by Mary Hrovat

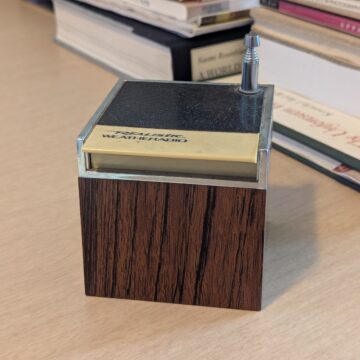

After my power went out during a recent round of severe storms, I turned on my battery-operated Realistic Weatheradio. I bought this cubical radio at Radio Shack many years ago, and it sits on a bookshelf in the living room, largely ignored until extreme weather happens along. It can be tuned to one of two wavelengths on which the National Weather Service broadcasts a loop of information on current and predicted weather conditions. It has a large, obvious on-switch; the two dials on the bottom are labeled “Tuning” and “Volume.”

When I turned the radio off after the storms had moved on, it occurred to me that it would probably look very old-fashioned to young people; I was thinking of my grandchildren and nieces and nephews. The sides are covered in wood veneer, a nod to the fact that radios used to be pieces of wooden furniture. I wondered if anyone else still uses a radio that you tune with a dial. For some reason, the radio was defamiliarized so that even to me it seemed to be slightly out of place in time. (I feel that way myself sometimes.) And it unexpectedly conjured an entire lost world.

I looked up the Weatheradio and learned that it was sold between 1982 and 1992. Realistic was a house brand of Radio Shack, which for many years sold consumer electronics. It was a standard fixture of malls in my youth, like Orange Julius and WaldenBooks. In 2015, the company declared bankruptcy, in part because it couldn’t compete well as the market for electronics—in fact, the nature of consumer electronics—changed dramatically. It changed hands several times and is currently an online business called RadioShack (losing a space in its name, among many other things). The only actual radios it currently sells are four models of a vintage three-band radio (AM, FM, shortwave). (So I guess there are other people who tune their radios using a dial.) It’s a familiar story, and it encapsulates one of the ways the world has changed in my lifetime.

I can’t remember when I bought my radio, but my life has also changed considerably since the decade it was on the market. Seeing the weather radio as a vintage object brought home to me how many things that used to be familiar have vanished. I don’t miss Radio Shack, or malls, and I don’t particularly mind that some of the more recent technology I use is now considered vintage. But sometimes it feels as if the world has moved on and left me behind. I’ve always been a bit of an oddball, but the world I learned to adapt myself to was the one I grew up in, and that world is largely gone. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013.

Sughra Raza. Seeing is Believing. Vahrner See, Südtirol, October 2013. It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

It’s a ritual now. Every Sunday morning I go into my garage and use marker pens and sticky tape to make a new sign. Then from noon to one I stand on a street corner near the Safeway, shoulder to shoulder with two or three hundred other would-be troublemakers, waving my latest slogan at passing cars.

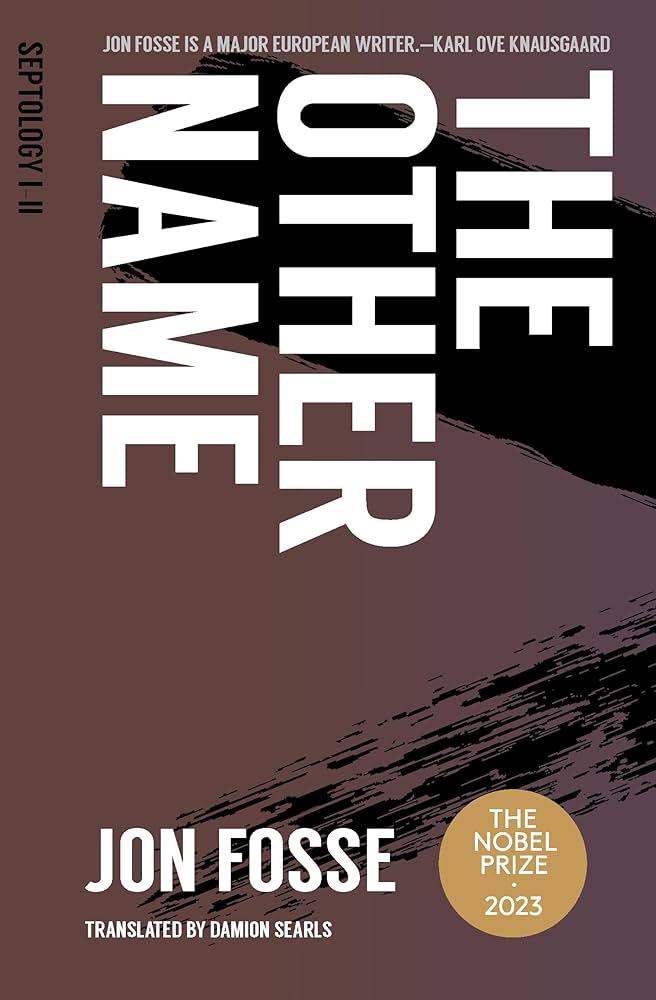

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

I first started reading Jon Fosse’s Septology in a bookstore. I read the first page and found myself unable to stop, like a person running on a treadmill at high speed. Finally I jumped off and caught my breath. Fosse’s book, which is a collection of seven novels published as a single volume, is one sentence long. I knew this when I picked it up, but it wasn’t as I expected. I had envisioned something like Proust or Henry James, a sentence with thousands and thousands of subordinate clauses, each one nested in the one before it, creating a sort of dizzying vortex that challenges the reader to keep track of things, but when examined closely, is found to be grammatically perfect. Fosse isn’t like that. The sentence is, if we want to be pedantic about it, one long comma splice. It could easily be split up into thousands of sentences simply by replacing the commas with periods. What this means is the book is not difficult to read—it’s actually rather easy, and once you get warmed up, just like on a long run, you settle into the pace and rhythm of the words, and you begin to move at a steady speed, your breathing and reading equilibrated.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.