The road was generally somewhere in the Capital District of upstate New York. Think of it as a group of small cities and towns and centered on Albany, the state capital, Troy, where I lived at the time, and Schenectady, incidentally, where my grandfather had his first job in the United States, and where the band rehearsed in the basement of a photography studio in a somewhat sketchy part of town. The studio was owned by Rick Siciliano, lead vocalist and drummer for The Out of Control Rhythm and Blues Band. I played with the band from about 1985 or 86 to 1990 or so.

Not Exactly the Birth of the Blues

I am told that Siciliano started the band in the early 1980s as a means to attract women; I believe Duke Ellington was thinking the same thing when he decided to play piano. Rick got some of his buddies together to form a band. I hear he was better at attracting ladies than getting gigs. Somehow, though, he managed to gather reasonably good musicians. Chris Cernik joined on keyboards and served as den leader; he brought in his high school friend, John Eof on guitar. Then along came “Bad” Bob Maslyn on bass, Ken Drumm on alto and baritone sax to replace Rick’s buddy, Jimmy, and Rick Rourke on alto and tenor sax. There were others in and out of the band, Giles, some trumpeter whose name’s been forgotten, and then John Hines, who’d studied jazz trumpet at Berklee – that’s BerKLEE, the private music school in Boston, not BerKELEY, the flagship campus of the University of California.

They developed a repertoire organized around Blues Brothers tunes and Rick Siciliano’s taste in pop. They even had a couple of originals, “Lady DJ” (for Rick’s lust object du jour) and “Baby Tell the Truth.” Now we’re getting serious. Before you know it, Out of Control was getting gigs, but other bands were after John Hines. They put an ad in the local entertainment weekly, Metroland, looking for a substitute trumpet player.

I saw the ad, needed money, another tried and true motive for playing music. I called Ken, who acted as business manager, and set up an audition. I forget just how the audition process went, but it’s not like there were 30 trumpeters lined up to get the gig. Fact is, the time when trumpet was king was long gone by then so there weren’t many trumpeters, period. I forget just how I learned the tunes, but there were no charts. Perhaps Chris or Ken got me a set of rehearsal tapes. Whatever. I just listened and learned by ear, like all real musicians play, except for classical cats and other advanced miscreants. I soon became the one-and-only full-time trumpeter for the band.

On the Road

We played the majority of our gigs in the Capital District, but we did venture out on occasion. There was The Clubhouse at Pacer’s Restaurant up river in Glens Falls. Why we took the gig, I don’t know. Adventure, maybe. Anyhow, I once saw Mike Tyson fight in the arena there. The wedding in Wilton, Connecticut, was even further way; the bread was better, too. Turns out it was a quarter of a mile from Dave Brubeck’s place. Guess who showed up as a guest at the wedding? We spent a summer weekend, 1988, in Amagansett and Montauk out on Long Island. The beach was fine, mostly – saw discarded syringes in the sand near one bar. Unverified rumor has it that Jann Wenner heard us at Stephen Talkhouse in Amagansett; if so, he didn’t put us on the cover of his magazine. That wedding at the compound in the Adirondacks was a blast. Sound man extraordinaire Jim Boa put a wireless mic on my trumpet so I could stroll among the revelers. Americade at Lake George was surreal: 25,000 middle-age bikers paraded their touring bikes through town. Malcolm Forbes showed up in head-to-toe leathers while his crew wrangled the Capitalist Tool balloon. We were contractually obligated to perform “The Star-Spangled Banner.” I did it solo.

GE Plastics took us to Montreal in the dead of Winter, January 1987, and put us up in the Queen Elizabeth Hotel where they were holding their annual marketing meeting. Bought us white tails so we could play for the dancing pleasure of their male marketing mavens. They didn’t dance, alas. No women. Afterwards, we hauled ass to the open jam at DuDu’s House of Blues; it seems like half the blues guitarists in town lined up to sit in with us. Meanwhile, Bo Diddley had to borrow a guitar from us because, you know, airlines. Why drummer Rick had a guitar with him is a mystery.

We even did a cross-over gig in ‘89. Druis Beasley and her sister, Fonda, joined from the other group I played with at the time, the New African Music Collective. They sang back-up vocals at a gig sponsored by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Blues at the ‘Tute.

