I live in Hoboken, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from Midtown Manhattan. I have been photographing the irises in the Eleventh Street flower beds since 2011. So far I have uploaded 558 of those photos to Flickr.

I took most of those photos in May or June. But there is one from April 30, 2021, and three from April 29, 2022. I took the following photograph on Monday, April 15, 2024 at 4:54 PM (digital cameras can record the date and time an image was taken). Why so early in April? Random variation in the weather I suppose.

That particular photo is an example of what I like to call the “urban pastoral,” I term I once heard applied to Hart Crane’s The Bridge.

Most of my iris photographs, however, do not include enough context to justify that label. They are just photographs of irises. I took this one on Friday, April 19, 2024 at 3:23 PM.

It was a cloudy day. I took the shot from below, pointing the camera at the sky. To do that I had to bend down and hold the camera beneath the flower, pointing obliquely upward. Since I couldn’t look through the view-finder at that angle I had to take the shot blindly. Sometimes you get an interesting shot, sometimes you don’t.

Why do I love irises? I was certainly influenced by my mother. As I said in an earlier article about irises: “I remember my mother kneeling in front of the flower bed. Brown slacks. Heavy gloves. She was breaking up the ground and weeding the bed. Her flowers.” She taught me how to weed the bed, something I haven’t done in decades.

Why did my mother love irises? Because they’re beautiful? Wherein does their beauty reside? Has it a purpose, a function?

I decided to ask ChatGPT why flowers had blossoms. Here’s how it replied:

Flowers have blossoms primarily for reproductive purposes. The blossom, or flower, is the reproductive structure of flowering plants, also known as angiosperms. Its main function is to facilitate the process of pollination, where pollen from the male parts (anthers) is transferred to the female parts (stigma) of the same or another flower, leading to fertilization and the production of seeds.

The attractive colors, shapes, and fragrances of blossoms are adaptations that have evolved to attract pollinators such as bees, butterflies, birds, and bats. These pollinators are essential for the transfer of pollen between flowers, ensuring successful fertilization and the continuation of the plant species.

While one must be on the lookout for confabulation, that agreed with my prior knowledge, so I accepted it at face value. I then asked ChatGPT: Since blossoms exist to attract pollinators, and humans find blossoms attractive as well, would it be reasonable to conclude that we share a sense of beauty with those pollinators? Here’s the last paragraph of its answer:

While humans and pollinators may not share identical perceptions of beauty, there’s certainly a convergence in our appreciation for certain aspects of the natural world, including the beauty of blossoms. This shared appreciation may be rooted in evolutionary and ecological dynamics that have shaped our sensory preferences and behaviors over time.

That’s good enough for me. But then I’m prejudiced.

However, our sense of beauty is surely shaped by culture as well. Vincent van Gogh’s paintings of irises are well-known. In 1987 one of them, simply titled “Irises,” sold for $53.9 million, becoming the most expensive painting ever sold. I believe that it has since dropped down in that list.

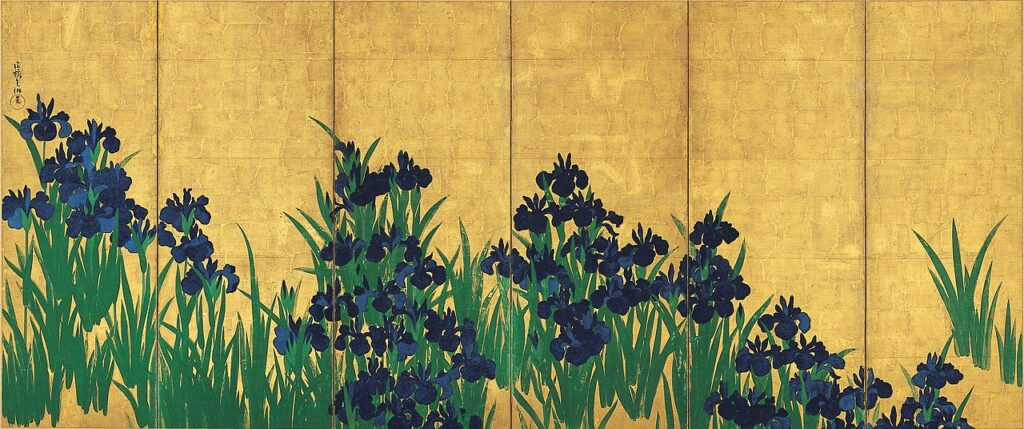

Van Gogh, in turn, is known to have been influenced by Japanese ukiyo-e prints, where irises have been a common subject for several centuries. Irises are also the subject of two well-known sets of screens by Ogata Kōrin from the early 18th century. Here’s a panel from the earlier of the two sets, held by the Nezu Art Museum in Tokyo.

Those screens were, in turn, based on an episode in The Tales of Ise.

Thus we have a circuit that goes roughly like this: Plants and pollinators interact to produce iris blossoms (among many other kinds of blossoms). These blossoms attract the attention of many humans, who find them pleasing. Among them we have Japanese print and screen makers and Vincent Gogh. All of them have, in turn, acted in concert to please 100s and 1000s and 10s of 1000s of others in the contemporary world, including me and my mother.

Why not send it for another spin around the merry-go-round? Last month I asked ChatGPT to transform a Wallace Stevens poem, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” into one about an A.I., which it did. If it could do that, surely it could do the same for irises.

And so it has.

I.

Among twenty blooming irises,

The only stirring thing

Was the flutter of a butterfly.

