der Führer, the 20th century’s answer to Pharaoh; while especially progressive, reform Jewish Seders may add non-traditional elements to the banquet’s array of symbolic foods to gloss contemporary identity-political struggles as versions of Exodus. (I have also heard tell of a Yiddish-language group on the West Coast of Canada that decided to hold its own secular, socialist Passover ceremony, and nominated one of its number to create a new Haggadah for the occasion, in mame-loshn, without mention of God – but ultimately found that it was impossible to excise the metaphysical element from the history of the Hebrews, for whom monotheism was a central and foundational, indeed political institution.) The Passover ritual is so readily available to narrative because at its core is a story that is itself eminently “accessible” to a wide range of retailers; most recently, in my own immediate circle, my younger daughter wrote her senior thesis, on Jewish identity in a secular age, as an imaginary Passover dinner, with a series of internal monologues revealing the attendees’ views on their relationship with Judaism couched in the discourse of the Haggadah.

In the wake of the Shoah, it might be expected that the Exodus narrative would come to figure in revised Haggadahs as an account of those who suffered, and of the few who survived, the genocide, who made it out of Europe, whether their destination was Palestine, the Americas, Asia, or any other place willing to accept Jewish refugees. And indeed, among the refinements made to the text in recent times is the addition of a Fifth Child to the roster of four canonical characters, each of them given a particularly nuanced question to ask of the person leading the Seder: the Wise Child, for instance, asks respectfully, “What are the testimonies, statutes, and judgments we learn through the Passover story?”, while the Wicked Child sneers, “What does this service mean to you?” The newly added Fifth Child, said to represent the victims of Nazi terror, asks merely, “Why?”, gesturing at the bleak theodicy that is the inevitable result of a sustained theological confrontation with the Shoah. How is belief in a just God to be sustained after Auschwitz? – an echo of the Jobian dilemma restaged by Roth in 1930, as the Nazis were gearing up. How is reconciliation possible with a Europe in which other nations happily followed the lead of the German genocidalists? – Meyer’s gesture, in his Jewish protagonist’s uneasy and ultimately unsuccessful attempt at assimilation.

***

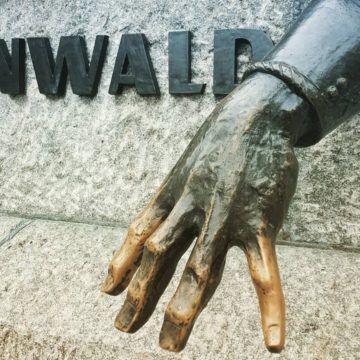

The Academic Travel course on which I have most often served as an assistant lecturer, as it happens, has been held in Berlin, where participants have studied commemoration of the Shoah and traced the route of the Wall. (The young people who had enrolled in this year’s study trip to the stations of industrial genocide will have to make do with a tour of the sites of Zurich’s encounter with Judeophobia, during medieval outbreaks of the Black Death, as well as a viewing of the Swiss city’s four recently installed Stolpersteine, commemorating local deportees.) For the past 15 years or so, I have regularly accompanied my wife, a full professor at the university at which I am guest lecturing, on these trips to Berlin, where she would guide students around the Topography of Terror, in the former Gestapo HQ; to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, near the Brandenburg Gates; and to the nearby site of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, while I would leaven the fare, on evenings off, with a trip to one of the city’s three opera houses.

Our familiarity with the local offerings, both historical and cultural, stems from two separate sojourns in Berlin, the more recent in 1997/1998, when my wife was turning her dissertation, on memorials to the Shoah in Germany and France, into a book, and I was tending to our elder daughter, then just two years old, to whom we had given the middle name of “Berlin” in honor of our affection for the city. (Although when I went to report our temporary residency at the district registrar’s office I was chagrined by the less than enthusiastic response to my recital of our child’s names: “Berlin?!” exclaimed the woman at the wicket. “If that were my name I would kill myself!”) As we counted down to the publisher’s submission deadline and our impending move to take up employment in Zurich, we balanced research and writing with childcare and administrative duties in a city in the process of recreating itself, memorializing its role in two defunct dictatorships with a palette of variously controversial public monuments.

Our first stay in the city, in 1990/1991, in the heady Gründerzeit that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall, was paradoxically less intense, since we were both still graduate students, not yet young parents, and beginning to cast about for dissertation projects. Mornings were spent at the Freie Universität or the Staatsbibliothek, afternoons hunting for the cheapest beer and ham hocks in Charlottenburg, and evenings queuing for discount tickets at the Deutsche Oper, before trekking back uptown to our sublet flat in the now fashionable district of Prenzlauer Berg, in the Kollwitzkiez neighborhood, at the time still a forlorn ensemble of bullet hole-ridden façades and scowling grocers, under a lingering fug of brown coal. Our front windows looked out on a charmingly decrepit water tower, these days a celebrated tourist landmark; from the windows at the back we peered into a deserted courtyard, and the entrance to the Rykestrasse synagogue.

