by Joseph Shieber

Oh, he’s wrong. So are many of the people coming at him.

One of the most-cited passages of Michael Lewis’s new Sam Bankman-Fried book, Going Infinite, is a quote from a blog post from 2012. In that post, a twenty year old Bankman-Fried expresses contempt for the consensus view that Shakespeare is a literary genius.

Bankman-Fried offers two arguments against the consensus view.

The first argument involves an argument on the literary merits: that Shakespeare’s plots rely “on simultaneously one-dimensional and unrealistic characters, illogical plots, and obvious endings.”

The second argument – and the one that raced across the internet after the release of Going Infinite – is a probabilistic one. Given the much smaller population of English speakers in the 16th century, and given the much lower prevalence of education, what are the chances that the best writer in the history of the English language would have been born then? As Bankman-Fried put it:

… the Bayesian priors are pretty damning. About half of the people born since 1600 have been born in the past 100 years, but it gets much worse than that. When Shakespeare wrote almost all of Europeans were busy farming, and very few people attended university; few people were even literate–probably as low as about ten million people. By contrast there are now upwards of a billion literate people in the Western sphere. What are the odds that the greatest writer would have been born in 1564? The Bayesian priors aren’t very favorable.

The problem with this, says the 20 year old Bankman-Fried, is that “We like old plays and old movies and old wines and old instruments and old laws and old people and old records and old music. We like them because they’re old and come with stories but we convince ourselves that there’s more: we convince ourselves that they really were better. … We don’t just respect the old; we think that the old is right and that those who prefer the new to the old are wrong.” Read more »

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021. bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned:

bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned:

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written.

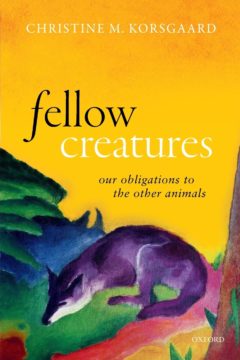

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written. Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club  1.

1. Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012.

Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012. How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s