by Andrea Scrima

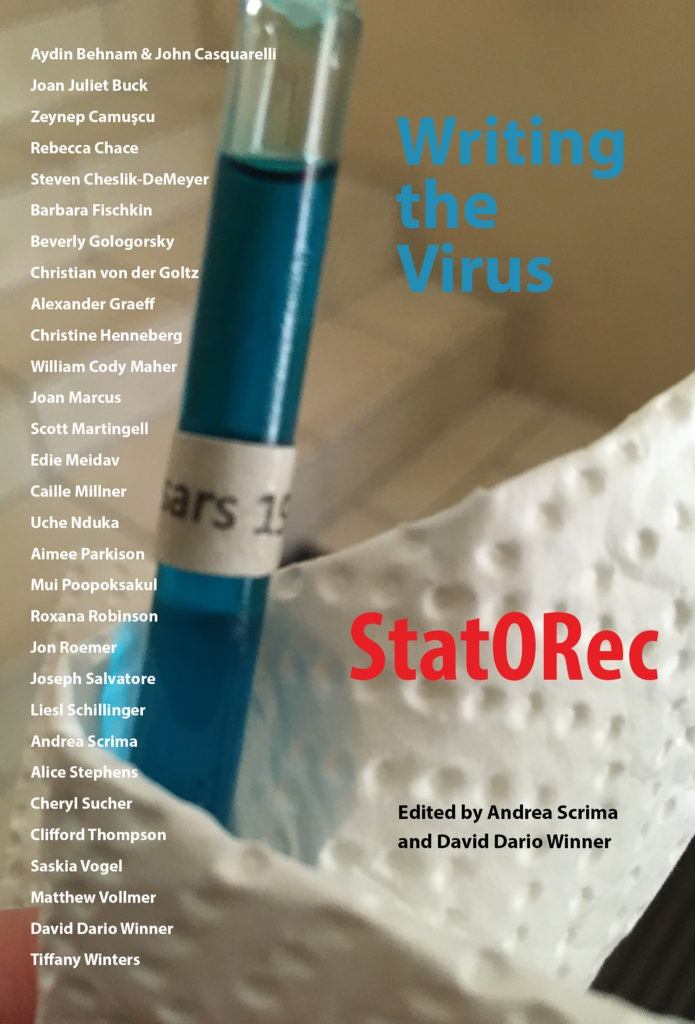

An anthology I’ve edited with David Winner, titled Writing the Virus, has just been published by Outpost19 Books (San Francisco). Its authors—among them Joan Juliet Buck, Rebecca Chace, Edie Meidav, Caille Millner, Uche Nduka, Mui Poopoksakul, Roxana Robinson, Jon Roemer, Joseph Salvatore, Liesl Schillinger, Andrea Scrima, Clifford Thompson, Saskia Vogel, Matthew Vollmer, and David Dario Winner—explore the experience of lockdown, quarantine, social distancing, and the politicization of the virus from a wide variety of perspectives. The majority of the texts were written exclusively for the online literary magazine StatORec, and a keen sense of urgency prevails throughout, an understanding that the authors are chronicling something, responding to something that is changing them and the social fabric all around them.

The range of this anthology is broad: there’s a haunting story that explores the psychological dimensions of an anti-Asian hate crime with a curiously absent culprit; hallucinatory prose that gropes its way through a labyrinth of internalized fear as human encounters are measured in terms of physical distance; a piece on the uncomfortable barriers of ethnicity, civic cooperation, and racism as experienced by someone going out for what is no longer an ordinary run; and a jazz pianist who listens to what’s behind the eerie silence of the virus’s global spread.

Writing the Virus includes a historical essay on the post-Cold War militarization of the police and the racist roots of police brutality; poems that probe racism’s dark and violent undercurrent in American society; a piece written as a response to the Black Lives Matter protests that reflects on Covid, Malcolm X, lockdown, and discovering a new room within to make one’s voice heard; and an essay that appeals to the power of love in the Black community as our strongest and most promising force for change. There are also essays about the beginnings of the pandemic and on the Bergamo/Valencia soccer game in Milan, the biological bomb that led to the virus’s rapid spread throughout northern Italy; about masks and guns that capture America in all its dangerous absurdity in a cops and robbers game gone horribly wrong; and essays that examine lockdown in disabled housing, women’s increasing vulnerability to mental and physical pain during and after abortion procedures, the unsavory sentiments behind one of America’s most-cherished narratives, the conquest of the West, as well as new motherhood as it reconfigures the geometry of transatlantic family ties in times of pandemic.

The works in this collection regard the virus and the viral political climate as a single continuum. The 30 essays, poems, stories, and novel excerpts record a progression of events and emotional states: from Corona’s emergence in January 2020 to everything it’s revealed to us since then—having thrown a spotlight on fault lines here and abroad in a starker way than ever before. The following text is my introduction to Writing the Virus, written at the end of August 2020, when we didn’t yet know what the outcome of the US presidential election would be. It takes stock of the situation at a particular period of time in both Germany and the United States and introduces the anthology’s individual sections.

Writing the Virus

The 31 authors of StatORec’s “Corona Issue,” published in our online magazine from mid-April to September 2020, explore the experience of lockdown, quarantine, social distancing, and the politicization of the virus from a wide variety of perspectives. As an online literary journal with staff based in Berlin and Brooklyn, our purview is circumscribed by our experiences in the United States and in Germany even as we look beyond to the global perspective. As of today, August 29, 2020, we’ve been living with SARS-CoV-2, the novel Coronavirus, for eight months. Countries that quickly adopted strict, coordinated measures to contain the outbreak saw far fewer infections and deaths than countries whose leaders pursued political strategies of misinformation and denial. And yet here in Germany, whose population has undeniably benefited from good governance, today is also the day that a second “anti-Corona” rally is taking place in the country’s capital.

Covid affects people in vastly different ways; it affects nations in vastly different ways. The pandemic seems to have brought every country’s worst nightmare back to life. In the United States, the racially motivated violence we’ve witnessed recently on the part of the police and of white supremacists feels like a resurgence of our original sin, of whatever allowed us to found a nation based on slave labor, while Germany, known for its rational leadership and admired as a shining example of a fully functioning democracy, is currently seeing a reemergence of the dark fanaticism of its fascist past. A volatile mix of the radical right and esoteric-minded, of Coronavirus deniers, conspiracy theorists, Reichsbürger, neo-Nazis, and anti-vaxxers are calling on protestors to “storm Berlin”—spurred on by a group that goes by the name “Querdenker 711” (Lateral Thinkers 711) and calls for the immediate overthrow of the German government and imprisonment of Angela Merkel; the far-right political party Alternative for Germany (AfD), which is exploiting the opportunity to maneuver the movement to its own ends; and other right-wing influencers who see the public health measures as an attack on their personal freedom. Earlier this week, the city’s interior minister banned the demonstration, citing grievous infractions of public safety regulations during the first anti-Corona protest on August 1, which deliberately defied mask-wearing and social distancing requirements, conflating them with a nefarious plan on the part of the state to strip its citizens of their basic rights. But at 3 a.m. this morning, the administrative appeals court of Berlin-Brandenburg lifted the ban, and while many have expressed dismay at the prospect of another super-spreader event in the capital, the takeaway is that banning the protest and citizens’ right to freedom of assembly will only serve to fuel the movement’s supporters. And so, the anti-Corona rally, which is expected to attract more than 20,000 demonstrators from all over the country, will go ahead as planned. With one difference: this time around, calls for violence have been spreading through social media, with far-right supporters advising people to come armed and ready to fight.

Are American Coronavirus deniers comparable to their German counterparts? In Europe, as in the United States and elsewhere, denying the existence of a global pandemic and defying basic measures to contain it can seem like a kamikaze mission, a form of collective insanity. Do they really believe that Bill Gates is conniving with other Illuminati to install a pharma-dictated technocracy to exert mind-control through a legally mandated vaccine? Surely there’s another explanation, another set of doubts and grievances fueling the movement. Germany has seen a resurgence of the highly charged phrase “Lügenpresse”—the “lying press,” an older, German version of “fake news” that originated during WWI to counter enemy propaganda and that infamously resurfaced during the Nazi era and again later, as a reactionary anti-immigrant movement rose up in Germany in 2014. We live in volatile times on both sides of the Atlantic; large parts of the population are becoming more polarized than ever before. And yet a dangerous divide has opened up between the measures mandated to contain contagion—the closure of schools, universities, daycare centers, and almost everything else that enables us to live the lives we’ve known until now—and the ruination of livelihoods and abrupt rise in bankruptcies, foreclosures, homelessness, mental illness, and domestic abuse. Some of the restrictions can seem unfair, while the official reasoning offered to justify them comes across as inconsistent at best. In Germany, theaters and cinemas are allowed to open at reduced capacity and under strict distancing measures, while airlines, evidently the more powerful lobby, continue to pack passengers into every available seat. The restrictions seem at least partly based on economic dictates—culture is clearly less important than the aviation industry or the automobile industry. So are we being lied to?

