by Danielle Spencer

Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

The film opens a soundscape, memoryscape, landscape—and a bodyscape, all of us in the vast hall sloping gently down towards the screen like a nighttime jungle floor. The opening scene is still, close and quiet, and then there is a very loud sound, which startles me. It also startles Jessica (Tilda Swinton) who awakens in surprise. I am anxious that there will be more surprising loud sounds. Then Jessica rises and sits in a room of the house. She looks at what in my memory is a small bright aquarium in front of the windows, warmly lit with orange fish. The space and sound around the aquarium are dark and oceanic.

In the opening passages of Austerlitz (W.G. Sebald) the narrator travels by train to Antwerp. He finds his way to the zoo and sits beside an aviary full of brightly feathered finches and siskins fluttering about, and then visits the Nocturama, peering at the creatures in their enclosures, leading their sombrous lives behind the glass by the light of a pale moon. He returns to the waiting room of the Centraal Station, remarking that it ought to have cages for lions and leopards let into its marble niches, and aquaria for sharks, octopuses, and crocodiles, just as some zoos, conversely, have little railway trains in which you can, so to speak, travel to the farthest corners of the earth. As the sun sets and the light dims in the station waiting room, he sees the waiting travelers in miniature, as the dwarf creatures in the Nocturama.

When I was ten my father and I spent the spring in Budapest, where he proved theorems at the Institute of Mathematics and I was enrolled in the Kodály music school. Our small apartment building was near the top of a hill on the hilly western Buda side of the city, home to several mathematicians and their families. Some nights we went up the street to eat schnitzel at the restaurant on the corner.

András, the mathematician who lived with his family and their little loud dog Brumi in the ground-floor apartment, often ate early so he didn’t have to listen to the accordion player who arrived during the dinner hour. At school I couldn’t understand much apart from the music, so I listened to the sounds of my teachers and classmates speaking Hungarian and read novels borrowed from the American embassy library, which I reached by metro after school, the red line running through a deep tunnel under the Danube.

In April we took a hydrofoil up the river to Vienna and attended a production of The Magic Flute at the State Opera. We were in a box on the left-hand side of the horseshoe-shaped theater. Papageno the bird-catcher trilled in his green feathers in the glowing bright cuboid stage, a large bird cage on his back. I felt achingly pulled towards the full space between us all in the darkened hall, each of us in our small red velvet enclosure, seeing and hearing together. I felt this again last night. I also felt my shoulder stiffening painfully; my nose dripping behind my face mask; my body, older now, larger in my seat, unused to holding so still after so many months out of public spaces.

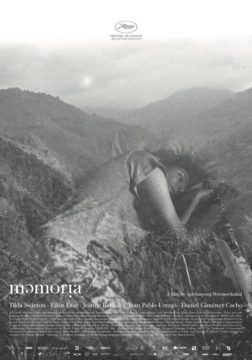

In the theater we hear the mysterious loud noise as Jessica does, though the other characters in the film evidently cannot hear it. Jessica, a Scottish botanist living in Colombia, describes it to an audio engineer and musician, Hernán, who patiently re-creates it, based on her description (it’s like a rumble, from the core of the earth, and then it shrinks) so he then hears a version of it as well. She meets an archaeologist (Jeanne Balibar) who shows her a 6,000-year old skeleton unearthed by an enormous tunnel excavation in the Colombian jungle. Seeking the source of the sound, we travel with Jessica to the tunnel site—worker ants dwarfed by the tunnel into the earth, with their rumbling machinery—and then meet a much older Hernán (Elkin Díaz). Jessica seems to be experiencing Hernán’s memories, as we are—and as you ( ) are mine.

As Jessica and Hernán sit together they stop speaking, and all sounds stop.

There and then we are aware of the silence in this large space, and the space between us, our own bodies and those next to us, listening to what the silence of the pandemic has permitted us to hear as the world has quieted around us, each in our box listening for the Proustian narrator’s convent bells, which are so effectively drowned during the day by the noises of the street that one would suppose them to have stopped, until they ring out again through the silent evening air. Jessica approaches the window and we look out into the jungle. Dwarf creatures in the Nocturama, we travel together through space and time, through subterranean tunnels on little railway trains to the farthest corners of the earth, finding, now, a creature unlike any we have seen before.