by Jerry Cayford

We think we live in a democracy, though an imperfect one. Every election, our frustrations bubble up in a list of proposed reforms to make our democracy a little more perfect. Usually, changing the Electoral College heads the list, followed by gerrymandering and a motley of campaign finance, voter suppression, vote count integrity, the dominance of swing states, etc. My own frustration is the very banality of this list, its low-energy appearance of arcane, minor, and futile wishes, like dispirited longshot candidates carpooling to Iowa barbecues. Enormous differences among these reforms are masked by the generic label, “electoral reform.”

One change—Instant Runoff Voting—should stand alone, for it’s far more important than the others, or even than all of them put together. Democracy is supposed to keep government and voter interests aligned, with elections correcting the government’s course; without runoffs, though, that alignment is elusory because no electoral mechanism really tethers the government to the public interest. Where other flaws in our electoral process have in-built, practical limits on the damage they can do, elections that lack runoffs have no limit on the divergence they allow between leaders and citizens. Which may explain a lot about where we are today.

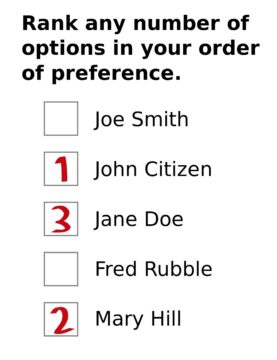

Many years ago, during the Cold War, I worked for a military policy research company. I had an epiphany there: foreign policy was heavily influenced by the fact that two-player, zero-sum games are easy to analyze. If everything that’s good for the Soviet Union is equally bad for the United States, and vice versa, and no other players matter, it’s easy to settle on a logical action in any situation. Today’s polarized, cutthroat domestic politics is eerily reminiscent of those Cold War foreign policy days. First-past-the-post elections—the kind we mostly have in the U.S., where whoever gets the most votes wins, with or without a majority—produce two parties with perfectly opposed interests and easy “for us or against us” answers. Everyone is familiar with the electoral logic that drives this result: the logic of “spoilers.” The further consequences of spoiler logic, though, are much less familiar. Read more »