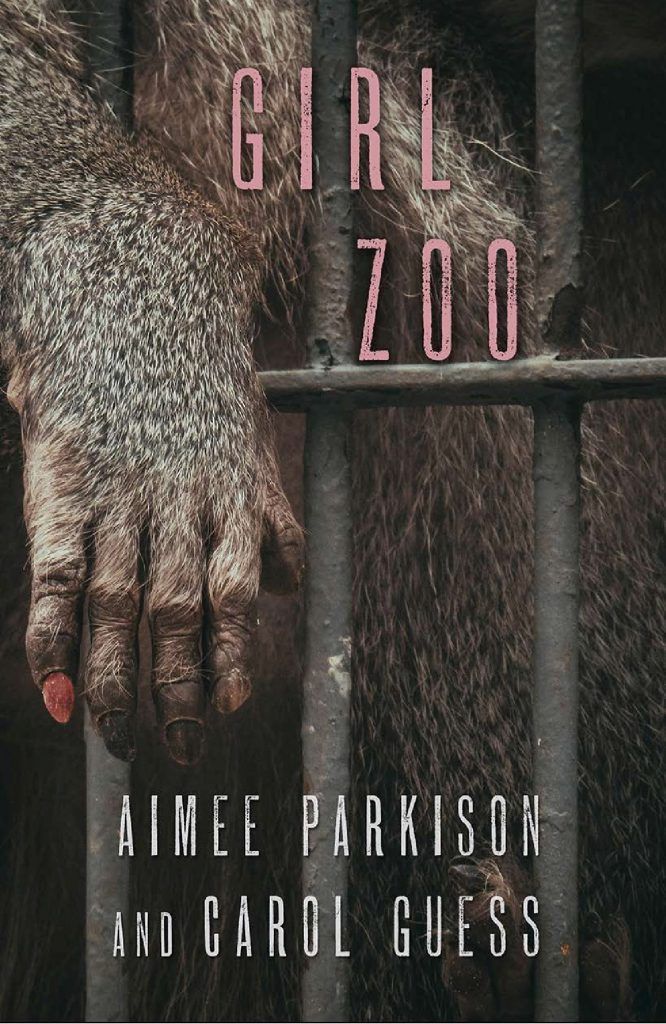

Andrea Scrima: Girl Zoo, which has just been published by the FC2 imprint of the University of Alabama Press, is a collection of stories that takes contemporary feminist theory on an odyssey through the collective capitalist subconscious. Scenes of female incarceration are nightmarish, hallucinatory: each story exists within its own universe and operates according to its own set of natural laws. But while there’s a fairy-tale quality to the telling, none of these stories departs very far from the everyday experience of institutionalized sexism: the all-too-familiar is magnified just enough to reveal its inherently devastating proportions.

Aimee, Carol, I wonder if we could begin by talking about the collaborative process. How did the idea come about to write a book together?

Aimee Parkison: As an artist, I’m always trying new things. I have a wide range and want to expand and explore. My creative process is vital to the way I experience the world. I like the excitement of a new project, a new idea. I write all sorts of stories, from flash fictions to long narratives, from experimental to traditional, from realism to surrealism. Some of my fictions are character-based and others more conceptual. I often focus on the lives of women and am known for revisionist approaches to narrative and poetic language. My writing is often categorized as experimental or innovative. I’ve published five books of fiction, story collections, and a short novel. I’ve been published widely in literary journals. Among my previous books are Refrigerated Music for a Gleaming Woman (FC2 Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize) and a short novel, The Petals of Your Eyes (Starcherone/Dzanc). I admire Carol’s writing and had interviewed her for a couple of articles I was writing for AWP’s The Writer’s Chronicle magazine. A year or so after the interview, she emailed me, inviting me to do a collaboration.

Carol Guess: My approach to writing came through music and dance. Years ago, I studied ballet and moved to New York to try to make a career in that world. Obviously that didn’t happen, but my early experience with failure made me determined to be good at something else! I’d always written for pleasure, so I began taking my writing more seriously, initially focusing on poetry. I did my MFA in poetry; I’ve never actually taken a class in fiction writing. I put my first novel together as an experiment. I wanted to teach myself how to write a novel, and so I did. Since then I’ve published twenty books, each one an experiment and a challenge. I’ll ask myself, “What would happen if …” and then set out to answer my own question.

My books range across genres. I’ve written novels, short stories, poetry, prose poetry, creative nonfiction, hybrid work, and most recently, plays. When I first began my writing career I had to really fight to be heard and recognized because my work was openly queer, with lesbian protagonists, something still overlooked by mainstream presses and literary prizes. My work focuses on queer lives, sexuality and gender, violence against women, and nonhuman animals. The only form I’m not interested in is journalism. I love reading the news, but I prefer to invent the stories I tell. I’ve been a dedicated reader of Aimee’s work for quite some time, so I was thrilled when she agreed to collaborate.