And toot we did, but as I said, mostly in clubs in the aforementioned Capital District. Saratoga Springs was at the northern edge of the district. One of our favorite clubs was there, The Metro. It was owned by Peter Paquette, a former art professor at Skidmore College who dressed a bit like Don “Miami Vice” Johnson as I recall. It had three venues: the downstairs bar, where we played; a disco behind that; and an upstairs room with a bar, tables with table cloths (but no food), and a jazz trio (classy). Between sets we could go hang out in the bar upstairs, check in at the disco, or, we could go outside to a glassed-in area festooned with tropical greenery, or, at any rate, a passel of cool plants with big leaves.

Why was The Metro one of our favorite clubs? The venue was nice, a bit larger than most of the bars and clubs where we played. Management – Peter Paquette – was cool, and so was the staff. The crowds were into the music. On a reasonable night they’d get up and dance, pretty important when the music is basically dancing music. On a good night, well, that’s something else indeed. As Rick Rourke once said about playing music: “It’s the closest you can get to really being, feeling totally happy with yourself.” He should know. He’d been at it full-time for a decade and a half before he took a job as a car salesman, for financial stability I assume. He joined Out of Control to keep in touch with the good life.

We liked to play five or so gigs a month, three weekends. Kenny would book a Metro gig every month or month and a half, Pauly’s Hotel in Albany (coming up in a minute), various other clubs as available, and a big money gig if he could arrange it, a wedding, corporate party, or even opening for a “name” performer (one of those coming up, too). He took particular care to book The Metro in August, which was racing season in Saratoga. Lots of people in town for the races. The Metro would be jammed, rich people, horse people, fugitives from the Philadelphia Orchestra, party people, out of control people. Well, not quite, we kept them on a leash, but a loose one.

For my money, though, the single best gig we ever played was at a scrappy sports bar in North Troy. What I remember is that, more than at any other gig we played, the crowd generated energy – whatever you want to call it – more than enough to answer ours and then some. All we did was cruise the energy flow, direct it here and there. Front and center was Lenny (RIP), a fan from The Blockhouse Beef and Brew, a Schenectady joint favored by a biker gang of Vietnam vets. Lenny fit the profile: shoulder-length hair, black leather jacket, wallet on a chain, blue jeans, scruffy black engineer boots. What I see in my mind’s eye is Lenny balanced on top of his Harley while spinning it around the dance floor shooting laser beams from his eyes and lighting up the crowd. I don’t think that actually happened. Doesn’t seem physically possible, does it? Metaphysically, yes. Actually physically, no. But one can never tell about these things.

Then there was that New Year’s Eve wedding at the Cranwell in the Berkshires. Rick Rourke (sax) and I drove together. There was just enough snow to elicit the Winter Wonderland vibe, but not so much as to make the driving treacherous. I loved wedding gigs, though many of the guys in the band seemed to be skeptical, perhaps because they didn’t like the idea of being a wedding band. But we weren’t a wedding band, and Ken made that clear when he booked the gig. We play our regular repertoire, no chicken dance, but we’ll learn a tune for the bride’s first dance. We do jazz-lite for the reception. That’s it, and you pay us an arm and a leg for the privilege. So the people were serious about dancing, and you always had three, maybe four, who knows, generations out on the dance floor.

Anyhow, the Cranwell one of those places known as cottages by the people who built and lived in them, but to you and me they’re mansions. Most of them are no longer private residences, too costly to maintain. The Cranwell was an event venue. I don’t remember much about the place, but there was a lot of dark wood paneling and a large parking lot full of Caddies, Benzes and an occasional Buick, maybe a Lexus.

As part of the deal we agreed to let the groom’s good buddy sit in on harp – that’s blues talk for harmonica, why, I don’t know. We were a bit iffy about this, because who the hell knew whether or not good buddy could actually play; but they’re paying the bill, so what choice did we have? It’s not like we’re Muddy Waters or the Rolling Stones. We’re just a bunch of local guys. Anyhow, buddy shows up with a case full of harps in every damn key, which could be a good sign or it could mean he just had some spare change and no sense. But when he took out his bullet mic, we began breathing again. A bullet mic is a small mic you can cup in your hand right up against the harp. He knew what he was doing.

A good time was had by all – though they did stiff us a bit on the meal. Soup. Pumpkin soup, freshly made, not canned, and sandwiches. But still, it wasn’t what they served the aunts, uncles, parents, grandparents, nieces and nephews (once, twice, trice removed), the friends from college, high school and everyone else who had some personnel connection, however tenuous, to the lucky bride and groom.