In the first days of lockdown, a solemn mood prevailed as we watched health workers battle an invisible enemy under inconceivable conditions. Overwhelmed by the sick and dying and forced to adopt triage measures otherwise implemented during wartime to distribute a limited number of ventilators to a far greater number of patients in dire need of them, we wept with doctors and nurses online, their faces bruised by countless hours of wearing PPE, as they described the unbearable reality they were facing. As a new sense of solidarity took hold, we adhered to lockdown and quarantine, we scrubbed our hands and applauded essential workers every evening from our windows and balconies. And as anxiety gave way to an appreciation for the respite the virus was offering some of us, a temporary pause in the ever-accelerating speed of modern life, a new feeling emerged: that the virus’s appearance, in spite of all its perils and in spite of all the sacrifices required of us, harbored unprecedented potential. Some said that nature was telling us to slow down; that nature was giving humanity a chance to wake up and finally comprehend the urgent need for change. As the first lockdowns were eased, we watched citizens of countries with large tourism industries retake their streets, and in spite of the economic blow dealt to so many, the images of children playing in piazzas normally packed with foreign crowds seemed, at least to those of us enjoying the comparable luxury of home office, to carry a promise of some kind: a return to a more sane and humane way of living. This state of grace was short-lived, of course; the loss of livelihoods and the collapse of entire economic sectors would soon accelerate a backlash during the course of which a degree of risk and potential contagion would become normalized. Human lives are not, as we’re frequently told, merely lost to a dangerous virus, but to broken economies and financial ruin.

But it’s hard to ignore the feeling of a lost chance. After years of watching the world’s governments fail to work together to bring about the necessary transition from carbon fuel to green energy alternatives; after scientific studies repeatedly revealed that reducing carbon emissions at such a late stage would at best alleviate only a small part of the inevitable devastating effects of global warming, but that this was far preferable to doing nothing and unleashing the worst-case scenario on the world’s most vulnerable communities; after watching politicians offer lip service at climate conferences as the status quo remained largely unchanged—suddenly, everything seemed possible after all: industrialized countries were, indeed, rich enough to subsidize entire sections of the population as the skies turned a blue we hadn’t seen since the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, which ten years ago had also brought international air travel to a standstill. It turns out that we can, in fact, reduce emissions; we can, in fact, slow down production. Why was the virus able to achieve this, while the prospect of an uninhabitable planet was not?

The majority of the texts in StatORec’s “Corona Issue” were written exclusively for the magazine. We reached out to authors we knew and admired, and in some cases asked them to write on specific themes. A sense of urgency prevailed throughout, a knowledge that we were chronicling something, responding to something we’d never experienced before—something that was changing us and the social fabric all around us in ways that we would need time to fully understand. Each of these works responds to the present tense, each shares a sense of vibrating immediacy. For this anthology, we’ve organized the 31 stories, essays, poems, novel excerpts, and flash fiction into six categories: “Chronicling the Pandemic,” composed of essays, among them a harrowing account of contracting and surviving Covid-19, that track events over a particular period of time and range from the virus’s first appearance in early 2020 to the weeks and months of uncertainty that followed; “The Anxiety of Distance,” which brings together pieces that capture the strange psychological space of isolation and social distancing; “Writing Against the Virus,” a group of works in which the very meaning and purpose of writing comes under scrutiny in the context of a larger crisis; “To Covid, with Love,” comprised of essays and an excerpt from a novel-in-progress in which the overriding response to the global pandemic is a renewed focus on personal relationships, caretaking, and love; “Invisible Danger,” in which a sense of fear and even paranoia over an essentially unknowable enemy prevails; and “The Fallout,” a collection of essay and poems that explicitly address the socio-political implications and after-effects of the pandemic. While each of these works could easily inhabit several categories, we’ve looked to their underlying mood, an atmosphere that lingers beyond the ideas, facts, and events they describe. The sections themselves—which track the progression from epidemiological threat to the political crisis the virus soon became—sketch out the evolution of Corona’s rapidly changing meaning over the past half year. It’s our belief that these pieces of writing, composed in unusual times and under considerable pressure, will endure as documents of a particular period of history, testimonies to states of mind we will quite possibly have forgotten as we turn our attention to the new challenges facing us.

As far as Berlin and its anti-Corona movement goes: an estimated 50,000 people took part in the demonstration, more than twice the original estimate; the police barely managed to prevent a horde of neo-Nazis and other right-wing extremists from (literally) storming the Reichstag; and Germany has escaped—for now—a Corona-induced uprising. But at this point in time, while the danger of civil unrest in the upcoming US presidential election season and its aftermath remains a troubling prospect, the effect American instability will inevitably exert on the rest of the world will carry repercussions currently difficult to predict.

Andrea Scrima

Editor-in-chief, StatORec

Writing the Virus: Order the book at Outpost19 Books or on Amazon.

You can also visit our YouTube channel to see a selection of readings from November 2020.