by Rafaël Newman

Every human generation has its own illusions with regard to civilization; some believe that they are taking part in its upsurge, others that they are witnesses of its extinction. In fact, it always both flames up and smoulders and is extinguished, according to the place and the angle of view. —Ivo Andrić (tr. Lovett F. Edwards)

I was accompanied through the last week of October by a succession of Bosnians: Adnan introduced me to Sarajevo; Emir and Senad took me through Eastern Bosnia; Ajla and Merima led me down the valley of the Neretva River to visit the dervish monastery at Blagaj and the reconstructed bridge at Mostar; and Ahmo, the stoical busman employed by Funky Tours, drove me three 12-hour days in a row through the multiethnic heartland of former Yugoslavia.

It was the time of year when I usually accompany my partner, Caroline Wiedmer, a professor of Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies at Franklin University Switzerland, and a group of students on Academic Travel, the extramural component of a semester-long course with an international theme. (I have written about past travels here, here, and here.) “CLCS 220: Inventing the Past,” a course in memory studies Caroline has offered many times since 2007, has typically focused on French, German, and Polish sites of Holocaust remembrance, an early specialty of hers; this year it was devoted to Sarajevo, as well as to other towns in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to a study of the culture of memory there, nearly thirty years after the Dayton Agreement put an end to the violence and atrocities surrounding the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Our daughter, Hella Wiedmer-Newman, was also along on the trip. Her work as a doctoral student in art history at the University of Basel focuses on art and memorialization in postwar ex-Yugoslavia, and this, together with her growing proficiency in the Bosnian language, made her an obvious choice to lead some of the on-site seminars in Sarajevo.

In fact, however, my late-October series of Bosnian guides was initiated, quite by chance, before I had even touched down at Sarajevo International Airport. On the eve of our departure from Zurich we were invited to dinner at the home of our Ukrainian friends Marichka and Ihor, and, since we were accompanied there by my 95-year-old mother-in-law and her Bolonka, we took a taxi home afterwards. Our driver was a portly, jovial man with a Nabucco-worthy black beard who assured us that all four of us plus the lapdog would fit in his small vehicle. Ferhat (I read his name off the licence posted on his dashboard) was affably chatty during the drive from the Enge district to our home in Unterstrass. His wife was from Macedonia, he informed us, when we explained our family situation, and similarly solicitous of his aging mother; but when I asked whether he too was from the southernmost republic of former Yugoslavia, ready to proffer, as a token of fellowship, my passing acquaintance with that new and controversial nation, Ferhat said that in fact he was Bosnian. And when we told him we would be flying off to Sarajevo the next day, he was overjoyed, and immediately began offering various forms of counsel.

Bosnia, he said, was a safe and peaceful place, largely without violent crime. The one thing to be wary of, according to him, was theft: and he recounted with a certain schadenfreude the experience of a friend in Sarajevo, who had built himself a house so impregnable, with such high, fortress-like walls around its perimeter, that the owner himself was unable to enjoy the view from his balcony. But the punchline was: that very dwelling, despite its elaborate safety features, did eventually fall prey to housebreakers. We laughed at the irony, and I suggested that the friend had brought his misfortune upon himself, by alerting potential thieves by means of his elaborate precautions that the house likely contained something worth stealing. Yes, agreed Ferhat, it might have been wiser to conceal the value of its contents with a humble exterior. Nevertheless, he sighed ruefully, in the end no amount of physical protection or psychological ruse can entirely guard against the malevolence of those willing to besiege you.

Ferhat’s anecdote proved to be the ideal prologue for our visit to Sarajevo. We arrived the next day, on Monday evening, and by 8 a.m. on Tuesday, all 26 of us—three co-instructors and 23 students, mostly sophomores and juniors—had boarded a bus parked on the slope behind our pension in Kasima Efendije Dobrače Street for a tour of pivotal sites of the Siege of Sarajevo. Adnan, the first of our Bosnian guides in country, was a compactly built man in his mid-fifties with an easy smile and a physical ease that belied the war wounds he had sustained during the mid-1990s. His commentary as we drove through downtown Sarajevo, heading southwest along the Miljacka towards the airport, was clear and concise. It was vividly informed by his own eyewitness testimony as a former member of the Bosnian Army, and his fluent English was enlivened by the occasional serendipitous malapropism: the perpetually burning brazier at the junction of Mula Mustafa Bašeskije, Titova, and Ferhadija Streets, dedicated in 1946 to commemorate the liberation of Sarajevo and the birth of the now imploded Yugoslavia, he called the Internal Flame; the Germanic-origin English royal family were the Winsdorfs. Adnan was dryly measured as he recounted horrific facts of the siege, which lasted from April 5, 1992 until February 29, 1996, the longest a capital city has been beleaguered in modern warfare, for a total of 1,425 days—a number that figures prominently on signs posted at Sarajevo city limits on main roads.