I suppose I should tell you about one of our big gigs, not opening for The Hooters in the Fieldhouse at RPI, though that was fun (I wore my white Lester Bowie lab coat so I could live up to my moniker, Doc). I’m talking about opening for B. B. King at The Palace Theater in Albany, New York, in September of 1986. Obviously it was a special gig. Perhaps some might even say it was an honor. But that’s not quite the right connotation. Honor? It’s a gig. The thing is, it’s not as though being local guys opening for one of the all-time greats somehow exempted us from actually having to show up and play our assess off. No, whatever else it is, it’s a gig like every other gig. You have to play the music, no matter what the venue or how big the crowd, you have to PLAY, otherwise what’s the point?

And that’s what we did. We opened with “Runnin’ Blue,” by Boz Scaggs, which opens with a horn line that’s high wide and screaming. Since I play the trumpet – about which Garrison Keillor has said, “Now there’s an instrument you can really embarrass yourself with” – it was up to me to put it over. Things were going great until the very last note, a high one. Nothing came out of the horn. Not a damn thing. Did I panic? Hell, no, couldn’t afford to. Besides, Chris was cranking it out over there on the Hammond B3 with the whirling Leslies; he covered the note. No one (in the audience) new that the trumpeter choked. Looked like I was wailing away. The gig went fine.

What I remember of King’s performance was maybe 30 seconds or a minute. It was in a slow blues late in the set, the volume was down, and King was singing about misery. And boy was he miserable. To hear him you’d think he was fixin’ to die right there on stage, just dissolve into a puddle of pulsating protoplasm. Then, all of a sudden, he snapped his head a quarter turn toward the audience and a flashed a big smile from ear-through-eyes-to-ear: Gotcha! Just as quickly, the smile disappeared and King’s pulsating protoplasmic perambulation continued.

Afterward we got to meet the Beale Street Blues Boy Himself. Must have appreciated the champagne Ken had sent up to his dressing room before the show. Still, we had to line-up along with all the middle-aged matrons in flower print dresses and wide go-to-church hats. B.B. had a good word for every one of them. Us too. Mike Tremante, our guitarist at the time: “You were there for me, B.B., nobody else was.” So he was, for all of us.

Pauly’s Hotel, How the Sausage is Made

Pauly’s Hotel was our core meat-and-potatoes gig in Albany. We liked to play there once a month or two throughout the year. It was a well-known entertainment spot. But don’t let the “hotel” fool you. There aren’t many rooms for rent – none you’d book through a travel agent. It’s mostly a bar with a small raised section at the rear where the stage is.

You pay a cover charge at the door, at least that’s how it worked back when I was there. I have no idea how they handle things in the world of smart phones and QR codes. But a beer is still a beer, right? The room is long and narrow with a high pressed-tin ceiling. That tin is historic don’t you know? So, you’ve paid the guy at the door and walk past the shuffle board table to your left and take a seat at the bar to your right. Or maybe you walk back to the rear where you go up a couple of steps and take a seat at one of those postage-stamp tables, you and your date. There’s just enough time to order a couple of drinks before the show begins.

The drummer, Rick Siciliano, fronts the band from center stage, horns to the right, bass, guitar, and keys to the left. “One, two, three,” and they’re into it, Tower of Power’s “You’re Still a Young Man.” The horn line is unmistakable. The trumpeter has it, high, wide, and wonderful and, and…blppzt!..cracks a note, what a buncha’ clams! The floor opens wide and he’s gone. The music keeps rolling. “You’re still a young man, babe uh ooh ooh, don’t waste yourrr time…”

That was the worst crash-and-burn of my musical life. Just fell apart. To make things worse, there was that hot blonde down front (with her husband, but a man can dream, no?), who’s been to see us before.

Later that night – likely not that night, but some other night when we were playing Pauly’s, but this is just a recollection, not gospel, so, for present purposes, it’s later that particular night – we were cresting the last set with a Sam and Dave tune, “When Something’s Wrong with My Baby.” Rick Rourke (alto sax) joins Rick Siciliano (drums) on vocals. Me and Ken have a simple back-up line. Now we’re into the third chorus, building up a head, I hear “Unchained Melody” out there, supporting the vocal. It wasn’t premeditated, it just floated of my horn. Redemption, for the opening clam roll, that’s what it was, redemption rolling down my forehead, my cheeks, my neck. Not, mind you, that anyone in particular was paying attention to my little drama, not the guys in the band, not the audience. It’s just the music.

