by Rafaël Newman

At the University of Toronto one winter term in the mid-1980s I took an undergraduate course on classical philology. The instructor was Hugh Mason, a British-born Marxist who once reproved me for wearing a white dress shirt to give a presentation, something he maintained “only a fascist” would have done in his day. (My own politico-sartorial instructions, meanwhile, were issued by The Clash, who cautioned strongly against a wardrobe featuring the colors blue and brown unless one were already “working for the clampdown”). The course was spent for the most part learning about celebrated pioneers of the study of Greek and Latin—among them Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, better known beyond the world of classical antiquity for his dispute with Nietzsche—; but there was also a unit on something called Proto-Indo-European.

PIE, as it is commonly abbreviated, is the hypothetical “mother” of the large, widespread family of tongues comprising Greek, Latin, English, French, and German, but also Russian, Farsi, Lithuanian, Albanian, and Hindi, among many others. Their linguistic ancestor can only be theorized, following the discoveries of British colonial philologists in 18th-century India who compared Sanskrit with Ancient Greek: because there are no written records of languages spoken longer ago than a few millennia.

A putative PIE vocabulary, we learned from Professor Mason, must thus be reconstructed by surveying the modern languages identified as cognate descendants of the earlier idiom for similarly sounding words with related meanings—such as, famously, μήτηρ/mater/mère/Mutter/mother—and using established laws of phonetic evolution to reverse-engineer as their forebear *méh₂tēr (the subscript stands for a particular quality of aspirate, while the asterisk indicates that the word is hypothetical). The PIE reconstruction I recall best from the course, however, and which had no doubt been chosen (or perhaps invented) to reflect the climatic conditions in which we were gathering, in Toronto in February, was *sneghweti: “It is snowing”.

The study of Proto-Indo-European has developed considerably over the past 40 years, since I was first introduced to the idea that winter day in Toronto, its evolution driven by significant technological advances, particularly in the fields of archeology and genetics. In Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global, Laura Spinney gives an absorbing account of the latest attempts to identify and trace the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Spinney, a science journalist, surveys archaeologists, geneticists, and linguists who are reconstructing not only the way those prehistoric peoples spoke, but also how they lived. Read more »

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

In

In

In a recent essay,

In a recent essay,

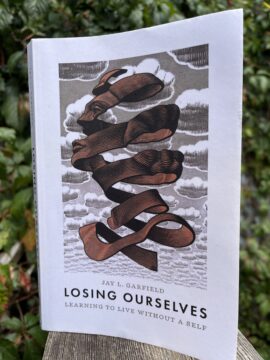

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.