by Mark R. DeLong

“People tell me that I could do much better,” David McCullough said in an interview included in California Typewriter, a documentary about typewriters “and the people who love them.” “I could go faster and have less to contend with if I were to use a computer—a word processor—but I don’t want to go faster. If anything, I would prefer to go slower.” He liked the straightforward mechanism of his Royal Standard Typewriter that he bought, used, in 1965 for about twenty-five dollars. “To me, it’s understandable: I press the key and another key comes up and prints a letter on a piece of paper and then you can pull it out. It’s a piece of paper upon which you have printed something.

“You’ve made that. It’s tangible. It’s real.”

That tangible quality, that reality comes clear in Richard Polt‘s Typewriter Manifesto, which concludes with a series of contrasts of typewriter life and digital life (using the red and black colors of some typewriter ribbons):

We choose the real over the representation,

the physical over the digital,

the durable over the unsustainable,

the self-sufficient over the efficient.

And then the manifesto concludes, “THE REVOLUTION WILL BE TYPEWRITTEN” of course.

Keyboards are keyboards, you might say. It’s the fancy stuff behind them that matters. Typewriters also have had their incremental improvements, electrification being the most obvious and, less obvious perhaps, the improvements on font rendering. The old fashioned levered hammer bearing the inverse shape of letters gave way to ingenious “balls” as in the IBM Selectric and “printwheels” that look like a miniature, heavy-duty bicycle wheel with spokes that bear the letters. (My own old typewriter has this technology.) These innovation allowed for font changes and vastly improved print typesetting. That story about the ingenious QWERTY keyboard layout minimizing key jambs and speeding production of words? I’d say, probably false. A more likely reason for that innovation was probably a simple marketing trick: a salesman who didn’t know how to type could still peck out T-Y-P-E-W-R-I-T-E-R using only the letters on the top row. Read more »

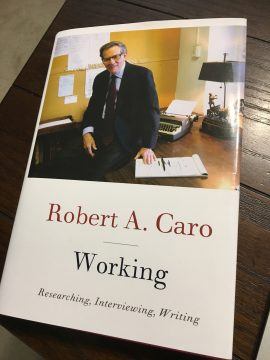

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.