I have no idea how many times we played Pauly’s in my five years with the band. Some shows better than others, some very good indeed.

Before there was any show, however, the roadies had to set up. Then we’d trickle in, get out our instruments, and warm up. There was a particular warm-up riff I’d taken to playing, not just on Pauly’s gigs, but on gigs in general. But something linked it in my mind to Pauly’s and I decided to extend the riff into a full melody. We came to call it “Jumping at Pauly’s.” Just how that happened isn’t clear. But it might have gone like this:

As the melody was fast and complicated, I imagine that Ken, Rick, and I got together and rehearsed before we took it to the band. I’m sure I wrote it out, probably gave a part to Ken, but Rick didn’t read music. He had to pick it up by ear, the sort of thing he’d been doing for years.

Somehow Bob Maslyn wrote some lyrics. Let’s say we ran down the horn melody in rehearsal a couple of times. Rick got a rhythm on the drums, Chris came up with a keyboard part, which was no problem since the tune is a straightforward up-tempo blues, and the same for Maslyn on bass and whoever was playing guitar at the time, I think it was Mike Tremante, though Mike Derrico played on the recording. I gave Bob a lead sheet so he could go off and work up some lyrics while I came up with some horn back-up riffs.

All this went into the next rehearsal. Siciliano made up his own melody for Maslyn’s lyrics, which was fine with me. The horn line was cool, but not very singable. Rick Rourke came up with some more back-up riffs and with a line we could use to transition into the solo section. An arrangement was slowly emerging from the primordial blues ooze. Drummer Rick counted it out: First the horn line as an introduction, then two full vocal choruses, transition to an alto sax solo, transition to a trumpet solo and then…I don’t know what happened. But it became magic. Maslyn found a nice five note ostinato bass line he liked and thumped away on it for just a bit. The band jelled around it and finished out the tune.

At the next rehearsal I moved that bass ostinato over into the horns so Bob could do his usual walking bass. Then Ken played a riff on his baritone, Rick added one on alto, I doubled it on trumpet, now it’s time to throw a guitar solo on top, and then a piano. What a loud, raucous, wonderful chaos. Here it is:

Once we got it tight in rehearsal, we played it on gigs. Once, twice, but by the third time it was getting a bit raggedy. We pulled it out of the rotation and took it back into rehearsal.

This wasn’t the first time. It happened a lot. You rehearse a tune ‘till it shines and then play it out. After a bit, though, it gets loose, crooked, and tarnished. Rehearsal is one thing, playing before an audience is another. The two situations call for different interaction and anticipation “settings” so it takes a while to get adjusted. It’s a subtle thing.

E pluribus unum

There are other stories I could tell you, lots of other stories. But I want to shift gears and say a bit more about the band itself, who and what we were. Above all else, and here I’m dead serious, we were musicians, making music together. Nothing else counted.

Outside of the band, we were very different. Chris Cernik, keyboards, was a lawyer to herded politicians as parliamentarian for the New York State Assembly. Ken Drumm, alto and baritone sax, ran a local ad agency. John Eof, guitar, owned a retail photography store. Drummer and lead vocalist, Rick Siciliano, was a commercial photographer who bought some of his supplies at Eof’s. “Bad” Bob Maslyn was a lawyer in private practice. I don’t know where the “bad” comes from. And Rick Rourke, alto and tenor sax and back-up vocals, he sold cars, and was very good at it, too. During my tenure with the band we had two more bass players and three more guitarists. One of these guys drove a route for a local beverage distributor and another was a computer programmer for some NY State agency. I don’t know what the others did nor how to assign jobs to people.

Every one of us had some clothes that were band clothes. We didn’t wear uniforms – except for that time when GE Plastics bought us white tails because someone had the silly idea that all those salesmen would actually dance without any women to dance with – but we did dress for gigs, each according to our own style. There was no formal leader. We all got paid the same. We paid the roadies more than we paid ourselves. Why? Because they had to work longer hours, that’s why.

Now, I say “we,” but it was Ken who did it. We didn’t hold a band meeting about it. Ken just did it, we all knew he did it, and we were fine with it – at least I think we were. He was the business manager. He booked the gigs, collected the money and then handed it out to the rest of us.