With an eye to our professional future, we had begun to establish contact with people active in what was coming to be known as Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or “coming to terms with the past”, a special branch of German historiography dedicated to the studious processing of the country’s central role in the catastrophes of the 20th century. Among the archivists, academics, and activists remaking the local memory landscape, both concretely and figuratively, was a woman named Irene Runge, a German-Jewish journalist and sociologist born in 1942 during her father’s American exile and, since the founding of the DDR or German Democratic Republic after the war, a citizen of East Germany. Runge, who was revealed after unification and the opening of the East German secret police files to have served as an informant during the regime, was in 1991 embarking on a career as advocate for Jews from the disintegrating Soviet Union; and it was in this capacity that, 30 years ago this month, she invited us to attend a Passover dinner, hosted by the Jüdischer Kulturverein Berlin, or Berlin Jewish Culture Association, in what was then still referred to as East Berlin, to welcome a group of Jewish immigrants recently arrived from the east.

The USSR at the time was in its death throes. Boris Yeltsin had just been elected to the Russian Congress of People’s Deputies; later that spring he would be made chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, and in summer he would become its president. In August of 1991 he would defy the coup against Gorbachev, making a speech from the top of a tank; and by the fall, with power consolidated in his hands, he would dissolve the USSR and create the Commonwealth of Independent States.

So it was a good time to get out of the country, if you could, and ancestrally Jewish citizens of the crumbling USSR were understandably happy to dust off long-buried links to Judaism in order to qualify for expedited passage to Germany, and points beyond. And indeed, my fellow attendees that night in Berlin did not appear particularly well versed in Passover customs. To my North American eyes they were improbably contemporary: suave and polyglot, seemingly more at home in the modern world than I was – one of their number had a mobile telephone, an extremely rare sight at the time, which he was using to speak to an American contact: “Irving, did you get my fax?” These people were not the Singer family, Roth’s shtetl Jews freshly arrived from the Pale, thoroughly steeped in their religion: my dinner companions that evening were at a loss to follow the Haggadah’s instructions, and required my help when called upon to perform such non-dialectical materialist arcana as dipping their fingers into their goblets and spilling drops of wine on the tablecloth, to symbolically curse mythical adversaries.

It was no surprise, really. After all, these Soviet Jews had fled a system built on largely unsupported triumphalist claims; now they were on their way to a life based, they hoped, in fact rather than theory: so what need had they of new magic and superstitions? They were headed to Western Europe, to Israel, to the United States, to a life in the liberal free-market economies they had once been taught to revile, but which had come to seem like their only salvation. Why linger in the ancient chauvinisms of an ethnocentric theocracy? Our quaint attempt at a German-Jewish reconciliation was just another way station on their personal exodus. And although the Passover ritual traditionally ends with the hope that the festival will be celebrated “next year in Jerusalem”, it is of course quite possible to understand that earthly destination as a symbolic stand-in for one’s own particular goal, whether actual or spiritual – even if some of that evening’s company were, literally, headed to “the Promised Land”.

I realized much later, however, that some of those guests must have subsequently chosen to remain in Germany, rather than, like many non-Jewish citizens of the disintegrating DDR were doing at the time, moving on to the New World. Although she was not at our Seder that evening, since she would not arrive with her family for another three years, Marina Weisband, born in 1987 in Ukraine, is among the ex-Soviet Jews who have made their home in Germany; now a practicing psychologist and politically active as a member of the Green party in Münster, this past January Weisband spoke movingly at the German Bundestag on the Memorial Day for the Victims of National Socialism as a member of the new generation of Jews in Germany, following the venerable Charlotte Knobloch, whose keynote address married an unstinting account of her family’s suffering at the hands of the Nazis with denunciation of the new German right wing and expressions of gratitude for the protections of the German state.

In fact, I was first alerted to those remarkable speeches given on January 27 by a participant in my course, a young Jewish man living in Berlin with his parents, who had themselves arrived in the early 1990s from two far-flung Soviet Republics – one of them Birobidzhan, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast on the border with China established by the Soviet leadership in the 1920s as a “homeland” for the USSR’s Jewish citizens. And although I have determined that the dates of their immigration make it unlikely that my student’s parents were at that Passover table with me in the spring of 1991, it is pleasant to imagine that our paths might have crossed in Berlin at some point, during my first residency there, or during the subsequent period. And I am looking forward to reading with that student, later this semester, and with the rest of my class, Deborah Feldman’s memoir of finding a home at last in Berlin, in the Europe that her Hungarian and German-Jewish forebears had had to flee: in the city of Maimon, and Mendelssohn, and Roth. Most of all, I am hopeful that I will be able sometime soon to accompany my wife on another Academic Travel course to Berlin myself – not as early as this next fall, perhaps, but in the spring of 2022? –; once again to read, with an assembled company, in the wonderful, terrible, multiple text of that city.