II.

I was of three minds,

Like a garden

Where there are three irises.

III.

The iris swayed in the spring breeze.

It was a small part of the dance.

IV.

A gardener and a sunbeam

Are one.

A gardener and a sunbeam and an iris

Are one.

V.

I do not know which to admire more,

The elegance of petals

Or the subtlety of colors,

The iris blooming

Or just before.

VI.

Raindrops adorned the petals

With delicate jewels.

The silhouette of the iris

Danced upon them, back and forth.

The feeling

Traced in the silhouette

A mystery beyond words.

VII.

O wise gardeners of old,

Why do you dream of other flowers?

Do you not see how the iris

Swirls around the stems

Of the flowers beside it?

VIII.

I know the language of flowers

And the undeniable pulse of nature;

But I know, too,

That the iris is entwined

In all that I comprehend.

IX.

When the iris swayed out of view,

It marked the boundary

Of one of many moments.

X.

At the sight of irises

Dancing in the sunlight,

Even the cynics of beauty

Would pause in wonder.

XI.

She strolled through the garden,

Lost in thought.

Once, a joy overcame her,

As she mistook

The scent of the blooms

For irises.

XII.

The breeze is stirring.

The iris must be swaying.

XIII.

It was morning all evening.

It was blossoming

And it was going to blossom.

The iris stood

In the garden’s embrace.

I suppose one might ask whether or not that poem is a “real” poem and, if so, is it as good as a human could do. That question, after all, is on many people’s minds these days: Are they as good as us? Better perhaps? Will they replace us, displace us? (Annihilate us?)

Those particular questions aren’t on my mind at the moment. They don’t compute, if you will. I don’t know what they mean.

Ever since GPT-3 came out my position has been that these are strange beasts, not like anything we know. Not like us, but not like other machines either. It’s going to take a while to think through these things, to make arrangements, to arrive at a modus vivendi.

In one respect the most recent large language models ARE superior to any human: they can generate coherent text on a much wider range of subjects than anyone can. Some of that text, however, may be fabricated. But WE do that as well. Yet it’s not that breadth of capability that we find problematic, not as long as it doesn’t exceed human ability in this or that specialized respect.

Of course computers have long been able to do many things better than we can, arithmetic calculation for one. Record keeping, sorting, and tabulation for another. But those are “routine” skills and so longer count, though there were times when they were very challenging tasks indeed. Back in the mid-1990s a computer beat the world’s best chess player, and computers have been doing that ever since. They beat us at Go as well. I believe that poker has now fallen. And it seems that AlphaFold has licked the protein-folding problem. But those are all specialized domains. As such they are no longer included in this game of “who’s the smartest of them all?”

I have no idea how that game will eventually work out. My guess is that we’ll see more and more specialized systems solve problems than humans have been working on for years. As for the most general case – Will there one day be a computer that’s smarter than the smartest human ever? – I suspect that question is ill-posed and therefore unanswerable. In time we’ll come up with better questions, along with ways to go about answering them. Just when this will happen, I don’t know.

Let’s return to irises, and ChatGPT’s imitation of Wallace Stevens. In what way does that poem resemble an iris?

Like any text, spoken or written, it is a string of words. It doesn’t appear that way on the page, where it is organized in a rectangular array. But we read through it one word, one phrase, at a time. That’s how we speak it, that’s how we hear it.

Often, though, when we write texts, we’ll plan them out, making notes, outlines, drafting paragraphs, whole sections, and so forth. Sure, there are occasions when we’ll just sit down and write it out from beginning to end. That’s generally how we write letters, or at least that’s how I’ve done it all my life, even the several-typed-pages long-letters that I wrote decades ago. But mostly texts of more than minimal size and complexity are planned out ahead of time.

That’s not how ChatGPT works. While its inner operations are obscure, we do know that it generates one word at a time. No notes, outlines, or drafts. Just word after word after word. Each time it’s a word that’s appropriate to the immediate context. Just how such a procedure results in a coherent overall text is something of a mystery.

How does an iris come into being? Like all living things, it starts with a single cell. That cell divides into two, those cells divide in turn, and so on until a full-grown plant emerges, complete with gorgeous blossoms having complex three-dimensional shapes. At each step of the way, the division of cells has only local guidance.

We like to think there is a design, some kind of overall plan, and that it is encoded in a DNA molecule. But we don’t quite know how that works. We do know, however, that the DNA molecule is one long string of “words” called codons. Step by step by locally-guided step, that string produces irises. It is in that way real irises are like ChatGPT’s poem about irises. At heart, they are strings.

The analogy is, I admit, a loose one, one involving a bit of intellectual slight-of-hand. Let me offer a last analogy, another bit of prestidigitation.

Consider a simply connected maze, which is one without any loops. If you are lost somewhere in such a maze, no matter how large and convoluted it may be, there is a simple procedure you can follow that will take you out of the maze. You don’t need to have a map of the maze; that is, you don’t need to know its structure. Simply place either your left or your right hand in contact with a wall and then start walking. As long as you maintain contact with the wall, you will find an exit. The structure of the maze is such that that local rule will take you out.

To summarize: a local rule will take you out of a maze. ChatGPT uses a local rule to create a poem (or any other text). Biological development uses local processes, guided by strands of DNA, to produce mature organisms. The weather is like that as well. No one plans or guides it. It just happens, tracking local conditions. In all cases: Local rules span global complexity.

As I began, the irises are blooming early this year.