Chris ran the rehearsals. If he could wrangle politicians, then he could wrangle musicians. He also made up the set lists before every gig. Very important. We generally played three sets a night, with eight or so tunes per set. We need to open each set strong, and close strong. In between, you want to keep a nice flow while maintaining contrast between adjacent tunes. And then the solos. Gotta’ make sure the guys get their solo spots, otherwise they’ll be grumpy. See, a job for a politician.

It was up to Rick Siciliano to execute the set list. As I’ve said, he was our drummer and lead vocalist and, as such, he had to front the band. He’d talk to the audience, cue up the next song – perhaps call an audible every once in a while, and introduce the band in the last set. He loved it, fronting the band, the lights, the glory. That’s why he started the band.

And the rest of us, we played our parts. There were lots of tacit understandings going on. Had to be. No other way to make things work. Were there tensions and troubles? Of course, we’re human.

For example, me and Siciliano. He was Mr. Pop. Me, I come from a jazz background, had studied improvisation with Frank Foster, who’d played with Count Basie and Elvin Jones, and Sarah Vaughan, among others. I was a jazz soloist by inclination. Not much room for that in a rhythm and blues band, some, but not much. Rick would have been happier singing “Goddess on the mountain top, Burning like a silver flame” (“Venus,” by Bananarama). He did get us to play “Sledgehammer.”

Our differences never broke out into open contention, but there was an occasion. I forget the tune, but it was a slow blues, perhaps “Stormy Monday,” or perhaps “Ironweed Blues,” my tune. I was playing a nice solo, ‘cause I love a slow blues, and decided to go around for a second chorus, but Rick just drummed all over it. At least that’s how it seemed to me. I tossed my music across the stage – one of the few times we had a stage large enough for such a gesture – and walked off the stage. But I got back in time for the next tune.

Why? Why’d we put up with each other. For the music, that’s why. Listen to these Japanese school kids:

Listen to the soprano sax at 0:36, see her bow at 0:53. She’s absorbed in the music. They all are. They’ve become Musicians. It’s the same with seven ornery middle-aged guys playing rhythm and blues in upstate New York. For a moment we morph into Musicians and the Music. No more, but assuredly no less.

Like Rick Rourke said, “It’s the closest you can get to really being feeling totally happy with yourself.” It’s something bigger than yourself. A higher purpose? Don’t know what those words mean. I do know what music is.

Coda: Inside These Walls

For a decade and a half before he joined Out of Control, Rick Rourke had been a full-time musician playing in various rock and roll bands in upstate New York, including Merlin’s Minstrels, Emerald City, and Proto Foto. The Daley brothers were in Proto Foto as well. Frank, guitar, eventually spent ten years touring with Bo Diddley, but died unexpectedly in December of 2022. Jack, on bass, split for New York City in the late 1980s and ended up playing with Lenny Kravitz for 15 years. After that it seems like everyone got a piece of him, most recently Bruce Springsteen.

Back in 1970, though, when Rick was between bands, he and a friend decided to go to Florida. He put a harmonica in his pocket and off they went to Florida by way of Louisiana. Then this, then that, the cops pulled ‘em over, found some weed, and he ended up in the infamous Angola prison, officially known as Louisiana State Penitentiary. Fortunately they decided not to keep him. For a minute, though, it seemed like life was over. This song came out of that minute. Out of Control recorded it in 1996.

Rick’s retired now. He splits his time between Upstate New York and Florida and makes music all the time. You can find more of his music on Soundcloud.

Shameless Plug

I’ve written quite a bit about music for 3 Quarks Daily. Here’s a list of articles, with links:

- Black, White, and Blues: Notes on Music in America

- Dance to the Music: The Kids Owned the Day

- Thriving and Jiving Among Friends and Family: The Place of Music in Everyday Life

- Tell me about the blues

- Roll over Beethoven: Where’d classical music go?

My Early Jazz Education: From the Firehouse to Louis Armstrong - Sonic Transportation: It shook me, the light!

- Born to Groove: Up from Mud and Back to Our Roots

- Sukiyaki and beyond: Hiromi Uehara, music, war and peace, Chick Corea, and others

- Jacob Collier, a 21st Century Mozart?

