by Akim Reinhardt

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (mostly over 50, conservative, and/or Republican) bitter about the supposedly undue attention, sympathy, and “breaks” that minorities receive; who insist actual racism was a problem only in the past, because Civil Rights “fixed” it; who believe anyone complaining about racism is just looking for an unfair edge in America’s level, color-blind playing field; who decry so-called “reverse racism”; who actually believe it is harder to be white in America than to be black or brown; or who simply minimize and downplay the existence racism.

White Americans get a lot of things wrong about race. And not just the relatively small number of blatant white supremacists, or the many millions (mostly over 50, conservative, and/or Republican) bitter about the supposedly undue attention, sympathy, and “breaks” that minorities receive; who insist actual racism was a problem only in the past, because Civil Rights “fixed” it; who believe anyone complaining about racism is just looking for an unfair edge in America’s level, color-blind playing field; who decry so-called “reverse racism”; who actually believe it is harder to be white in America than to be black or brown; or who simply minimize and downplay the existence racism.

Not just them. Even the small majority of whites who recognize that race remains a big problem in America often get it wrong. For example, many (most?) of them think that race is primarily about black and brown people. It’s not. Racism is primarily about white people.

Minorities suffer the effects of racism, and we must acknowledge and work to end that; however, you cannot cure an infection by simply placing a band-aid over the sore. You must clean out the wound thoroughly, surgically if need be, disinfect it, and then attack the infection at its root with antibiotics. In the old days it might have meant cutting off an appendage or limb. Similarly, racism won’t end or even be substantially reduced by strictly focusing on the suffering of its victims and making amends. Those are important and necessary first steps, but they don’t get at the core of the problem. Minority suffering is racism’s result, but racism is caused by what white people think and do.

White people empathizing with black and brown people is important, and it is vitally important that whites listen to minority voices. However, ending or substantially reducing racism will not come about until white people talk to each other and sort themselves out. Because racism is a white problem.

As Europeans invaded the Americas and built up the African slave trade, they moved beyond standard religious bigotry and ethnic rivalry and invented various pseudoscientific concepts of race. Since then, white people have embraced and applied those ideas to the world’s non-European descended populace. That is the fundamental truth of race and racism. Minorities have done an amazing job of confronting, grappling with, and overcoming racism, but they cannot actually end racism. Just as someone who has had something stolen from them cannot stop the burglars from burgling. Only thieves can decide to not steal anymore. Only white people can put an end to white racism. Racism doesn’t end when black and brown people change. It ends when white people change.

Thus, the common assumption that racism will finally end when white people improve their relations with minorities, is backwards. Improved racial relations is a sign of declining racism, not a cause of it.

The need to attack racism at its source, and to work earnestly towards its eventual extinction, has increased urgency in this Age of Trump. Donald Trump’s recent dismissal from the presidency not withstanding, we are still swimming in a sea of Trumpism (with related manifestations appearing around the world), and perhaps its strongest tide in America is the undertow of white racism. Trumpism emboldens society’s most overt racists to act violently, and more pedestrian racists by the millions to freely voice their antipathies and cast wide nets of blame and resentment. All in all, racist white Americans are more confident than they have been in a long time, and more willing to push back hard against the slow march towards equality. Which means white America should stand up to itself. White people need to confront and address white America’s race problem. It’s time for White America to clean house.

From its founding, white-dominated culture in the United States accepted racism as de rigeur. There were minor guardrails, such as standards of polite conversation, various debates, and even war about racial policies (eg. slavery), but racism itself was never seriously challenged until the modern civil rights movement. Indeed, most 19th century opponents of slavery were virulently racist, criticizing the institution on economic, not humanitarian grounds. And even the most sympathetic abolitionists often took for granted supposed black inferiority. But all that finally began to change in the decades following WWII.

High school history classes often focus on the civil rights movements’ legal and political achievements such as Brown v. Board of Ed. (1954), the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965, and the ultimate dismantling of Jim Crow apartheid. These gains were and remain vitally important; America’s ongoing informal segregation and ongoing Republican efforts to suppress black voting remind us of that. But there’s another central achievement of the Civil Rights movements, and the subsequent power movements (eg. Black Power, Red Power, La Raza) that is often overlooked: the shift in American cultural attitudes towards racism. Specifically, during the 1970s a popular culture consensus emerged about racism: It’s bad.

Beginning in the 1960s, African Amreican, Latino, Native American, and Asian American civil rights protestors expressed not only their opposition to oppression and bigotry, but their humanity, their pride, and their unwillingness to accept second class social standing. By the 1970s, much of white America had made some degree of peace with this by accepting the bare minimum: acknowledging that racism is scientifically wrong and morally repugnant.

