by Eric Feigenbaum

In 2016, my then-wife and I took our one and three-year-old children from Los Angeles to Bali, Indonesia. It took 21 hours of flight time with one stop in Tokyo to refuel and another in Singapore to change planes – making for a roughly 26-hour journey with two kids in diapers. It is not the easiest way to begin a vacation.

My wife and I were seasoned travelers – both of us having lived abroad before meeting. Asia was no stranger to either of us, and in fact I had lived in both Bali and Singapore in my 20’s. There was a time in both our lives when the best flight was the cheapest one. When flying from Bangkok to Kathmandu for the first time with two buddies aboard Royal Nepal Airlines, we laughed about the used TV cart the flight attendants pushed through the aisle instead of the Boeing-issued ones – purposely included with the plane both for functionality and safety.

One British friend used to take Biman Airlines of Bangladesh back to London from Bangkok, sleeping on the floor of the Dhaka Airport in order to save the most money. Once on a budget flight from Bangkok to Udon Thani, there was so little leg room, I couldn’t sit forward and had to pivot to fit into the row.

It didn’t matter – it was part of the adventure and made for great stories.

Traveling with a one and three-year old across the world was an adventure in and of itself – and suddenly inconveniences were enemies and comforts our best friends. We needed any and every advantage we could get. It became clear to my wife and I that we had reached the age where reducing friction was worth a premium. We needed to rely on everything we couldn’t control going right.

After all, when something goes right, we often don’t notice or comment – but when it goes wrong, it becomes clear that “nothing” is really the hallmark of incredible accomplishment.

This is the bedrock success of Singapore Airlines. Read more »

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

The wealthy and powerful have always used the narrative to their advantage. The narrative defines them as superior in some way, and thus deserving of their power and wealth. In ancient times, they might be descended from the Gods, or at least favored by them or otherwise connected to them, perhaps through special communicative powers that granted them insights into the will of the Gods or God. In modern capitalist societies, that narrative promotes a fantasy of merit. You are rich and/or powerful because you are better. You are more civilized, better educated, more intelligent, or blessed with an exceptional work ethic. These narratives cast wealth and/or power as not only justifiable, but deserved.

In

In

In a recent essay,

In a recent essay,

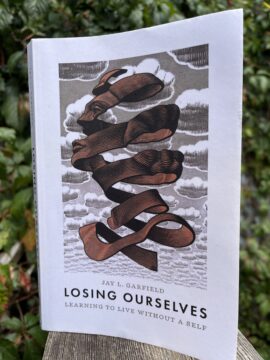

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

We’re living at a time when the glorification of independence and individualism is harming the world and others in it, as well as leading to an epidemic of loneliness. According to Jay Garfield, the root of suffering is in our self-alienation, and one symptom of our alienation is clinging to the notion that we are selves. “We are wired to misunderstand our own mode of existence,” he writes in his brief yet substantial 2022 book,

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.