by Michael Liss

We had reached a place in Virginia. It was a very hot day. In this jungle, there was a man, a very tall man. He had with him his wife and several small children. We invited them over to have something to eat with us, and they refused. Then I brought something over to them on an old pie plate. They still refused. It was the husband who told me he didn’t care for anything to eat. But see, the baby was crying from hunger. —Jim Sheridan, Bonus Marcher, quoted in Studs Terkel’s Hard Times

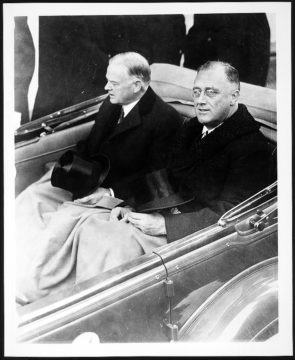

There is a mood, a color, to the Great Depression. It’s a shade of gray, sooty and ominous, without sun, almost without hope. Wherever its victims stopped—on city streets and farms, on a muster line or on one for bread, outside tents or structures made of bits and pieces of packing boxes and cardboard, on trussed-up jalopies headed West, or on boxcars with hoboes like Jim Sheridan—there were chroniclers of images and words, all gray. Gray and ominous as well were the faces of those who were leaders in business and politics. Dark suits, white shirts, muted ties, emitting seriousness of purpose, and consciousness of class. Those men were Authorities—vested with power, but often remote from those who would be impacted by their actions, or non-action. They shared with their peers a fervent belief in their own self-worth, earned through moral superiority.

Herbert Hoover was in this second group. He had fought for and secured it through intensely hard work and great talent. He was the “Great Engineer,” the perfect man to be heir to a pro-business philosophy that had, in the Harding-Coolidge years, brought abundance. His landslide victory in November 1928 promised more of the same—more jobs, more innovation, more wealth, an appreciably raised standard of living, and the possibility of moving up in class, as he had. A better statesman for Capitalism, for the American Dream, for the American Promise was hard to imagine.

It blew up, of course, most spectacularly in the stock-market crash, but also as a result of secular forces both in the United States and abroad that made seemingly healthy economies reel. That these problems pre-dated Hoover’s taking office did not grant absolution for their existence. You don’t get a honeymoon in a crisis. Nor did successive governments in other Western countries get one. Democracy tottered because its stewards seemed inadequate to the task. Should they continue to prove to be inadequate, then more authoritarian forms of government might be the answer. Italy was already under the fist of Mussolini, Japan was eyeing China as a resource-filled morsel, and Germany was considering an angry man with a funny mustache who seemed a bit bellicose, but maybe could put people back to work.

What of the United States? In what direction would it go? Read more »

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”