But there has always been a push back against that change. And it is a 21st century version of this push back that Trumpism has celebrated and elevated.

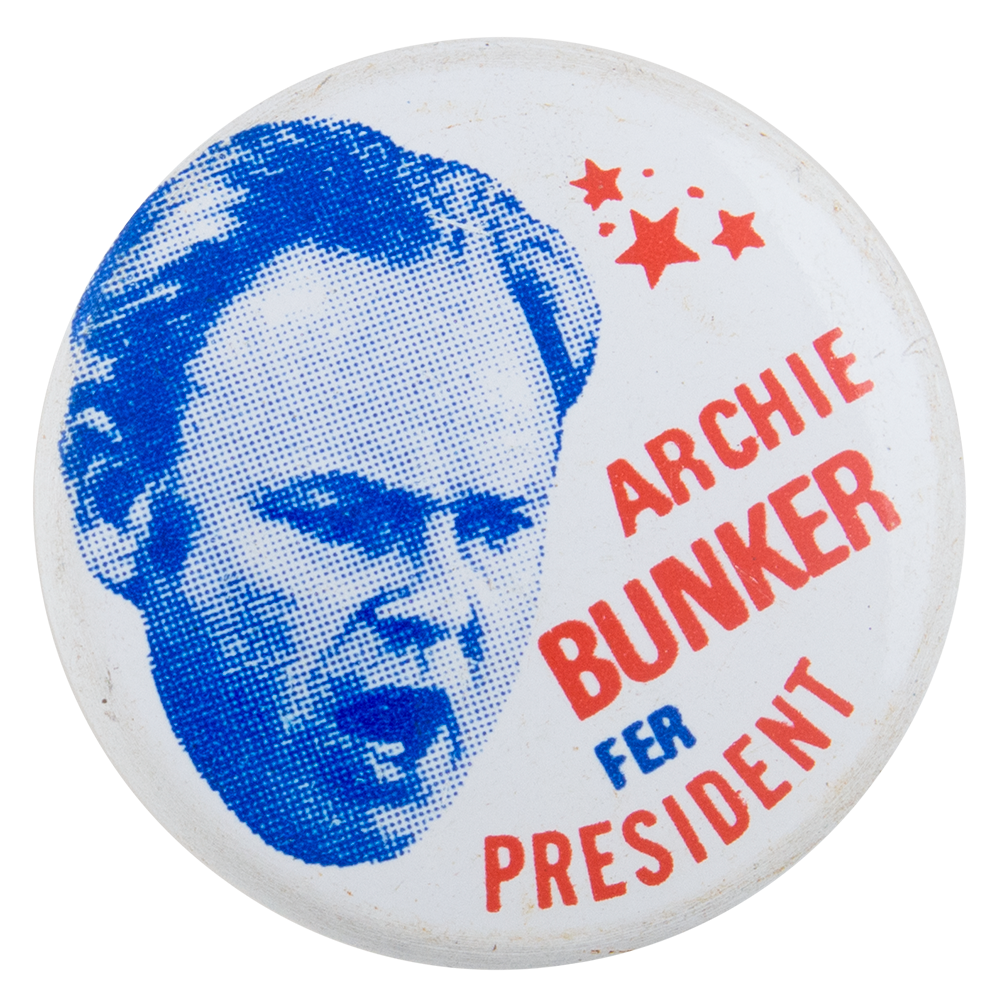

An early satire of that push back came in the form of Archie Bunker, lead character in the 1970s sitcom All in the Family. Debuting in 1971, Archie did not adapt well to the changing times. He was openly and unapologetically racist, sexist, and homophobic. He was also perpetually grumpy despite all the advantages that came with white, heterosexual masculinity in mid-century America. He was the patriarch of his family and respected in the community. With little formal education he still held a good paying blue collar (probably union) job, and owned a middle class home in Queens, one large enough to comfortably house himself and his wife, daughter and son-in-law. Yet he forever saw himself as the victim, pine for a halcyon past, and raged at how wrong everything was going.

Archie’s reactionary views were often the butt of the show’s jokes, but the scripts and Carroll O’Connor’s performance developed and humanized the character. Archie had emotional depth. Despite his flaws, and sometimes because of them, he was relatable, and at times even sympathetic.

But you don’t find the kind of success that All in the Family earned without drawing the widest possible audience. In a pre-cable era of just three networks, it was the most watched show in America from 1971 – 1976, and a top 10 show for almost all of its decade on television. Back when the U.S. population was only two-thirds its current size, the typical episode of All in the Family was watched by about 20 million people.

In other words, not just by blacks and anti-racist whites.

Because the show was so well made and O’Connor’s performance so iconic, racist white Americans easily identified with him instead of feeling lampooned by him. The character intended to be a satirical critique on racism (and sexism) was unironically embraced by many racists (and sexists).

