by Claire Chambers

At the time of writing President Donald Trump is an inpatient at the Walter Reed Medical Center. He is of course receiving treatment for coronavirus, a virus he has repeatedly downplayed as being ‘like the flu’. Influenza causes a temperature, achy muscles, often a headache, and some upper respiratory tract symptoms such as a cough. Transmission is through droplet spread, handling of passive vectors like objects and surfaces, and physical contact with the infected. To be fair, this does sound rather like Covid-19, but it is there that the similarities end. Flu is a completely different virus, from which people mostly recover within a week. By contrast, with SARS-CoV-2 it is often in the second week of the illness that some sufferers become alarmingly sick. Influenza tends to kill younger people, because they sometimes have an overactive immune response to the virus leading to organ failure. Meanwhile, one of the reasons for the particular concern for Trump (out of all the Republicans who became infected in the last extraordinary week) is that it is old, obese men who are most at risk of dying. Thinking about the similarities and differences between influenza and Covid-19 brings me to two contemporary pandemic novels by women writers.

‘Changed utterly’: The 1918 Flu in Emma Donoghue’s The Pull of the Stars

Irish-Canadian author Emma Donoghue sets her latest novel The Pull of the Stars in Dublin against the backdrop of the final year of the First World War and the ‘Spanish Flu’ that killed more people than had died in the conflict. The intriguing creation story behind this publication is that Donoghue was almost at the proof-checking stage when the Covid-19 pandemic took hold globally. With the help of her publishers (Picador in the UK, and in America Little, Brown), the book was brought out quickly, and she was able to count on a readership sadly better educated about pandemics than she ever expected.

Irish-Canadian author Emma Donoghue sets her latest novel The Pull of the Stars in Dublin against the backdrop of the final year of the First World War and the ‘Spanish Flu’ that killed more people than had died in the conflict. The intriguing creation story behind this publication is that Donoghue was almost at the proof-checking stage when the Covid-19 pandemic took hold globally. With the help of her publishers (Picador in the UK, and in America Little, Brown), the book was brought out quickly, and she was able to count on a readership sadly better educated about pandemics than she ever expected.

In the novel, the Easter Rising of 1916 is a recent memory, and a violent campaign for Home Rule or complete independence for Ireland is in full swing. Also in the background is the Suffragettes’ achievement of enfranchisement for older, property-holding women. In the momentous year of 1918, unmarried midwife Julia Power is turning thirty and will therefore be getting the vote. Julia hardly has time to reflect on this new power, as it were, and she is none too worried either about her ‘spinster’ status as she enters her fourth decade, for she is working intensively on the makeshift ‘Maternity/Fever’ ward at the local hospital. Nor does this diligent nurse have time for the Sinn Féiners’ politics. However, Julia’s engrained political quietism is shaken when a ‘lady rebel’ from the republicans’ ranks, Dr Kathleen Lynn (the only historical figure in this novel), impresses her as they work side by side on the ward. Less ambivalent than her nationalism is Julia’s commitment to women’s uplift. At one point a casually sexist orderly Groyne says that women haven’t died for the Great War as the male soldiers have. Her ire raised, Julia bites back that they have, and on this very maternity ward. Indeed, Donoghue’s visceral novel is full of empathy for the suffering of women – particularly poor women – when they experience stillbirths, domestic violence, or the ill treatment of unmarried mothers and their ‘bastard’ children.

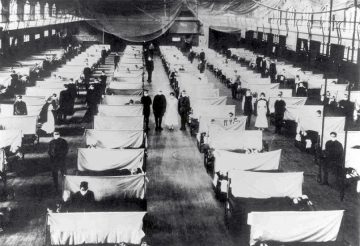

When Donoghue writes, ‘The old world was changed utterly, dying on its feet, and a new one was struggling to be born’ she knowingly echoes W. B. Yeats’s ‘Easter, 1916’ with its famous lines, ‘All changed, changed utterly: | A terrible beauty is born’. The Pull of the Stars demonstrates how utterly the world has changed, with mass gatherings being cancelled, face masks appearing ‘like the beaks of unfamiliar birds’, and coughs rousing panic: ‘Sure you might as well spray us with bullets!’ People find themselves ‘afraid to go near each other, it [the virus] can pounce so fast’. Julia is contemptuous of governmental edicts which victim-blame the ‘weakest of the herd’ for catching the flu and vacuously recommend the eating of onions as a prophylactic. Julia views such advice as nothing but propaganda: ‘This new flu was an uncanny plague, scything down swaths of men and women in the full bloom of their youth.’ Among these young victims are expectant mothers, who if they succumb to the malady are prone to pregnancy complications, premature labour, or even death. Julia herself had the grippe mildly early on in the epidemic. Her own assumed immunity while other hospital staffers fall sick means that Julia’s annual leave is cancelled. She works tirelessly to help the infected mothers-to-be on the short-staffed Fever/Maternity ward.

As mothers and premature babies are dying and only a quarter of the usual workers can perform their shifts at the hospital, Julia asks desperately for more hands on the ward. She is  sent Bridie Sweeney, a complete novice of a runner in her early twenties. This working-class slip of a girl is so uneducated about the details of reproduction that she mistakes baby bumps for podginess and fails to understand the word ‘maternity’. But she proves a quick study, and over the course of three days Julia teaches the young woman nursing and grows close to her. Spending time together outside the hospital too, Julia registers that following the combined impact of the war and the pandemic, ‘Dublin was sinking into dilapidation’ and ‘civilization might grind to a halt’. Yet there are also notes of optimism about a new ‘normal after the pandemic’ and the thought that ‘even this flu will […] run its course’. This last idea that ‘[t]he human race settles on terms with every plague in the end’ is confirmed when compassionate Bridie makes a discovery. She finds out that Julia’s antagonist Groyne is as misanthropic and, especially, misogynistic as he is because he had suffered in a previous outbreak of disease, having lost his wife and children to typhus.

sent Bridie Sweeney, a complete novice of a runner in her early twenties. This working-class slip of a girl is so uneducated about the details of reproduction that she mistakes baby bumps for podginess and fails to understand the word ‘maternity’. But she proves a quick study, and over the course of three days Julia teaches the young woman nursing and grows close to her. Spending time together outside the hospital too, Julia registers that following the combined impact of the war and the pandemic, ‘Dublin was sinking into dilapidation’ and ‘civilization might grind to a halt’. Yet there are also notes of optimism about a new ‘normal after the pandemic’ and the thought that ‘even this flu will […] run its course’. This last idea that ‘[t]he human race settles on terms with every plague in the end’ is confirmed when compassionate Bridie makes a discovery. She finds out that Julia’s antagonist Groyne is as misanthropic and, especially, misogynistic as he is because he had suffered in a previous outbreak of disease, having lost his wife and children to typhus.

What most interests me about this novel is that while in the coronavirus crisis military metaphors like ‘battling’ the ‘invisible enemy’ on the ‘frontline’ are commonly used, in 1918 a pandemic was raging even as a world war came to an end. When visited by such a major virus outbreak – as with the war that was expected to be over by Christmas 1914 but which dragged on for another four years – blithe optimism is futile; we are in it for the long haul. Moreover, the world that emerges from the wreckage will bear little resemblance to the normalcy remembered with nostalgia. Reading Emma Donoghue’s The Pull of the Stars drives home both these messages that all is changed, changed utterly.

‘O thou side-piercing sight!’ The Georgia Flu in Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven

‘O thou side-piercing sight!’ The Georgia Flu in Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven

Envisioning a future flu pandemic is a fascinating dystopian novel, Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven. This book is so prescient, especially given that it was published as early as 2014. The Canadian author describes a deadly pandemic which causes complete temporal rupture, the ‘divide between a before and an after’. As the narrative voice graphically puts it:

There was the flu that exploded like a neutron bomb over the surface of the earth and the shock of the collapse that followed, the first unspeakable years when everyone was traveling, before everyone caught on that there was no place they could walk to where life continued as it had before and settled wherever they could, clustered close together for safety in truck stops and former restaurants and old motels.

In St John Mandel’s story universe this strain of influenza that erupts with the force of an atomic bomb is a vicious variant of swine flu. Known as the Georgia Flu, the illness kills off the vast majority of the world’s inhabitants. (It should be noted that in this highly global text, the Georgia in question is the country in the Caucasus, not the state in the deep south of America.)

One of the most interesting aspects of Station Eleven is the way it looks back on the lifestyle before the pandemic from the vantage point of a devastated landscape twenty years on. Survivors can scarcely believe the old world that used to exist and was so full of affluence, commercial air travel, theatre shows, and relaxed social interactions (sound familiar?).

Not coincidentally, this pandemic novel is largely set in Toronto. That was one of the cities in which the original Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic erupted in 2003 but was soon quashed. In fact, memories of SARS-CoV-1 give characters false confidence. For instance, Jeevan’s girlfriend scoffs at his concerns about the Georgia Flu, recalling, ‘They made such a big deal  about it [SARS], then it blew over so fast.’ Yet the new flu is highly contagious. People get paranoid about ‘who had touched the door’ before them. Key workers first become ‘overwhelmed’ by an influx of the sick and dying they struggle to help, and are then themselves infected by the virus, falling mortally ill. Jeevan’s friend Hua, who works at the hospital, phones to urge him to ‘get out of the city’ and escape the contagion. But Jeevan can’t escape because of his disabled brother. Instead he takes to panic-buying from supermarkets, before holing up in self-isolation with his wheelchair-bound sibling. It is hard not to see this ‘blood-drenched’ time and the depressed ‘Year Twenty’ after the disaster as eerily prefiguring and exaggerating our experiences in 2020.

about it [SARS], then it blew over so fast.’ Yet the new flu is highly contagious. People get paranoid about ‘who had touched the door’ before them. Key workers first become ‘overwhelmed’ by an influx of the sick and dying they struggle to help, and are then themselves infected by the virus, falling mortally ill. Jeevan’s friend Hua, who works at the hospital, phones to urge him to ‘get out of the city’ and escape the contagion. But Jeevan can’t escape because of his disabled brother. Instead he takes to panic-buying from supermarkets, before holing up in self-isolation with his wheelchair-bound sibling. It is hard not to see this ‘blood-drenched’ time and the depressed ‘Year Twenty’ after the disaster as eerily prefiguring and exaggerating our experiences in 2020.

By the novel’s Year Twenty, though, those still living, as well as their children who had known no other way of life, have come to feel that ‘survival is insufficient’. Some of them realize the ‘importance of art’ for elevating themselves above mere existence. Accordingly, my epigraph to this section is taken from William Shakespeare’s King Lear and is a quote that bookends the novel.

The first ‘side-piercing sight’ readers are exposed to is the collapse on stage of the allusively-named actor Arthur Leander while he is performing the lead in Lear at a Toronto theatre. A former paparazzo and aspiring paramedic in the audience named Jeevan Chaudhary leaps to his aid and starts administering CPR. However, Arthur has suffered a massive heart attack and Jeevan is unable to revive him. Looking on in horror is an eight-year-old child actor, Kirsten Raymonde, who will never forget this traumatic experience. The interwoven lives and fates of these and other characters are explored through analepsis and prolepsis as this complex and multi-layered novel unfolds. Arthur’s demise is followed swiftly by the collapse of civilization, as the Georgia Flu spreads like wildfire around the world.

The first ‘side-piercing sight’ readers are exposed to is the collapse on stage of the allusively-named actor Arthur Leander while he is performing the lead in Lear at a Toronto theatre. A former paparazzo and aspiring paramedic in the audience named Jeevan Chaudhary leaps to his aid and starts administering CPR. However, Arthur has suffered a massive heart attack and Jeevan is unable to revive him. Looking on in horror is an eight-year-old child actor, Kirsten Raymonde, who will never forget this traumatic experience. The interwoven lives and fates of these and other characters are explored through analepsis and prolepsis as this complex and multi-layered novel unfolds. Arthur’s demise is followed swiftly by the collapse of civilization, as the Georgia Flu spreads like wildfire around the world.

One of Arthur’s three ex-wives is the wild-haired Miranda, whom the then-28 year-old actor had met as a teenager from Delano (the same small Canadian island from which he hails), in what is a clear nod to The Tempest. Miranda is an artist who is writing a graphic novel entitled Dr Eleven. This novel, which gives rise to St John Mandel’s own title, circulates and takes on great significance after Miranda’s horrible death from the virus in Malaysia mere hours after hearing the news of her ex’s own virus-free passing.

Meanwhile, suffering from amnesia, young Kirsten somehow survives the flu. Still passionately thespian, she joins a wandering group of players known as the Traveling Symphony. Their motley  crew perform musical recitals, as well as plays such as Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet, to sometimes aggressive fellow survivors across North America. This affords the actors much debate about the relevance (or its lack) of Shakespeare to their current situation. While some see his plays as aspirational – ‘People want what was best about the world’ – others are less enthusiastic. A clarinet-player, who will later go missing, ‘hated Shakespeare’ and ‘found the Symphony’s insistence on performing Shakespeare insufferable’. Her colleagues try to persuade her that because the Bard lived with no electricity in the time of bubonic plague and possibly lost his son Hamlet to the disease, his writing is appropriate for their post-apocalyptic times. (Recently the Guardian published an article speculating that King Lear might have been written while Shakespeare was living under a lockdown not dissimilar to ours in 2020.) Similarly, Susan Watkins, in her monograph Contemporary Women’s Post-Apocalyptic Fiction, argues that in this novel ‘the plays of Shakespeare become a positive symbol of the palimpsestic text: one that is inclusive can be transformed locally in performance’. Yet the clarinet-player is unpersuaded, retorting that ‘the difference was that they’d seen electricity, they’d seen everything, they’d watched a civilization collapse, and Shakespeare hadn’t. In Shakespeare’s time the wonders of technology were still ahead, not behind them, and far less had been lost.’

crew perform musical recitals, as well as plays such as Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet, to sometimes aggressive fellow survivors across North America. This affords the actors much debate about the relevance (or its lack) of Shakespeare to their current situation. While some see his plays as aspirational – ‘People want what was best about the world’ – others are less enthusiastic. A clarinet-player, who will later go missing, ‘hated Shakespeare’ and ‘found the Symphony’s insistence on performing Shakespeare insufferable’. Her colleagues try to persuade her that because the Bard lived with no electricity in the time of bubonic plague and possibly lost his son Hamlet to the disease, his writing is appropriate for their post-apocalyptic times. (Recently the Guardian published an article speculating that King Lear might have been written while Shakespeare was living under a lockdown not dissimilar to ours in 2020.) Similarly, Susan Watkins, in her monograph Contemporary Women’s Post-Apocalyptic Fiction, argues that in this novel ‘the plays of Shakespeare become a positive symbol of the palimpsestic text: one that is inclusive can be transformed locally in performance’. Yet the clarinet-player is unpersuaded, retorting that ‘the difference was that they’d seen electricity, they’d seen everything, they’d watched a civilization collapse, and Shakespeare hadn’t. In Shakespeare’s time the wonders of technology were still ahead, not behind them, and far less had been lost.’

Indeed, the wonders of technology are an issue of key concern in this Xennial’s switched-on novel. For the most part St John Mandel is a cheerleader for tech. She writes elegiacally about unchargeable phones and tablets in the post-electricity landscape, which defunct devices had once acted as ‘portals into a worldwide network’. Although she acknowledges the ‘Alone Together’ social isolation caused by what she calls ‘iPhone zombies’, the gadgets are nonetheless deeply missed when they become unusable. So much so that Arthur’s oldest friend Clark begins a Museum of Civilization, helped by donations of passports, drivers’ licences, phones, and laptops from fellow flight-castaways, at the airport where they are hiding out and building a new community. (This chimes with another dystopian novel, Naomi Alderman’s The Power, which is interspersed with an audio guide for the Museum of Post-Cataclysm Artifacts.)