- Connecting with the Jazz Tradition: Studying with Frank Foster in Buffalo

TwoSet Violin, the best thing in music education since sliced bread - An Improviser Is Born

- Wonderful Rainbow Aesthetics: The Song of Israel Kamakawiwo’ole

- Leapin’ Lizards: Three Lessons from Marching Band

- A look under the hood through the insane musical genius that is Mnozil Brass

- Louis Armstrong and the Snake-Charmin’ Hoochie-Coochie Meme

- Markos Vamvakaris: A Pilgrim on Ancient Byzantine Roads

- Ecstasy at Baltimore’s Left Bank Jazz Society

Break! How I Busted Three Trumpeters Out of a Maryland Prison - A White Blackman

- The Magic of the Bell and a Glimpse of Spirits

- Some Varieties of Musical Experience

- Charlie Keil: Groovologist

Beyond that, I published a book about music two decades ago, Beethoven’s Anvil: Music in Mind and Culture (the link takes you to Amazon, or Powell’s, where you can purchase a copy).

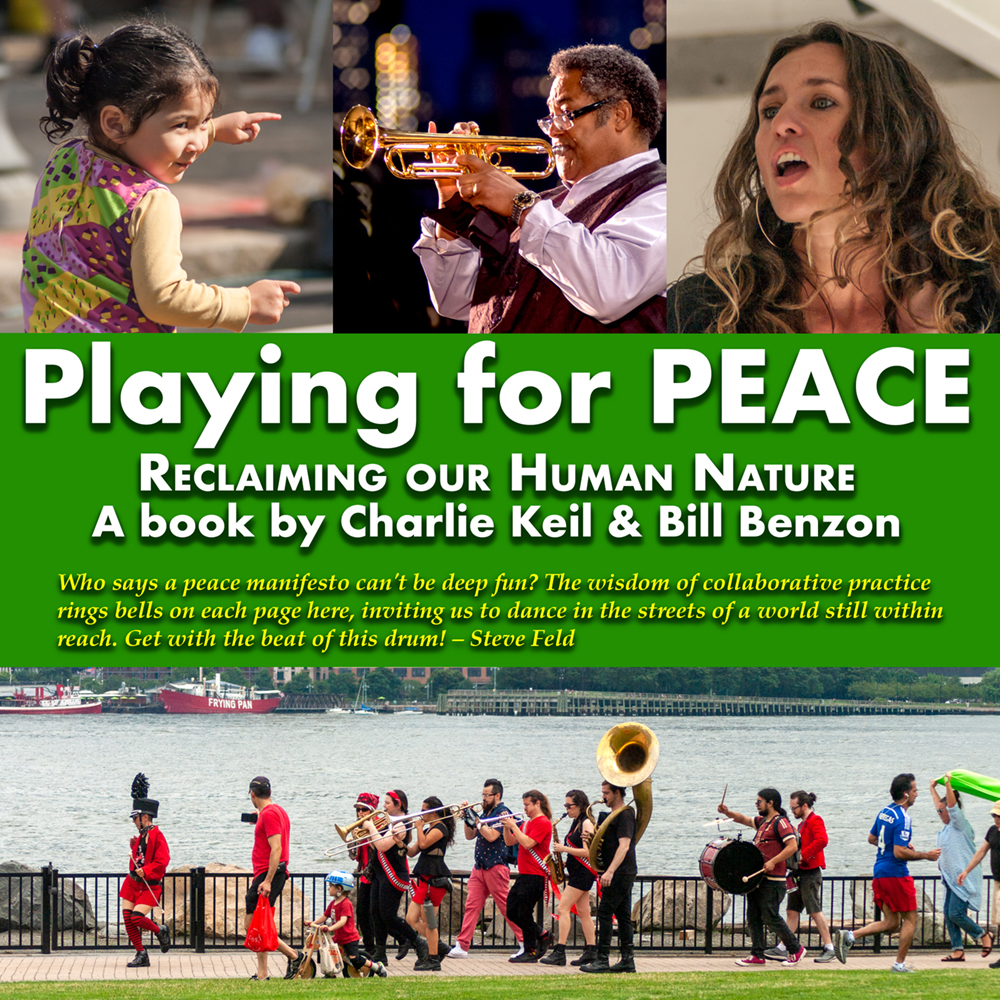

More recently, Charlie Keil and I have put together a collection of essays on music: Playing for Peace: Reclaiming Our Human Nature (Amazon, Barnes & Noble).