This reflected a wider discontent in white America. Tens of millions of white Americans resented ongoing challenges to racism, even as they learned not to admit to anyone, or even themselves, that they were actually racist. Because racism was now bad. Yet racist they were, and that racism needed an acceptable outlet beyond the catharsis of a TV sitcom.

In the aftermath of the Democratic Party’s division over civil rights, the Republican Party fashioned itself the political home of racial resentment. Nixonians first took advantage by developing a Southern Strategy for the 1972 presidential election: enticing white Southern voters resentful over the changes wrought by civil rights, luring them to join the GOP, or at least punish or abandon the Democratic Party whenever it seemed to be “siding” with minorities. During the 1980s, Reaganites consecrated this dog whistle approach to racial politics with coded language about affirmative action, dangerous cities, and welfare queens, making racial resentment an acceptable approach for establishment Republicans across the nation.

After two decades of devastating defeats in national elections, the Democratic party responded by moving rightward, limiting its liberal agenda to a handful of issues (mostly abortion rights and gun control), and largely abandoning its commitment to combating racism. Indeed, it was the Democratic Party as much as the GOP that spearheaded or supported policies such as welfare reform, the war on drugs, and mass incarceration, all of which disproportionally harmed minority communities.

By the 21st century, the politics of racial resentment was so entrenched in white America that when a half-white man raised in, among other places, Kansas, was elected president, it led to an enormous racist backlash because his immigrant father, whom he barely knew, was black.

By the 21st century, the politics of racial resentment was so entrenched in white America that when a half-white man raised in, among other places, Kansas, was elected president, it led to an enormous racist backlash because his immigrant father, whom he barely knew, was black.

The Obama backlash was immediate, profound, and steeped in the politics of racial resentment. Right Wing media attacks were consistently seething, often cloaked in lies, and occasionally unhinged, as evidenced by the utterly ludicrous but phenomenally popular birtherism conspiracy. During the 2008 campaign, one-third of Republican voters believed Obama was from Kenya. The following year, less than half or Republicans believed he was born in the United States. Lunacy, fed by racial resentment, had thoroughly infected the GOP, and the party’s own politicians eagerly cashed in on it.

The long list of prominent politicians who peddled these racist lies included: Sen. Richard Shelby, Sen. David Vittar, Gov./VP candidate Sarah Palin, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, form governor and presidential candidate Mike Huckabee, Rep. (and current senator) Roy Blunt, Rep. Michele Bachmann, Sheriff Joe Arpaio, and Judge/Sen. candidate Roy Moore.

Oh, and then there was the reality TV celebrity who pushed that conspiracy from the start and continues to indulge in it even to this day: Donald Joseph Trump.

Trumpism gave full throat to racist resentments that had been rumbling through white America ever since civil rights, and had found a political home in the GOP. This is why so many millions either cheered or at least tacitly accepted Trump’s labeling of Mexicans as rapists and murders; his fantastical warnings about the U.S. border being overrun with brown gangsters; his calling African countries “shit holes”; his attempt to ban Muslim immigrants; his lies about New Jersey Arabs celebrating 9-11; his claim that a federal judge was biased because of “his Mexican heritage”; his lie that 81% of white murder victims are killed by blacks (it’s actually 15%); his comment that all Haitians have AIDS; his comment that Nigerians visiting America “would never go back to their huts”; his claim that Puerto Ricans suffering after Hurricane Maria are lazy and “want everything done for them”; his assertion that Colin Kaepernick should leave America; his endlessly calling Elizabeth Warren “Pocahontas”; his support of Confederate symbols and celebrations; and on and on and on and on.

Trump could never have gotten elected if not for white America’s post-civil rights racial resentments. Indeed, they more than anything else may have gotten elected. And while Trump is no longer president, our society remains shot through with the longstanding racism that he capitalized on and promoted.

It is now long past time that white Americans who really do oppose racism standup to those white people who do not, to those white people who deny racism still exists, make excuses for it, or claim it’s not that bad. It is time to call out fellow white people who cannot do the bare minimum of recognizing reality.

White Americans need to stare themselves in the mirror, both as individuals and as a group. Instead of insisting they are not racist, white Americans need to have uncomfortable but necessary conversations with each other about the racism we promote or just plain tolerate. We can no longer believe we’ve done our part simply because we nod our heads and agree that racism is bad. It is no longer enough to condemn only the most blatant expressions of racism, such as Derek Chauvin murdering George Floyd or torch-bearing Klansmen screaming about “niggers.”

It’s time white Americans, as many of them who are willing to, come together and actively work to end racism. Because ending racism is on us.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com