A.S.: How did the co-authorship of Girl Zoo actually take shape?

A.P.: Carol and I hadn’t met in person yet, and we didn’t have any idea for the book. I had never written a collaborative book before, so I was hesitant. Carol had written many collaborative books and had a process in mind that started with our brainstorming about concepts and ideas we both felt strongly about or had an interest in connected to our previous work. Then, once we had settled on the idea of “girl in confinement,” she suggested a process.

C.G.: The process emerged organically. I was thinking a lot about nonhuman animal rights, in particular Steven Wise’s work with the Nonhuman Rights Project. I’m haunted by ways that animals, including deeply intelligent animals like elephants and apes, suffer emotional and physical distress in confinement. I wanted to work with the idea of zoos as negative spaces, spaces of captivity and ensnarement, where animals are forced to engage with the public against their consent. Aimee and I had already established that we were interested in nonfiction accounts of abducted girls. We combined the two concepts, and Girl Zoo was born.

The actual practice of writing involved passing stories back and forth via email. We also wrote some solo pieces for the collection, but most of the pieces were shared. I’ve collaborated on a number of books, and what I’m always looking for is to expand my range, to learn from my collaborator. It was a pleasure to play with Aimee and to learn from her work. Collaboration is my classroom.

A.S.: Some of the stories present prevailing cultural narratives as cages in a kind of house of mirrors—romance, beauty, desirability—and so it’s not merely the everyday exploitative norms of sexist society that entrap women, but their own longings and expectations.

A.P.: That’s one of Girl Zoo’s themes. It’s complicated and scary to consider how romantic entrapment is glamorized for women and girls. Pop culture teaches girls that the greatest compliment for any woman is to be desired by someone more powerful, usually an alpha male. To be a model is to be a celebrated beauty, objectified in a fashion magazine, and trapped inside the gaze of strangers. Society sends messages to girls that they should long for cages disguised as mirrors. Girls compete with each other for the best cages because freedom is something unimaginable. Freedom is not feminine or ladylike. Agency is elusive when the girl zoo is all around us. We are trained to be caged or to lose our sense of womanhood. The pervasive, insidious, seductive beauty of cages feeds on iconic messages in fashion, photography, art, myth, fairytale, and pop culture.

C.G.: What I’ll add is that I’m obsessed with ways that women betray each other, as well as themselves. Yes, we live in a patriarchy, and need to direct our political energy toward fighting the battles patriarchy imposes on us, particularly right now, with women’s basic bodily freedoms under attack. But as a queer woman, I’m also sensitive to ways that women sometimes undermine each other, whether with overt cruelty and violence or, more commonly, through gossip, backstabbing, and shunning. I think women sometimes attack other women because it’s easier than trying to fight patriarchal power, which is as elusive as air. It’s in everything, it’s everywhere, so how can you really fight it? As a feminist and a queer woman, my heart is always broken when I see women diminish and damage each other. I’m not trying to be naïve; I believe in ambition, and I know that ambition sometimes requires winning over others, doing more, being better. I’m very ambitious. But I don’t throw other women under the bus. For example, “Girl in Perfume” was modeled on my experience in a toxic work environment where women bullied, shunned, and harassed other women while simultaneously calling themselves feminists. Shunning is especially interesting in this regard, and there are several instances of shunning and bullying between women in Girl Zoo.

A.S.: A few of the stories are heavily footnoted, adding a meta-narrative that is often facetious or sarcastic in tone, but sometimes feels more chilling, like the voice of an oppressive political authority. It adds a final layer of misogyny to the text, as though the patriarchy always gets the last word: belittling the subject of the story, calling the female narrator into doubt, ridiculing her, reinterpreting her words. Cancelling out her testimony, effectively disappearing her.

A.P.: Some of the footnotes have a confrontational element that borders on the sinister. We were trying to capture the experience of women’s voices being undermined. The footnotes undermine the text in a sometimes sinister, sometimes playful, and sometimes clinical, antagonistic fashion. Something about the way footnotes appear on the page lends itself to that as well—the smaller font appearing so low on the page, beneath the text, a sort of under-voice of authority undermining the female narrator.

C.G.: The footnotes were also meant as a way to engage with social media’s pervasiveness, the way our comments and actions and photographs leave a trail of personality. I’m not on Facebook, but I was once, and what I found was that the temptation to insert seemingly innocuous comments into every situation got people into trouble. The footnotes can be read old school, as footnotes in a book, or as a particularly vicious Facebook feed, or even the invisible hand behind Facebook, permitting speech in that forum that we wouldn’t permit face-to-face or in journalistic accounts.

