by Jerry Cayford

The Google advertising technology trial is a very big deal. While we are waiting for the final decision from Judge Leonie Brinkema of the U.S. District Court for Eastern Virginia, I want to present some thoughts on the least resolved of the case’s many issues, the hard parts the judge will be pondering. Actually, one hard part: trust. But I need to tell you a little about the case to make the trust issue clear. I’ll give a brief introduction, but will refer you for more detail to the daily reports I wrote for Big Tech on Trial (BTOT) last September-October.

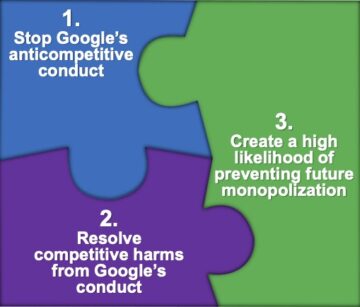

The ad tech trial is the third of three cases in which Google was accused of illegal monopolization, all of which Google lost. The first (brought by Epic Games) was for monopolizing the Android app distribution market. The second was for monopolizing internet search. This one, the third, found Google guilty of a series of dirty tricks to monopolize two advertising technology markets: publisher ad servers, and advertising exchanges. That was in the liability phase, and what we’re waiting for now is the conclusion of the remedy phase of the trial, when we’ll find out what price Google will have to pay for its malfeasance.

I intended to describe for you how a trial on obscure technical issues could possibly be so important, but found I couldn’t. I kept running into unknowably vast questions. This case is about advertising technology, and advertising funds our whole digital world. So it is about who controls the flow of money to businesses. But it is also about the big data and technologies that enable advertising to target you so well, so privacy and autonomy, efficiency and manipulation, democracy and political power are all implicated. Then there’s artificial intelligence; Google’s monopoly on the technologies in this case gives it a big head start in monopolizing AI in coming years. And the rule of law: are the biggest corporations too powerful for law to constrain? This case, perhaps more than any other of our time, will guide the cases against corporate crime lined up behind it. More big issues start crowding in, and I can’t describe it all. So, I’m settling for the most general of summaries, and leaving it at that: the Google ad tech trial lies at the intersection of most of the forces shaping our society’s present and future. That’ll have to do because I’m moving on to the nuts and bolts. Read more »