by Thomas O’Dwyer

A book subtitled A Novel of the Plague might appear opportunistic at this time. But in Maggie O’Farrell’s new and much-praised Hamnet, the only opportunity the author seems to be taking advantage of is our ignorance of the life of William Shakespeare. “Miraculous,” The Guardian wrote, “a beautiful imagination of the short life of Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, and the untold story of his wife, Agnes Hathaway, which builds into a profound exploration of the healing power of creativity.”

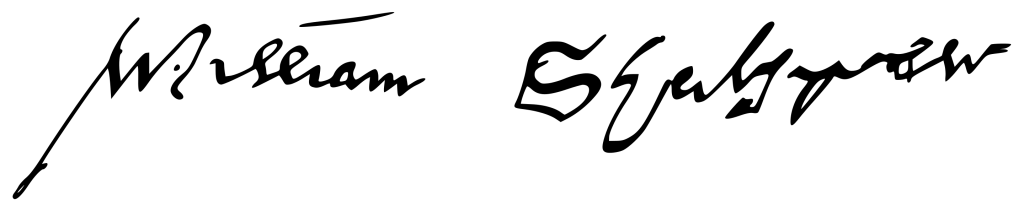

Around the world, library shelves creak under the weight of books, some centuries old and in a babel of languages, about England’s undisputed greatest genius. Analyses of his works aside, all that is written about the life and character of the man is speculation, fabulation or infatuation. A pencil and a postcard suffice to jot down the facts we know. Sifting through his plays and sonnets for clues to his life, beliefs and relationships will not do – though it has been done ad nauseam. The names Hamlet and Hamnet appear to have been interchangeable in documents dating from his time. Therefore, it must follow that William named his great play in memory of his only son Hamnet who died at the age of 11. That is one great burden of proof to place on the swapping of two letters, n and l, in one word.

A striking feature of O’Farrell’s novel is that the name Shakespeare appears nowhere, although it is entirely about the family of the playwright, a shadowy figure who slips in and out of his native Stratford-Upon-Avon.

“Everyone thought the glover’s son would amount to nothing, what a wastrel he had always seemed, and now look at him – a man of consequence in London, it is said, and there he goes, with his richly embroidered sleeves and shining leather boots.”

It is tempting to respond with Petruchio explaining in The Taming of the Shrew why he moved to Padua:

Such wind as scatters young men through the world,

To seek their fortunes farther than at home

Where small experience grows.

But there we go again, drawing conclusions from random quotes from the man’s theatre world. This novel is not the young man’s viewpoint or biography. Its theme is of women in the roles their times dictated for them. It chronicles their emotions and desires, their sorrows, their work and their ferocious protection of their children in a world where “the man” is absent, but nonetheless makes sure to provide money and a comfortable home for his family, as Shakespeare did.

The central figure in Hamnet is Agnes, the name the author prefers for Anne Hathaway, whom Will married in 1582, when she was 26 and pregnant, and he just 18. Her life revolves around providing for her children, Susanna, born six months after she married, and the twins Hamnet and Judith, who came two years later. In the background of the rural town’s daily life lurks the grimmest of silent reapers, the black death pandemic, which first threatens the life of young Judith but instead suddenly sweeps away her beloved twin brother.

Since the novel was written before the arrival of Covid-19, there is no pandering to our present crisis, yet the medieval plague in Hamnet feels menacing and startlingly immediate. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, theatres were shut down again and again to prevent the spread of infection and the main countermeasures were quarantines and social distancing. Physicians wore a dark leather hood and mask over a long gown to visit the sick, but had no idea what caused the plague or how to cure it. Eyeholes were cut into the leather and fitted with glass, and an evil-looking curved beak protruded from the face, holding fragrant compounds and herbs they believed would filter out the “sick air.” A long wooden stick completed the doctor’s protective gear, which he used to lift the bed covers and clothes of patients being examined. Despite their ignorance and failure to cure victims, people held these physicians in high regard and praised their courage and compassion.

Fake rumours and cures were everywhere, as were the charlatans who peddled them for profit. In 1665, the well-meaning English College of Physicians recommended sulphur fires to be “set plentiful against the bad air” that caused the plague and also recommended tobacco smoking for everyone, even children, to protect the lungs. Religious charms and amulets were ubiquitous in the credulous religious era. In London at times of greatest panic, quarantine was ruthlessly enforced. Any house where a plague victim had been present was sealed shut for 40 days – the door was locked and marked with a large red cross. During outbreaks, the city of London published statistics of people who had died each week. In 1593, 20,000 people in London died of the plague and new waves of the disease continued for two decades.

If you were fearful but well-off, tricksters would beat a path to your door offering costly exotic potions – powdered unicorn horn, frogs legs, crushed emeralds (real, of course), or simply mysterious cures like plague water or magical compounds with no explanation of what they contained. More deadly substances like mercury or arsenic powder at least had the advantage of killing the victim more quickly than the black death. And yet, even in this medical grifters’ paradise, there is no record of anyone being offered bleach injections or “light introduced inside the body” as remedies. Such is four centuries of progress.

The first part of O’Farrell’s novel moves from 1596, in the days before Hamnet falls ill, to a flashback of the meeting and marriage of his parents. Agnes Hathaway is no meek medieval wench but a powerful woman exuding knowledge, mystery and some menace, her closest friend a trained hawk – “the daughter of a dead forest witch … too wild for any man.” Her meeting with young Will results in a robust and passionately written sexual tryst in an apple storeroom. The second part of the novel follows them past the anguish of the boy’s death and on to Agnes’ presence at the staging of the tragic play that echoes Hamnet’s name, with her husband playing the ghost. “An arm’s length away, perhaps two, is Hamlet, her Hamlet, as he might have been, had he lived, and the ghost, who has her husband’s hands, her husband’s beard, who speaks in her husband’s voice.”

