by Daniel Gauss

Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony helps explain how the power structure of modern liberal-democratic societies maintains authority without relying on overt force. Many definitions of hegemony point out that it creates “common sense,” the assumptions a society accepts as natural and right.

Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony helps explain how the power structure of modern liberal-democratic societies maintains authority without relying on overt force. Many definitions of hegemony point out that it creates “common sense,” the assumptions a society accepts as natural and right.

It works by getting inside our heads and convincing us of concepts that would not hold up under rigorous investigation. Our criminal justice system is built on such taken-for-granted principles, many of which go unchallenged despite producing deeply inhumane consequences.

Crime, for example, is assumed to be a personal “moral failing” rather than a systemic problem. Why some people (mostly poor and marginalized) fail morally is not understood or explained. Instead of understanding crime as a product of poverty, racial segregation, inequality and limited opportunity, our system treats it as evidence of bad individual character or individual moral flaws, basically recycling old theological ideas while ignoring more than a century of psychology and sociology.

The judicial system still draws from an outdated worldview, uninformed by social science, that assumes the validity of an unquestioned social hierarchy, based on inequality of opportunity, and shifts responsibility onto individuals who are often living in trying and corrosive conditions. This amounts to a form of blaming the victim instead of accepting social and economic responsibility for others. Read more »

Resmaa Menakem’s

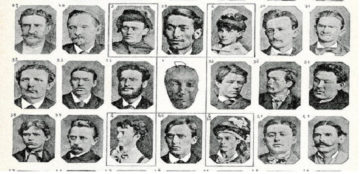

Resmaa Menakem’s  When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”  White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (