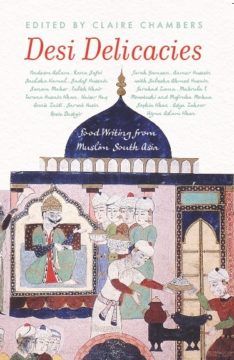

by Claire Chambers

I recently edited an anthology about food from Muslim South Asia. Published by Pan Macmillan in India as Desi Delicacies, the book’s first half is made up of life writing essays, while the second half comprises short stories. To give a taste of the volume, it opens with Bina Shah’s virtuosic Foreword: Appetizer. In it, the author of Before She Sleeps reflects on food’s alchemical ability ‘to prolong life and […] turn base materials into noble ones’. This book, as Shah intimates, abounds with orphans, widows, and divorcees, and memories of the departed make particular repasts taste all the sweeter.

My own love for South Asian Muslim culture, literature, and food was ignited by my year off before university. This is something I touch on in my Introduction: Food in the Time of Corona, which started life as a 3QD blog post. I spent that year in the mid-1990s teaching in Mardan and Peshawar, in the northwestern Pakistani region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. I celebrated my eighteenth birthday there, and it genuinely was a coming of age. The year set me on a course of reading and writing on the topic of South Asian Muslim literature which I have pursued with hardly any interruptions ever since. Along the way, I’ve been lucky enough to get to know some astounding authors, many of whom were gracious enough to contribute to this anthology.

The first piece in Part One: Essays is The Homesick Restaurant, an autobiographical fragment by Nadeem Aslam, one of the best-known Pakistani writers. The piece features a kachnar flower and a long-lost relative, and packs the punch of deggi mirch chilli powder in fewer than a thousand words. Really, it just has to be savoured.

In Qissa Qorma aur Qaliya Ka (All about Qormas and Qaliyas), Rana Safvi takes a panoramic and often nostalgic look at the traditional dastarkhwan (eating area spread with a cloth) and eating etiquette of courtly and historic Lucknow, in contrast with present-day time-saving cookery. The histories and ingredients of the Qormas and Qaliyas of Rana’s title are thoroughly explored, and Lucknavi cuisine’s Central Asian roots are traced. Unsurprisingly, the UK edition of this anthology, to be brought out in spring 2021 by Beacon Books, will bear the title Dastarkhwan.

Next comes Paye, Pressure, and Patience: Life in Pakistani Cooking. This is Sauleha Kamal’s beautiful essay about food from the perspective of a millennial, cosmopolitan, and feminist Pakistani woman. She discusses issues surrounding the division of domestic labour, social media responses to the rise of cooking shows, and her own longing for home cuisine while studying in the diaspora with humour and poignancy. Sauleha also gives the published volume its title, ‘desi delicacies’.

In Alhamdulillah: With Gratitude and Relish, Bangladeshi poet, translator, and academic Kaiser Haq opens with the food of his Bengali childhood and takes us through to the Dhaka restaurant scene of 2020, where ‘anyone coming this way is welcome to join us’. Over the course of these reflections, he pays particular attention to mourning feasts and poor people’s involuntary fasts, seasoning the writing with lines from his own poems.

In The Rise of Pakistan’s ‘Burger’ Generation, Sanam Maher unpicks the half-insulting, half-affectionate nickname, ‘Burger’, which is often bestowed on Westernized Pakistanis. In the  process, Sanam, an intrepid and much-loved journalist and narrative nonfiction author, uncovers the fascinating history of the burger’s arrival in Pakistani restaurants. The centripetal and centrifugal pulls of eating out versus homecooked food will resurface in other chapters from the book too. As well as burger joints, discussion of eating out encompasses tech-savvy delivery services like Foodpanda, and north India’s street food.

process, Sanam, an intrepid and much-loved journalist and narrative nonfiction author, uncovers the fascinating history of the burger’s arrival in Pakistani restaurants. The centripetal and centrifugal pulls of eating out versus homecooked food will resurface in other chapters from the book too. As well as burger joints, discussion of eating out encompasses tech-savvy delivery services like Foodpanda, and north India’s street food.

Indian-Danish novelist Tabish Khair tries to translate the untranslatable word Jootha. This is leftover food that a loved one or servant might (or might not) consume. Khair examines our attitudes towards such waste food. In doing so, he untangles a complex web of food taboos and traditions caught up with class, caste, and intimacy.

Prize-winning Indian author and filmmaker Annie Zaidi writes in Chewing on Secrets about a female tradition of kitty parties, closely-guarded and generously-shared recipes, and, above all, about the love the author’s late grandmother stirred into the sweet dishes she used to make for her young relatives. Try though they might, the family WhatsApp group fail accurately to recreate these desserts.

Young British-Pakistani novelist Sarvat Hasin writes about food, friendship, and falling in love in Stone Soup. In her own words, the essay is about ‘how embarrassingly late I learned to cook anything other than scrambled eggs’. On her journey to domestic goddesshood, she throws a taco party, makes kali dal for comfort, and throws together noodles with a loved one on a snowy day. But above all, Sarvat impresses on readers that ‘cooking is sexy’.

In his funny, foody piece, High on Chai and Samosa, author and Indian Masterchef contestant Sadaf Hussain makes us see those South Asian staples of tea and samosas in a new light. Showing what perfect compatibility these refreshments have with each other, it comes as a surprise that he only became a chai-lover as an adult. In this chapter, he also shows – in his words – ‘how Muslims don’t always dig their nose and hands into Biryani, Kebabs, and Korma’!

Part Two collects together the book’s short stories. In the first of these, ‘Aftertaste’ by Tarana Husain Khan, the protagonist, Sayedani, is someone who bathes the dead and prepares them for funerals. ‘Death comes with an aftertaste of taar roti’ is the story’s unforgettable opening line. Sayedani has the bittersweet experience of eating the sumptuous strands of this crimson curry at the funeral of the wife of an ex-lover. Bowing to family pressure years ago, he had abandoned her to enter into an arranged marriage with this woman, before his own untimely demise.

Part Two collects together the book’s short stories. In the first of these, ‘Aftertaste’ by Tarana Husain Khan, the protagonist, Sayedani, is someone who bathes the dead and prepares them for funerals. ‘Death comes with an aftertaste of taar roti’ is the story’s unforgettable opening line. Sayedani has the bittersweet experience of eating the sumptuous strands of this crimson curry at the funeral of the wife of an ex-lover. Bowing to family pressure years ago, he had abandoned her to enter into an arranged marriage with this woman, before his own untimely demise.

In A Brief History of the Carrot, British-Pakistani novelist Rosie Dastgir’s divorced protagonist Raman struggles to make ‘orange food’ like fish fingers and baked beans for young son Sami in his new position as a single father. The arrival of a pamphlet from an aunt in Pakistan gives him the urge to make the healthy drink black carrot kanji, in the process giving him a restorative zest for life.

In The Hairy Curry, Kashmiri author Asiya Zahoor writes lyrically about a young servant boy from the countryside trying to find his way as a servant in a grand Srinagar home. Readers share his anxiety about mysterious hairs found in the yoghurt curry of lotus roots he has spent the day working to create.

Pakistani-American novelist Uzma Aslam Khan tells the tale of a young daughter, Zulekha, mourning the death of her confectioner father. The gold leaf of her exquisite writing style with which Khan filigrees The Origin of Sweetness – a story of barfi and bereavement – precipitates some unexpected time travel to forgotten food stories of the past.

In The Night of Forgiveness, Farah Yameen conjures up a khichri of women’s frustrations, ambitions, ghosts, madness, and medicine in a joint family setting. These ingredients come together on Shab-e-Barat, the Night of Forgiveness, when halwa is eaten and Muslims stay up praying for absolution from their sins.

With ‘transcreation’ support from his late mother Sabeeha Ahmed Husain, British-Pakistani fiction writer Aamer Hussein casts a wicked eye on the complexities of the service industry in London. Wealthy and ageing, Mrs Meer is let down first by Mr Beg and then a woman named Safia (with whom Beg seems to be having a dalliance) in What’s Cooking? The elderly aristocrat yearns for the perfect biryani to impress her friends, but simply cannot find the help.

London. Wealthy and ageing, Mrs Meer is let down first by Mr Beg and then a woman named Safia (with whom Beg seems to be having a dalliance) in What’s Cooking? The elderly aristocrat yearns for the perfect biryani to impress her friends, but simply cannot find the help.

In But There Are Angels Indian-British novelist Farahad Zama focuses on another divorcee, Faisal, who like Rosie Dastgir’s protagonist struggles with depression. Faisal also has to contend with his mother’s advancing dementia as he negotiates a new relationship with fiancée Katie in middle age. Improvising with British apples in place of South Indian mangoes and a low oven flame instead of the midday sun, he makes apple pickle with his supportive blonde partner. More broadly, emphasis on the homecooked fits with the theme of food nostalgia, a thread that unspools across the anthology.

Bangladeshi sisters Mahruba T. Mowtushi and Mafruha Mohua showcase East Bengali dishes from ilish pulao and biryani to jackfruit with tamarind and Elokeshi pitha. In their story Jackfruit with Tamarind, all these dishes are viewed through the eyes of a young girl back in the ancestral village for a cholisha, the commemoration on the fortieth day of a loved one’s death.

In Hungry Eyes Pakistani-American novelist Sophia Khan examines a dystopian (or all too real) world of Us and Them. Amid this hostile realm, a pretentious Poetess makes egg sandwiches for refugees, while her son and she ostensibly search for her lost husband, the boy’s father.

Finally, in her Afterword: Dessert, the Forgotten Food research project’s Principal Investigator Siobhan Lambert-Hurley explains that her own preoccupation with Muslim South Asia originated with a penfriend mix-up and a mind-opening first taste of gajar ka halwa in her home country of Canada.

As Siobhan notes, ‘Creative writing becomes a vehicle, as in this book, for individual expression and gustatory memory’. In Desi Delicacies a multitude of flavours blend with love, joy, grief, regret, and memories. Eighteen accomplished storytellers not only create fine food writing but also serve up a rich helping of the histories and cultures of Muslim South Asia and its diasporas.