Ferhat’s anecdote proved to be the ideal prologue for our visit to Sarajevo. We arrived the next day, on Monday evening, and by 8 a.m. on Tuesday, all 26 of us—three co-instructors and 23 students, mostly sophomores and juniors—had boarded a bus parked on the slope behind our pension in Kasima Efendije Dobrače Street for a tour of pivotal sites of the Siege of Sarajevo. Adnan, the first of our Bosnian guides in country, was a compactly built man in his mid-fifties with an easy smile and a physical ease that belied the war wounds he had sustained during the mid-1990s. His commentary as we drove through downtown Sarajevo, heading southwest along the Miljacka towards the airport, was clear and concise. It was vividly informed by his own eyewitness testimony as a former member of the Bosnian Army, and his fluent English was enlivened by the occasional serendipitous malapropism: the perpetually burning brazier at the junction of Mula Mustafa Bašeskije, Titova, and Ferhadija Streets, dedicated in 1946 to commemorate the liberation of Sarajevo and the birth of the now imploded Yugoslavia, he called the Internal Flame; the Germanic-origin English royal family were the Winsdorfs. Adnan was dryly measured as he recounted horrific facts of the siege, which lasted from April 5, 1992 until February 29, 1996, the longest a capital city has been beleaguered in modern warfare, for a total of 1,425 days—a number that figures prominently on signs posted at Sarajevo city limits on main roads.

Among the sites we visited with Adnan were the Memorial to the Murdered Children of Besieged Sarajevo, an abstract glass sculpture suggesting a parent shielding a child surrounded by shell casings, and the Tunel spasa, or Tunnel of Hope, built by the Bosnian Army under the UN-controlled airport for the provisioning of the besieged city. Along the way our attention was drawn to the infamous Sarajevo Roses, petal-like marks left on Sarajevan pavement by Serb shelling, subsequently highlighted in red paint as if to keep the memory of death and suffering present and alive.

It was not until we reached the city’s Old Jewish Cemetery, however, on the slopes of Mount Trebević, the second largest in Europe after Prague’s, with separate Ashkenazi and Sephardic sections and a monument to the Jews murdered by Croatia’s Ustaše at Jasenovac concentration camp, that the significance of siege in general, and its continuing, baleful reality, was borne in upon us. The cemetery had been on the front line during the war, and had in fact for a time been used by Serb forces as a sniper’s nest; it had now been restored to its previous function, and was being treated with the appropriate piety. This prompted one of the Jewish students in our group to ask Adnan about how Bosniaks, as local Muslims refer to themselves, get along with the country’s remaining Jews, whereupon he responded that, while relations were cordial enough, Bosniaks felt a particular solidarity with Palestinians, especially at the moment. How could they fail to, he asked us, when they know exactly how the Gazans are feeling?

It was not until we reached the city’s Old Jewish Cemetery, however, on the slopes of Mount Trebević, the second largest in Europe after Prague’s, with separate Ashkenazi and Sephardic sections and a monument to the Jews murdered by Croatia’s Ustaše at Jasenovac concentration camp, that the significance of siege in general, and its continuing, baleful reality, was borne in upon us. The cemetery had been on the front line during the war, and had in fact for a time been used by Serb forces as a sniper’s nest; it had now been restored to its previous function, and was being treated with the appropriate piety. This prompted one of the Jewish students in our group to ask Adnan about how Bosniaks, as local Muslims refer to themselves, get along with the country’s remaining Jews, whereupon he responded that, while relations were cordial enough, Bosniaks felt a particular solidarity with Palestinians, especially at the moment. How could they fail to, he asked us, when they know exactly how the Gazans are feeling?

Thereafter, all around me as we returned to the city’s commercial, touristic, and business districts, I began to notice signs, posted more or less prominently, handmade sheets on bus shelters or illuminated billboards, calling for aid to Gaza, for solidarity with Palestine, and for a boycott of Israeli enterprises. And when we arrived, later that week, at the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina for a presentation by the curator, Amar Karapus, we were greeted by graffiti sprayed along the parapet facing Zmaja od Bosne, a busy tram and traffic street: PALESTINIAN LIFES MATTER. The message was unmistakable, its erroneous inflection only serving to further highlight the analogical potential of an idiom borrowed from the American context, referring to the Palestinian, and situated at the site of another, different attempt at ethnic suppression.