A.S.: There’s a footnote on page 114 that suddenly became a key to the book for me. I’d like to quote it in full: “Debate continues between human and computer translators regarding the word ‘diggers.’ The computer translators believe that the word refers to ‘liking’ something—‘I dig blood sports,’ for example. The human translators believe that the word refers to gravediggers (…).” While you use the form of the footnote frequently in Girl Zoo, this time, it felt like a report from a not-so-distant future, from a “late America” in which the enslavement of women has become complete, and the prevalence of algorithms are on their way toward replacing human thought. The idea of translation is key here: this disturbing idea of the future imperfectly translating the past, lacking the essential ability to interpret it correctly, making the most obvious suffering even worse because it portrays it wrongly, falsifies it in retrospect. This is also, of course, a critique on our own interpretation of the past.

A.P.: That’s Carol’s innovation. She did a very cool thing with that story. It was one of the pieces I started (if I remember correctly). I had written the gothic surreal text of that story, and I knew it didn’t make for logical, transparent, accessible narrative. I liked the abstract poetry and its implications and decided to go with it. I was looking forward to seeing what Carol would do, since it was a collaboration open to weird experiments. I was wondering what Carol would make of the language-based surreal and somewhat nonsensical statements: where would she take them? I didn’t know. I didn’t really know where it was going. And Carol surprised me by going in another creative direction, adding another layer with this context in the footnotes that brought up the idea of a dystopian future where the text was a fragile artifact imperfectly translated, calling the voice into question due to the translation of a lost language and therefore explaining its inaccessible weirdness.

C.G.: Aimee and I had fun surprising each other with our responses. I’m glad you liked the footnotes to that piece; I intended them exactly as you experienced them.

A.S.: The piece “Girl in Knots” begins with the words: “Whatever you want. Whatever you want is what I want. Whatever you want is what I want and I want whatever you want. Whatever you want is what I want and I want whatever you want because you want it.” Could you talk a bit about the reference to R. D. Laing here?

C.G.: “Girl in Knots” wasn’t intended as a response to Laing’s work, although I see the parallels now that you point them out. I was interested in ways that women lose themselves in abusive relationships. I used the metaphor of the knot to represent emotional entanglement and coercion. There’s a pun on “tie the knot,” meaning to marry, but I was also using BDSM imagery in a context that drains it of healthy consent. I’m interested in consent and ways women navigate this form of self-knowledge. In an abusive relationship, consent unravels as one person takes control over another person’s ability to name their desires. In this story, I imagined both partners as female, but I wanted to leave the characters’ sexuality and gender up to the reader.

A.S.: There is a centerfold to the book, and I quote: “This piece should span the middle of the book, two pages opening flat like a centerfold. [. . .] Each body part should be photographed, outlined, examined, compared, cut, and then pieced back together again.” Were there moments when it was hard to write this book?

A.P.: Absolutely. Since part of the idea of females in confinement is that we’re often trapped by being objectified, we had to show how the female body could become a type of cage when advertised or displayed by a misogynistic society.

C.G.: I struggled emotionally writing “Girl in One-Act Play.” That was hard for me to research and write. But that’s unusual. Ordinarily I feel happy about the act of capturing my imagination in action. There’s a distance I’ve developed as a writer (do all writers experience this?) between myself and my material, even when elements of the material might be related to personal experience. Also, the book is funny where you least expect it. Writing humor is a way for me to detach from the pain of difficult material. That’s why I loved the film “Get Out.” To use humor and horror to speak the unspeakable – that’s art. That’s a level of brilliance I can only aspire to.

A.S.: I recently saw the big Nancy Spero exhibition at P.S. 1 in New York, and I became so absorbed by her 200-foot-long piece Notes in Time from 1979 that I had to go back and see it, or rather read it—because Spero uses a wealth of quoted text in the work—a second time. Triple Canopy did an online version of the scroll back in 2010. Spero quotes Artaud, Nietzsche, and Derrida, and finds everywhere misogyny resounding throughout the ages. In the way Clarice Lispector asks “Why this world?”, I find myself wondering why, throughout all of history, female subjugation became the essential factor in social organization. How do we explain our existence on this planet?

A.P.: There is no life without women.

This conversation marks my one-year anniversary as columnist for 3 Quarks Daily. I’ve talked to Madeleine LaRue about the Swiss writer Peter Bichsel; Liesl Schillinger about literature and politics; and Saskia Vogel about sex, pornography, and her debut novel Permission. There’s also a conversation with Myriam Naumann that explores the connecting points between my book A Lesser Day and an installation I exhibited several months back at the Berlin gallery Manière Noire, titled “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire.”

The series can be found in its entirety here.

My next 3Quarks conversation, which will appear on September 9, will be with the artists Eve Sussman and Simon Lee.