by John Hartley

“To err is human,” observed the poet, Alexander Pope. Yet, why do we consciously choose to err from right action against our better judgement? Anyone who has tried to follow a diet or maintain a strict exercise regime will understand what can sometimes feel like an inner battle. Yet why do we stray from virtue, choosing paths we know will lead to inevitable suffering? Force of habit? Addiction? Weakness of will?

This crisis of moral choice lies at the heart of Western philosophy, as the Ancients crafted their doctrines to explain why individuals often fail to realize their good intentions. “For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out.” Observed St Paul, “For what I do is not the good I want to do; no, the evil I do not want to do–this I keep on doing.”

Akrasia in ancient thought

Homer’s Iliad paints a poignant portrait of humanity, ensnared in a cycle of necessity. This relentless loop can only be broken by wisdom and self-knowledge, encapsulated in the Delphic maxim “know thyself.” Socrates, however, argued that true knowledge of the good naturally precludes evil actions (If you really know what is right you will not do wrong!) He contends that misdeeds arise not from a willful defiance of the good but from flawed moral judgment—a tragic aberration, mistaking evil for good in the heat of the moment.

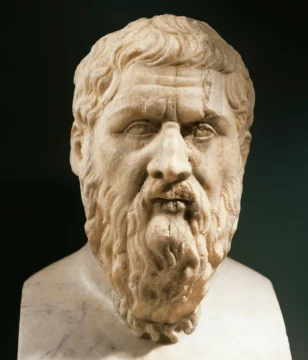

Plato linked wisdom and necessity to the duality of good and evil. He envisions self-realization and ordered integration as pathways to the good (inefficiency and unrealized potential signify malevolence). For Plato, good and evil are not external forces but internal currents: one flowing with love and altruism, the other emanating greed, envy, and malice.

The ascent to goodness, according to Plato, hinges on self-mastery and moral transformation, guiding one’s life towards the ideal form of goodness. Stoicism, of course, has experienced something of a resurgence of late, owing to Gen Z influences advocating extreme self discipline and heightened personal responsibility. Read more »

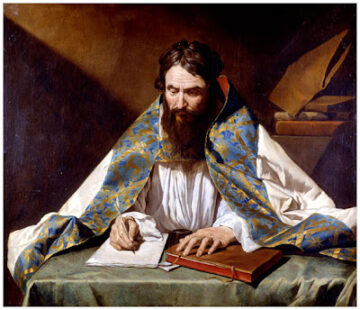

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”