A more detailed condemnation of the IDF’s siege and bombardment of Gaza continued inside the museum, as Selma Alispahić, an actress and professor of theater studies at the Sarajevo School for Science and Technology, drew on her own (secular) Muslim background to express solidarity with those suffering in Palestine. She had come to the museum to present to our group the exhibition devoted to her production of a Bosnian-language version of ¡Ay, Carmela!, José Sanchis Sinisterra’s 1987 play about a theater troupe during the Spanish Civil War (filmed by Carlos Saura in 1990). The play, in its original Spanish instantiation already a parable of the political compromises forced on art, acquired an extra layer of allegory when it was performed, beginning in 1999 and for many years thereafter, at the Sarajevo War Theatre, as well as throughout the Western Balkans and in Europe. In Bosnian, without surtitles but with the broad physical comedy of the original, the play acquired the primary force of an antifascist rallying cry; and it has now been preserved at Sarajevo’s Historical Museum as a video loop of the complete performance, surrounded by a diorama of the original props. According to Karapus, this is the first museum exhibition of its kind world-wide.

Alispahić herself, a forthright and vivacious critic of the current global malaise who, like the curator, preserves fond, if not unmixed memories of the theoretical promise of socialist Yugoslavia, said it made more sense to stage an allegory of Bosnia’s struggle, and of the compromises forced on the fight against fascism by political realities, amid a progressive project that failed—the Spanish Republican movement—than among Tito’s triumphant Partisans: since the ultimate failure of that latter antifascist project, in the fateful decade following Tito’s death in 1980, renders it too proximate to serve as allegory, and, with its blood-soaked sequelae in the 1990s, still too contested a history.

But in fact, it was impossible to escape the echoes of the conflict that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia wherever we went in Bosnia and Herzegovina—or rather, in the two entities that it comprises, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska. (There is a third element in the political makeup of the country, Brčko District, whose mix of ethnicities and crucial strategic position led to its being declared a self-governing free city.) My particular contribution to Academic Travels past has been to add a certain “high” culture, if not necessarily comic relief, to an experience otherwise routinely grave and depressing. As a rule, particularly during Caroline’s early years, when she regularly led trips to Berlin, I would take advantage of that city’s three opera houses to accompany students to productions of works by Mozart, Strauss, or Verdi, at the Deutsche Oper, Staatsoper, or Komische Oper, as a counterweight to their visits to the sites of concentration camps and Gestapo torture chambers. I have arranged like excursions in other destinations as well: in Vienna, naturally, as well as in Greece, where in 2018 we attended a production of Janaček’s Jenůfa at the splendid new Stavros Niarchos Hall in Piraeus. (Not especially light-hearted fare, but its distant misery made a change from our topic, the present-day suffering of people who had fled the Syrian conflict for a not always welcoming Greek refuge.)

The same sort of diversion was not available in Bosnia: the Sarajevo National Theatre was not featuring any musical productions in October, and I reasoned that uninterpreted Bosnian-language theater might not offer quite the aesthetic equilibrium I was after. And yet, although we had not visited Auschwitz on this trip, we had driven for three hours to view the killing grounds at Srebrenica, the site of the only genocide Serb officialdom cannot deny; we had looked down from the heights of the Rorovi memorial at Goražde, a town that had withstood its own siege and thus avoided becoming a second Srebrenica; and we had seen Foča, where massacres had been carried out and rape camps maintained. So these students, like their past colleagues in the Bloodlands, had certainly earned a break in tone.

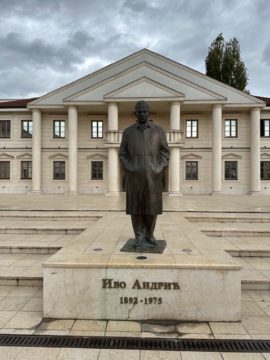

My choice fell on an excursion to Višegrad, in Eastern Bosnia, once the frontier between Serbia and the Ottoman Empire and the setting for a favorite novel, The Bridge on the Drina, by Ivo Andrić. The book, by Yugoslavia’s sole Nobel Prize laureate for literature, in 1961, is an epic—at least in temporal scope, since its action occurs over the course of five centuries: which of course means that it features a changing cast of human characters, Ottoman, Muslim (or “Turk,” in Andrić’s period parlance), Orthodox (or “Serb”), Jewish, and eventually Catholic, or rather Austro-Hungarian. At the book’s center, however, is an inanimate but surprisingly lively figure, the bridge of its title. Built in the late 16th century by the Ottoman Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmet Paşa, partially destroyed in the First and Second World Wars, now rebuilt and still standing to this day, the Most Mehmed-paša Sokolovića (as it is known in Bosnian) is a tribute to its designer, Ottoman court architect Mimar Sinan.

My plan was to lead the students onto the bridge and have them assemble on the sofa, the stone seating built into the bridge’s center, its kappia, across from the tarih, the plaque that rises above the middle of the structure’s eleven graceful arches and recounts, in Ottoman Turkish written with Arabic characters, the history of its construction. It was there that I wanted to give them the story of the bridge as retold by Andrić, and to talk about its significance for the multiethnic history of the region.

And this is just what we did: only a sudden chilly sprinkling of rain obliged me to abbreviate my remarks. I had conveyed to them the Vergilian pathos of Andrić’s account of the bridge’s prehistory, in which the young Christian boy from Sokolovići, a village in the hinterland of Viśegrad, who would one day become the Grand Vizier, was taken from the arms of his mother in the devşirme or “blood tax,” the regular culling of the local peasantry for new conscripts into the Sultan’s corps of janissary soldiers in Istanbul. As Andrić reimagines the scene, when the Sultan’s emissaries and their collection of boys arrive at the as-yet unbridged Drina, followed by a weeping throng of their mothers, the Ottoman train mounts the ferry across the river, leaving the boys’ disconsolate kin on the far bank, never to be reunited with their sons. I had just managed to read the students Andrić’s translation of the tarih, and to note that the bridge, built by the Ottomans in the 16th century and destroyed by the Serbs and Austro-Hungarians in the 19th, stood in the novel for a changing conception of time under various imperial and national hegemonies, when the increasing downpour had us hurrying along to Višegrad’s second attraction.

Andrićgrad occupies the broad spit of land at the confluence of the Drina and Rzav rivers some 300 yards downstream from the bridge. The miniature town-within-a-town—really just the equivalent of two or three city blocks—is an homage to the eponymous author and a celebration of local history and culture, adorned with classically posed, antique-looking statues of such putative Serb heroes as Andrić, born a Croat Catholic, Nikola Tesla, an American of Serb origin, Petar II Petrović-Njegoš, a Montenegrin prince, the Byzantine patriarch shaking hand with a Serb warrior, the whole surrounded by an eclectic, historicizing assortment of architectural styles, complete with cinema, literary center, Andrić Institute, and gift shop.

This peculiarly high-culture, ethno-nationalist Disneyland, tucked away in a remote corner of the Republika Srpska, is the creation of Emir Kusturica, the Muslim-born Bosnian filmmaker who has converted to Orthodoxy and become an apologist for Radovan Karadžić, as Peter Handke has been of Slobodan Milošević. Opened in 2014 to commemorate the assassination of Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip, Andrićgrad also features tributes to other, non-Serb notables, such as Geronimo, Gandhi, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara…and Vladimir Putin. This in a region in which the aggressive Serbian nationalist project, which runs through the entire history of the Balkans during the past century and more, and which has regularly called on Russia for backup, has manifested itself in various guises in each instantiation of the Yugoslav entity, and in which the streets in some small towns are emblazoned with Russian flags and the letter Z, in support of the invasion of Ukraine and as a warning against encroachments from the West or the East. (Provoked and/or justified in part, perhaps, by very real economic ties between the Federation and Turkey: see the photograph at the head of this text.) A perilous confluence of irredentist projects, drawing on mildewed ressentiment, mythologies of blood, and ancient grudges, and dependent on the non-Balkan world’s belief that what unfolded in the breakup of Yugoslavia was in fact the predetermined, robotic enactment of tribal enmities, rather than, as Slavoj Žižek explained at the time, a straightforward expression of power politics, the determination of a ruling elite, which happened to be Serbian Orthodox, to maintain its entrenched dominance over the region. Just as present-day Russia uses specious claims to be the inheritor of Kievan Rus to justify its attack on Ukraine and revanchist campaign of Soviet-era territory.

And suddenly I realized why “1,425”, the number inscribed on signs posted on roads in and out of Sarajevo to inform travelers of the number of days of siege the city had survived, had seemed so uncannily familiar: it had been reminding me of 1453, the year in which the Ottomans had conquered Constantinople and effectively ended the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire. And I recalled the way Ratko Mladić, the general responsible for the genocide at Srebrenica, had referred to the Bosnian Muslims he was planning to murder as “Turks,” in Andrić’s antiquated terminology: as if the siege and fall of Constantinople still called out for revenge by the forces of Christendom; as if the Crusades were still ongoing; as if the Battle of Kosovo Field in 1389, at which Serbian Prince Lazar had met Ottoman forces under the command of Sultan Murad, needed to be refought, the ghostly rematch Milošević had evoked in his infamous 1989 speech and which the Serbs in Northern Kosovo are presently engaged in prosecuting. One siege after another, in a world incapable of learning that vengeance always calls forth more violence: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzogovina beleaguered, Ukraine beleaguered, Kosovo beleaguered, Israel beleaguered, Gaza beleaguered…

That Ivo Andrić should be tacitly enlisted in such a gruesome project seemed like an insult, if at some level understandable. For after all, it is possible to read his work as a critique of Ottoman rule and a reification and justification of the hatred allegedly ingrained in Balkan “blood”. A celebrated, often quoted passage from a 1946 text of his, “A Letter from 1920,” seems to bear this out:

Yes, Bosnia is a country of hatred. That is Bosnia. And by a strange contrast, which in fact isn’t so strange, and could perhaps be easily explained by careful analysis, it can also be said that there are a few countries with such firm belief, elevated strength of character, so much tenderness and loving passion, such depth of feeling, of loyalty and unshakable devotion, or with such a thirst for justice. But in secret depths underneath all this hide burning hatreds, entire hurricanes of tethered and compressed hatreds maturing and awaiting their hour. The relationship between your loves and your hatred is the same as between your high mountains and the invisible geological strata underlying them, a thousand times larger and heavier. And thus you are condemned to live on deep layers of explosive which are lit from time to time by the very sparks of your loves and your fiery and violent emotion.

This manifesto of ethnic strife is underpinned by a lyrical evocation of the differences in the very perception of time that make it impossible for Bosnia’s various tribal affiliations to reconcile with one another:

Whoever lies awake at night in Sarajevo hears the voices of the Sarajevo night. The clock on the Catholic cathedral strikes the hour with weighty confidence: 2 a.m. More than a minute passes (to be exact, seventy-five seconds—I counted) and only then with a rather weaker, but piercing sound does the Orthodox church announce the hour, and chime its own 2 a.m. A moment after it the tower clock on the Bey’s mosque strikes the hour in a hoarse, faraway voice, and that strikes 11, the ghostly Turkish hour, by the strange calculation of distant and alien parts of the world. The Jews have no clock to sound their hour, so God alone knows what time it is for them by the Sephardic reckoning or the Ashkenazi. Thus at night, while everyone is sleeping, division keeps vigil in the counting of the late, small hours, and separates these sleeping people who, awake, rejoice and mourn, feast and fast by four different and antagonistic calendars, and send all their prayers and wishes to one heaven in four different ecclesiastical languages. And this difference, sometimes visible and open, sometimes invisible and hidden, is always similar to hatred, and often completely identical with it.

(Tr. Lenore Grenoble)

And yet, as Misha Glenny has pointed out, Andrić places these words in the mouth of a disillusioned Jewish doctor, a convert, who leaves Bosnia to fight for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War, and to die there. “This is no condemnation of Muslim traditions in Bosnia or anywhere else,” Glenny writes. “It is a condemnation of us all.”

*

On the final day of travel, and the last day of October, I skipped the morning session of Academic Travel—a talk on film and memory at the Sarajevo School of Science and Technology—so I could visit the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the weekly hour during which the Sarajevo Haggadah is available for viewing.

The Sarajevo Haggadah, created likely near Barcelona in the 14th century and taken to the Balkans by Sephardic Jews expelled from Catholic Spain in the late 15th, has survived all manner of violent vicissitudes, most recently the Siege of Sarajevo, and is now preserved by the Bosnian state alongside other relics of Bosnian antiquity. (Its history has been imaginatively reconstructed by Geraldine Brooks in her marvelous 2008 People of the Book.) Gorgeously illuminated and containing full-page illustrations of scenes from the Pentateuch, concluding with the life and death of Moses, the book serves as the traditional guide to the Passover seder service, at which the escape of the Hebrews from bondage under the Pharaoh is annually commemorated.

As I stood before the glass cube in which the Haggadah is displayed, its pages turned to an image of Moses presenting the tablets to his people, I reflected on the possible meaning of such an ancient Jewish prayer book to a secular, Muslim-inflected society with variously revanchist Orthodox and Catholic elements. Could it be that it held out the hope of a similar release from bondage, an escape from a series of latter-day Pharaohs, and the gift of a peaceful life under commonly accepted legislation in a free and united, post-ethnic land? Would the Balkans finally be able to extinguish the internal flame of their division?