by Michael Liss

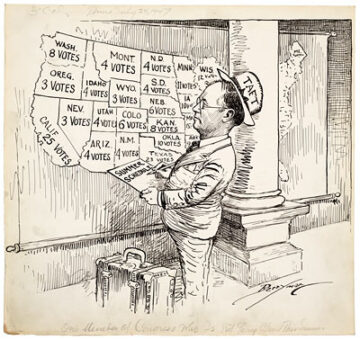

The optimistic yet somewhat dyspeptic-looking gentleman to your right (quite appropriately to your right) is Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft, a/k/a “Mr. Republican.” Senator Taft was the son of former President and Chief Justice William Howard Taft, a devoted former member of Herbert Hoover’s staff, and an Isolationist who hinted that FDR had encouraged the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor as a way of inducing America to enter the war against Germany. He was also a fervent proponent of small government and big business, opposed expansion of the New Deal, and in 1947, helped override a Truman veto of the thoroughly anti-Labor Taft-Hartley Act.

In short, Mr. Republican was the real deal. In a 2020 essay for the Heritage Foundation, the conservative historian Lee Edwards wrote:

Before there was Ronald Reagan, there was Barry Goldwater, and before there was Barry Goldwater, there was Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio. From 1938 until his unexpected death in 1953, Taft led the conservative Republican resistance to liberal Democrats and their big-government philosophy.

The man could have been President. He certainly tried—running for the GOP nomination in 1940, 1948, and 1952—and, although he fell short, he inspired a generation of limited-government conservatives and left his name “Taft Republicans” to posterity. Taft, and Taft Republicans, are a starting point for what is called “Movement Conservatism.”

Beginning in the early 1950s, their ideas were adopted, co-opted, and expanded upon, perhaps most notably by the young William F. Buckley, Jr. and his National Review. Buckley and other Movement Conservatives went beyond issues like small government and anti-Communism. They explicitly rejected Abraham Lincoln’s vision that America was “dedicated to the principle that all men are created equal” and instead insisted that the Founders’ core value was the protection of private property. The role of government was to get out of the way—except when advancing the interests of the owners of private property.

1952 was a very Republican year, and it looked as if it could have been Taft’s year. The public was ready for change, and the Party seemed ready as well. The moderate wing was spent. Thomas Dewey had lost in the general election twice, including a very winnable race to Truman in 1948. It was time for something new (or something old), and Taft was an obvious choice. His misfortune was the availability of Dwight Eisenhower, who (finally) came off the fence and declared himself a Republican. At the Convention, the Taft people put up a fight, but Ike won on the first ballot after some delegates switched their votes. Taft couldn’t escape a deadly math: after being out of power for two decades, there was a hunger among Republicans for winning, and Ike was the most popular man in America.

Eisenhower’s Presidency was a bit of a disappointment to Republican conservatives. He didn’t object to giving them occasional policy or appointment wins, but he ran a different type of Presidency, more activist, more internationalist, more willing to use government on behalf of ordinary people, including minorities.

Where did this leave Movement Conservatism? In a frustrated, but still healthy state, because there were Movement Conservatives in the Democratic Party who were growing restless. Southern Democrats had tried the Dixiecrat experiment in 1948 but had failed to win enough states to prevent a Truman win. Ike offered them cold comfort policy-wise: his choice for Chief Justice had authored Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and he was sending federal troops in to enforce desegregation. Southern Democrats had always been reliable conservative legislative votes, but also reliable Democratic votes in elections. They weren’t quite ready to switch parties, but Movement Conservatism, which was deeply unfriendly to Civil Rights, was happy to welcome them. LBJ’s role in the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 helped build the next leg of the Movement Conservative Stool. The vote, and LBJ’s advocacy for it, angered conservatives everywhere and almost certainly aided the nomination of Barry Goldwater in 1964, who crushed the liberal Nelson Rockefeller candidacy. The general election was different—Goldwater was considered a radical in many quarters, and LBJ won in a landslide. Nonetheless, in addition to Goldwater’s home state of Arizona, the Movement Conservative took Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Arkansas—from Texan LBJ.

The South had found themselves a hero—actually, two, the second being Ronald Reagan, who gave Goldwater an endorsement in an extraordinary speech, “A Time For Choosing.” Sixteen years later, Reagan himself swept the South, except for Jimmy Carter’s home state of Georgia. The 1980 Reagan candidacy did one other thing that impacted Movement Conservatism—Reagan and his team found a way to meld Republicans’ traditional business support (which often was carefully agnostic when it came to social issues) with a newly emergent and potent Religious Right, which was then in the process of organizing to obtain secular power alongside the spiritual.

Reagan’s construct worked, and it continues to work to this day. Business got what it wanted—tax cuts, regulatory rollbacks, and challenges to organized labor. Social Conservatives got what they wanted—pro-church and pro-life policies, and influential places at the table for faith-based organizations. Both shared in the huge prize, conservative Supreme Court Justices with a contempt for precedents and hunger to impose their personal views on the rest of the country. Reagan’s two terms were a paradise, and George Herbert Walker Bush’s term yielded the prize of prizes—Clarence Thomas to replace Thurgood Marshall.

It looked like it would never end, wins evoking a gauzy past of men of rectitude leading a thrifty, pious flock. The historian Heather C. Richardson talks about the cowboy image in politics, and, first in Goldwater and then, powerfully, in Ronald Reagan, Movement Conservatives found their cowboys. Reagan, in turn, energized a new cadre of conservatives who entered politics at the state and Congressional levels, delivering more success. But Bush I wasn’t nearly as charismatic as Reagan, and Movement Conservatives fumed their way through the Clinton years: How was it possible that Americans didn’t reject this voluble libertine? They got their mojo back when folksy Texan George W. Bush squeaked past the stiff technocrat Al Gore and used razor-thin margins in Congress to start a couple of wars, expand the security state, and begin chopping away at things that conservatives didn’t like. The election, and then reelection, of Barack Obama confounded and infuriated Movement Conservatives. The post-mortems after Romney’s loss in 2012 all pointed toward creating a more open party—more tolerant, more diverse—and were contemptuously tossed aside. The Movement Men knew better: McCain and Romney were just not conservatives. Movement Men also had the reins of power: Win or lose, primary after primary, election after election, the GOP continued its rightward march.

Movement Conservatism provided an identity and a set of beliefs, and it created a pathway for ambitious Republicans to rise in the ranks, but does it retain intellectual vitality? As an intellectual construct, it is deeply flawed. Movement Conservatives claim to be walking in the footsteps of the Founders—and, more than that, redeeming the Founders’ vision of the nation. In their view, very limited government, strong support of business, a hostility to Labor, the end of many social programs (even those as embedded as New Deal Era ones like Social Security), the elimination of Civil Rights (or its inversion, the claim that white men are the imperiled group), the imposition of religion-based social policies, and the conviction that the country should be run by its (male) elites in a top-down manner are at the end of an unbroken chain from James Madison himself.

Full stop here. Yes, that hyperbolic statement above approaches the reality of the Founders’ world. Half of them were slaveowners (as were six of the first seven Presidents). Madison’s structure of government insulated some of the decisions of the elites from the common man. The franchise was far from universal. Rights were more often defined by their limitations then their presence. The Founders wrote and ratified what they believed in, or, at the very least, what they could accept. The elites decided, and would continue to decide, even though they were still loosely answerable to the common citizen. Yet, with all that, the Constitution was still a great leap forward in the cause of freedom.

The 21st Century is not the 18th, and our world has changed. We now vote directly for our Senators, thanks to the 17th Amendment. Prior to that, State Legislatures picked them. From 1812 to 1824, Louisiana Electors were also selected by the State Legislature, and not by direct vote. Theoretically, the passage of 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments removed the legal barriers for Blacks to participate in civil society and to vote, and the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act put some teeth in. As to women, it still boggles my mind that my immigrant grandmother was an adult naturalized citizen for several years before she was able to vote. She then continued to do so for every election over the next 70 or so years, considering it both a civic duty and a privilege.

The Founders would likely be shocked, but it was the structures they put in place, including a method for Constitutional amendment, that enabled those changes. They were too intelligent and far-sighted to have failed to realize that the future might have a bolder, more expansive vision than theirs, and they created the tools to enable that vision.

That bothers many people, particularly Movement Conservatives. It undercuts a key argument for them, that the rest of society is wrong and they are right, that they are the only ones fit to govern because they possess a greater degree of civic and personal virtue. William F. Buckley cast them in heroic terms when he said, “A conservative is someone who stands athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it.” What he also meant was, “I want to preserve the power structure because I am a key player in it.”

That entitlement to power is what is on trial in this November’s election. Republicans will nominate, for the third time, a man who exposes them with the sheer brashness of his grasp. In October 2016, less than four weeks before the election, Rod Dreher, an uber-conservative who has subsequently moved to Budapest to enjoy the freedoms bestowed by Viktor Orban’s form of democracy, had this to say in The American Conservative: “The moral collapse of Movement Conservatism is nearly complete.”

What was Dreher then reacting to? The quickness to defend Donald Trump for his “grabbing them by the p—” remarks, a defense that rapidly stretched across the GOP coalition and included many prominent faith leaders. Does he still feel this way? Feel free to check out Rod Dreher’s Diary on Substack for his current take on American politics and the respective virtues of Republicans and Democrats.

I’m not going to be too hard on Dreher, because, nearly eight years later, the web that held Trump aloft seems even stronger today. A salesman his whole life, a top-tier burnisher of his own brand, a ruthless negotiator, Trump understands better than anyone what motivates people—and that virtually everyone has a price. He possesses the Republican Party, possesses Movement Conservatism, and possesses virtually every Republican politician who wants to keep his or her job. They come to lower Manhattan to show their support for him in a trial involving a payoff to a porno star. What must they be thinking? Somewhere under those matching blue suits, white shirts and red ties, there must be some sense of shame, but, as Henry Kissinger once said, “Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac.” Trump giveth, and Trump can taketh away. November will tell us (and them) how much he can giveth and how much he can taketh away.

What happens next? Many years ago, I worked on political surveys, and, as a public service, I’m going to apply those skills here. I talked to two of my closest friends. Yes, I hear the doubters: small sample size, socio-economic sorting and self-selection, question wording, question order, how the crosstabs would look, and whether I’m ready to take on giants like The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Fox. Still, I’m all for the underdog, and since I’m the underdog here, I say this one-question poll works: “What do you care about?”

Friend One: “1) Democracy, 2) Democracy, 3) Democracy, 4) World peace (NATO, the Middle East, Ukraine, Russia, China), 5) Economics (‘middle-class” jobs, taxes, inflation, Social Security, student debt’).”

Friend Two: “Crime, Fiscal responsibility/deficit. Border.”

Smart Friends, right? Smart me for having smart friends who occupy different spaces on the political spectrum. Since the readers of 3 Quarks Daily are also quite smart, I’m sure they’ve noticed the obvious: The two combined lists are not all-inclusive, and they shouldn’t be. For one thing, my two friends are both white males, which may impact their views. What they are doing is something we all do: we sort issues by personal priorities—in the here and now, what needs attention, and when? Urgency drives people to the polls. Hypothetical issues, at least hypothetical in the moment, tend to fit into a packet of likes and dislikes that are less “inspirational” and can be dealt with later. Politics is a marketplace of ideas, but urgency is the proxy for demand—that’s why the voter comes, pockets filled with currency (vote, volunteerism, cash). Soon enough, it will be time to choose.

William Howard Taft, Robert’s Dad, once said, “Too many people don’t care what happens so long as it doesn’t happen to them.”

Be among those who care.