The novel is written in the present tense, dragging the reader minute by minute through every raw and sensual emotion on the page. The style is dense and lyrical and defiantly breaks a cardinal rule of every creative writing class, “kill the adjectives, murder your darlings.” O’Farrell’s approach is why use one adjective or metaphor where four will do. It takes some getting used to and male readers may be tempted to sniff that this is woman’s writing, dripping sentiments and scents and sensuousness all over the chintz furniture.

“The smell of his grandparents’ home is always the same: a mix of woodsmoke, polish, leather, wool. It is similar yet indefinably different from the adjoining two-roomed apartment, built by his grandfather in a narrow gap next to the larger house, where he lives with his mother and sisters. The two dwellings are separated by only a thin wattled wall but the air in each place is of a different ilk, a different scent, a different temperature. This house whistles with draughts and eddies of air, with the tapping and hammering of his grandfather’s workshop, with the raps and calls of customers at the window, with the noise and welter of the courtyard out the back, with the sound of his uncles coming and going.”

The overload of sensations can start to feel tiresome, overdone, like American concerned insincerity. But O’Farrell is no lazy or overwrought writer; her control is steady and masterful and the prose comes into its own with stunning effect at important points in the narrative. As we approach Hamnet’s unexpected death, it would be a hard man indeed, especially a father, who failed to shed a tear.

“All at once, he stops shaking and a great soundlessness falls over the room. His body is suddenly motionless, his gaze focused on something far above him …

Agnes bends forward to touch her lips to his forehead. And there, by the fire, held in the arms of his mother, in the room in which he learnt to crawl, to eat, to walk, to speak, Hamnet takes his last breath. He draws it in, he lets it out.

Then there is silence, stillness. Nothing more.”

That subtle echo from his father’s play is hard to miss and hard to take: “The rest is silence.”

Stephen Greenblatt, the Shakespearean scholar and editor of The Norton Shakespeare has written that “to understand how Shakespeare used his imagination to transform his life into his art, it is important to use our own imagination.” O’Farrell uses her imagination brilliantly to transform Will’s art into his life without even mentioning his name. It is quite possible to read this novel as a standalone fiction of a typical middle-class English family struggling through their lives in the 1590s in the shadow of a silent and lethal pandemic. No knowledge of Shakespeare’s world is required (although spotting elusive allusions to the plays is a pleasure), and no conclusions about his life and family need be drawn.

If the book has a theme that resonates today, it is the fragility of life. This was a constant refrain that past generations knew well before the discoveries of medical science. At least in the wealthy modern nations, we had forgotten this stark existential reality before the shrouded novel coronavirus showed up. “Then as now, commerce and travel are the engines of disease,” The Washington Post’s Ron Charles wrote in his review of the chapter in Hamnet where O’Farrell tracks the paths of the plague from Mediterranean Europe to rural England. “A glassmaker in Venice, a monkey in Alexandria, a cabin boy from the Isle of Man — they all play small but consequential roles in the intricate chain of transmission as infected fleas jump from body to body, sowing illness across Europe. It’s a fascinating and horrific demonstration of the same forces now driving a different pandemic more than 400 years later. We may have better medical technology, but our frantic missteps sound like echoes of the Renaissance.”

O’Farrell has said in an interview that she could not bring herself to write about Hamnet until her own child had passed his eleventh year. Any parent who has felt that chill primitive dread upon hearing of the death of some child the same age as their own will get that. Agnes Hathaway’s mother died in childbirth, her husband’s sister died in childhood, his mother lost two children before he was born. And then Hamnet. The novel effortlessly connects us again to the tragedy of Hamlet and reminds us of its family grief and anguish, from the prince’s father to Ophelia, Polonius, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and Yorick. Ghosts, controlling fathers, lost sons, disregarded daughters and lovers. And then Hamlet. Human voices cry out in anticipation of death, and then from beyond the grave after it. Cynics have said that the title Hamlet didn’t immortalize Hamnet – it just made him a typo. But O’Farrell suggests that Will took all those endless bereavements and forged them into immortal art.

Those who argue a direct link between the death of Hamnet and the play named for him often gloss over the fact that four years separated the two events. If Hamlet was an outpouring of grief for a dead son, it was a deferred one, recollected in tranquillity. During those years, Shakespeare wrote such lighthearted plays as The Merry Wives of Windsor, Much Ado About Nothing, and As You Like It. It seems unlikely then that Hamlet was a heartfelt response to Hamnet’s death, once again showing the folly of trying to reconstruct the life of the Bard (or any artist) from his work. Shakespeare may not have published any direct words about his feelings, but he did write touchingly about grief. In King John (1596) a mother describes the agonising pain of losing a son:

Grief fills the room up of my absent child

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me,

Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words,

Remembers me of all his gracious parts,

Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form.

O’Farrell’s book may pique such speculation about the mysteries buried in the Holy Trinity Church of Stratford where the Shakespeare family lies. But she offers none of it herself and the novel is all the more marvellous for its absence. It is simply a glowing picture of the marriage of a fascinating couple, a searing evocation of their family torn by grief, and a motherly memoir of a nice little boy who has been dead and forgotten for 424 years. Out of the mists of the 16th century, we feel the rattle of pandemic death; in our tech-complex world, we get the same reminder of our looming mortality as did the good, flawed folk of rural Stratford.

They are all gone into the world of light!

And I alone sit ling’ring here;

Their very memory is fair and bright,

And my sad thoughts doth clear.