‘[W]here was the internet?’ bewails Jeevan at one point. But there is one aspect of that ‘information age’ that he does not mourn. That is the world of the spitefully intrusive, amoral, and misogynistic TMZ and other ‘celebrity-gossip magazines’. Jeevan used to earn blood-money from such outlets in his work as, first, a paparazzo, and later an entertainment journalist. St John Mandel understands the necessary compulsion to earn money, but pours scorn on this industry’s vacuous obsession with rich, famous, and/or beautiful individuals such as Arthur Leander and his lovers and exes. Small wonder that soft-hearted Jeevan doesn’t last in this milieu, longing to do ‘something that matters’. Around the time order disintegrates, he has left celebrity gossip behind for a career as an ambulance man.

‘[W]here was the internet?’ bewails Jeevan at one point. But there is one aspect of that ‘information age’ that he does not mourn. That is the world of the spitefully intrusive, amoral, and misogynistic TMZ and other ‘celebrity-gossip magazines’. Jeevan used to earn blood-money from such outlets in his work as, first, a paparazzo, and later an entertainment journalist. St John Mandel understands the necessary compulsion to earn money, but pours scorn on this industry’s vacuous obsession with rich, famous, and/or beautiful individuals such as Arthur Leander and his lovers and exes. Small wonder that soft-hearted Jeevan doesn’t last in this milieu, longing to do ‘something that matters’. Around the time order disintegrates, he has left celebrity gossip behind for a career as an ambulance man.

Greater ambivalence is reserved for the loss of social media, as St John Mandel envisages a world of:

No more Internet. No more social media, no more scrolling through litanies of dreams and nervous hopes and photographs of lunches, cries for help and expressions of contentment and relationship-status updates with heart icons whole or broken, plans to meet up later, pleas, complaints, desires, pictures of babies dressed as bears or peppers for Halloween. No more reading and commenting on the lives of others, and in so doing, feeling slightly less alone in the room. No more avatars.

Sandwiched between two snappy sentences, the word salad in the middle ranges from the sublime to the ridiculous in a way that neatly evokes the incongruous juxtapositions of cyberspace. While social media can help fulfil hopes and dreams, connect the sociable or the afflicted, and combat loneliness, it also offers banal distractions, a space to boast or obfuscate, and a two-dimensional rendition of human relationships. St John Mandel seems to harbour mixed feelings about this particular off-shoot of technological development.

Even though it is ‘planes full of patients zero’ that led to the Georgia Flu’s rapid spread, St John Mandel’s characters rhapsodize about ‘the beauty of flight’. Surprisingly for a novel published in  2014, this techno-optimist has nothing to say about the environmental advantages of the aeroplanes’ grounding. What is regretted is that ‘[t]he world’s become so local’, communities hermetically sealed off from one another after travel becomes arduous and dangerous in the post-apocalypse.

2014, this techno-optimist has nothing to say about the environmental advantages of the aeroplanes’ grounding. What is regretted is that ‘[t]he world’s become so local’, communities hermetically sealed off from one another after travel becomes arduous and dangerous in the post-apocalypse.

Towards the end of the novel, we circle back to the quotation, in a flashback to the actor who plays Edgar to Arthur’s Lear pronouncing the line, ‘O thou side-piercing sight’. In King Lear’s context, Edgar says this to express his horror at the old man’s deteriorating appearance and evident madness. Yet in the novel, the sight that causes such anguish is the countless human deaths and destruction of an entire way of life. Treading the boards in Toronto, Edgar speaks these words to Gloucester. The narrator explains in what reads like a laconic stage direction that the actor playing Gloucester ‘would die of exposure on a highway in Quebec’ a week after this performance.

Side-piercing, indeed.